South Africa

ANC Policy Conference 2017: Foreign relations content of Gwede Mantashe’s report gives pause for concern

Was Gwede Mantashe in his diagnostic report deliberately cloaking himself in ultra-orthodox, more-anti-imperialist-than-thou, ANC foreign policy ideological rhetoric in order to protect his left flank against attack by the Jacob Zuma/Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma camp while he rebuked it for using the regime change narrative as a diversion from state capture, asks PETER FABRICIUS.

South Africa’s foreign policy could be characterised as ANC paranoia, refracted through the lens of reality. The final picture is often not a pretty sight. But it’s usually a lot prettier than the original, unrefracted image.

Take, for instance, the controversial Diagnostic Organisational Report, presented to the National Policy Conference on its opening day, Friday, by ANC Secretary-General Gwede Mantashe.

It was the frank acknowledgement in this report that state capture by Zuma’s cronies, the Guptas, is badly hurting the ANC’s 2019 election prospects which garnered the most attention, especially when the Zuma camp tried – and failed – to have it suppressed.

The foreign relations content of this report has been largely ignored, perhaps mercifully so. It was a brief discourse on the threat to South Africa and like-minded “progressive” countries of “the colour revolution”….. an “offensive from external forces, with the regime change agenda at its core…”

Mantashe cites, as examples of the Colour Revolution, the Rose Revolution in Georgia, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan, Arab Spring in North African Countries and the hybrid revolution in Syria and Yemen.

“The colour revolution is the mode of the offensive, possibly graduating the offensive into a hybrid combining soft and hard forms of the attack, with the potential to return southern Africa into its Cold War era of conflict.”

At a later press conference Mantashe refused to identify the specific Western countries which were pursuing the regime change agenda but referred to a report that had been written by former southern African liberation movements – now governing parties – on the threat posed by the West.

amuBhungane reported in May this year that the six parties – the ANC, Zimbabwe’s Zanu-PF, Mozambique’s Frelimo, Angola’s MPLA, Namibia’s Swapo and Tanzania’s CCM – had claimed that Western powers were using opposition parties, NGOs and hashtag campaigns such as #ZumaMustFall as “Trojan Horses” to bring down governments in those six countries.

The report “singled out the USA as the lead country in the international regime change agenda” and also seeks to implicate the UK and Germany.

“Regime change as an agenda”, the Diagnostic Organisational Report continues, “is a reality facing all progressive governments in developing countries. The Russians and the Chinese characterise regime change as ‘the increasingly widespread Western practice of overthrowing legitimate political authorities by provoking internal instability and conflict against governments that are considered inconvenient and insubordinate to their interests, replacing them with pliant puppet regimes that then pander to their interests’.”

The colour revolution had already erupted in South Africa, Mantashe suggested, as elements of it “are visible in the protests we have seen in recent times. For example, Marikana, #FeesMustFall, and #ZumaMustFall movement.

“The programme [of Colour Revolution] seeks to guarantee the West access to the natural resources the developing countries are endowed with, and also have those countries as their markets.

“This is not a new phenomenon in southern Africa where it appeared in 1983. Robert Cooper, who was a Foreign Affairs adviser to Tony Blair, outlined the rules as: ‘The challenge to the postmodern world is to get used to the idea of double standards. Among ourselves (West), we operate on the basis of laws and open co-operative security. But when dealing with more old-fashioned kinds of states outside the postmodern continent of Europe, we need to revert to the rougher methods of an earlier era-force, pre-emptive attack, deception and whatever is necessary to deal with those who still live in the nineteenth Century world of every state for itself. Among ourselves we keep the law, but when we are operating in the jungle, we must use the law of the jungle’.”

On its face, this is a pretty Machiavellian view of the world and one which Mantashe might rightly seem to be warning southern African about. But, as usual, context is critical and this quote has clearly been taken out of context. It is an extract from an essay Cooper wrote in 2002- not 1983- called The New Liberal Imperialism. That too, is not a title that would naturally endear itself to the ANC, containing, as it does, two (or possibly three) of the dirtiest words in its vocabulary.

But it was by no means a word of advice to British Prime Minister Tony Blair to invade southern African states in order to seize their mineral wealth, as Mantashe would have us believe.

Cooper wrote it in the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks in the US, to try to help his government comprehend the new threats posed to itself and to Europe which those attacks had revealed.

Cooper said that Europe had become a “post-modern” order whose states had surrendered much of their sovereignty for the common good and no longer conducted warfare against each other. But he warned that it had therefore become complacent about its security and had become vulnerable to attack by “modern” states – i.e. “those who still live in the nineteenth Century world of every state for itself”.

As examples of these “traditional” modern states “who behave as states always have, following Machiavellian principles and raison d’ètat”, he gave India, Pakistan and China.

Cooper said that if there were to be stability in this “traditional modern” world “it will come from a balance among the aggressive forces. It is notable how few are the areas of the world where such a balance exists. And how sharp the risk is that in some areas there may soon be a nuclear element in the equation.”

