Politics, South Africa

Oliver Tambo Centenary Series, Part 3: Does the Constitution stand in the way of radical land reform?

In a four-part lecture delivered as part of the Oliver Tambo Centenary Series different aspects of the Constitution will be tackled and tied in to critical issues facing the country right now. In part two we look at the issue of property rights and redistribution of land. Hot debates are raging on how this should be accomplished and on the necessity, if any, for compensation. One proposal is that the Constitution needs to be amended to remove the requirement of paying just and equitable compensation