In fact there already is very much a nuclear element in the equation, as China, India and Pakistan are now nuclear powers and North Korea has, since Cooper wrote his paper, moved to the brink of becoming one. If it does, others may follow.

His paper makes very clear that he was warning that the peaceful, complacent, post-modern Europe had become vulnerable to attack by such Machiavellian “modern” states, especially when armed with nuclear weapons.

In other words, when he proposed the use of “rougher methods of an earlier era-force, pre-emptive attack, deception”, it was essentially a defensive posture to counter perceived aggression against the West. And this posture was to deal with the “traditional modern” states, not any in Africa. The “jungle” he was referring to, whose law post-modern Europe should revert to when dealing with them, was the likes of India, Pakistan and China.

Whether or not Cooper was thereby revealing his own post-9/11 paranoia in proferring this blunt advice is another issue. But he certainly wasn’t proposing that the UK or Europe at large should invade Africa to impose a new liberal imperial order and seize its minerals.

Cooper appeared to put much of Africa, though surely not South Africa into a different category of “pre-modern” states – often former colonies – “where the state has failed and a Hobbesian war of all against all is under way (countries such as Somalia and, until recently, Afghanistan)”.

Where such states posed a direct existential threat to the West – such as the Taliban-controlled Afghanistan had done by harbouring al-Qaeda – the West would need to intervene to remove that threat.

Otherwise he proposed what he called “voluntary imperialism” to deal with such pre-modern states, by which he essentially meant more of what already existed, such as lots of aid, especially aid directed at improving governance, to help such states graduate out of their Hobbesian condition into the globalised world.

This is the “liberal imperialism” of his title, which was no doubt insensitive to the feelings of former colonial subjects, but was, in fact, rather innocuous in its proposals.

Did Mantashe read the full Cooper essay? Perhaps he did but found that quote about applying the law of the jungle too fit for the ANC’s ideological purpose to ignore.

Or perhaps Mantashe was deliberately cloaking himself in ultra-orthodox, more-anti-imperialist-than-thou, ANC foreign policy ideological rhetoric in order to protect his left flank against attack by the Jacob Zuma/Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma camp while he rebuked it for using the regime change narrative as a diversion from state capture.

“Regime change,” “white monopoly capital” and like slogans are of course being quite successfully brandished by that camp to whip up flagging support in the wake of all the Gupta state capture revelations and many other instances of corruption.

In his report Mantashe lectured Zuma and Co in schoolmasterly fashion about their abuse of the regime change narrative, saying that “linking regime change to state capture reflects the decline in our analytical capacity”.

His report explicitly raised not only state capture, but specifically its arch- exponents, Zuma’s Gupta friends, as an issue that was bleeding ANC support.

Mantashe’s report also noted that the internal divisions and weaknesses in the ANC caused by the state capture controversy “reduce the capacity of our movement to withstand, fight and defeat the offensive. The intensity of our internal fights makes it impossible for the movement to appreciate the threat to the revolution.”

His report was adopted by the policy conference despite attempts by the Zuma camp to suppress it. So it seems the rather enigmatic Mantashe succeeded in his strategy of reclaiming the regime change narrative.

Though at some cost to the reputation of his own “analytical capacity”.

The late African writer Ali Mazrui once warned the ANC of the “four Vs”, according to foreign policy analyst Oscar van Heerden. He said the organisation had moved from being a victim in the apartheid era, to a victor in 1994. By 2004 it had moved into the vanguard of the struggle for equality for developing states.

But Mazrui had also warned the ANC, “Let’s hope you don’t end up being villains” – as Mugabe’s Zanu-PF had become, Van Heerden said.

The real problem with the ANC, though, is that it has never really got beyond the first V. It has never stopped feeling like a victim. Cooper’s essay shows that others also sometimes feel victimised. Which can also sometimes lead to villainy. DM

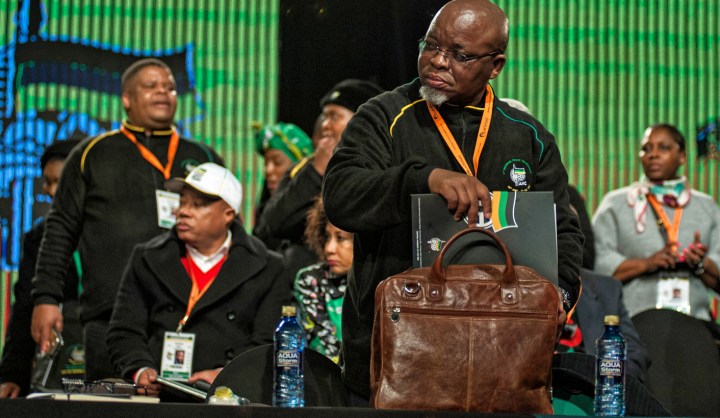

Photo: Gwede Mantashe at the ANC Policy Conference. (Ihsaan Haffejjee)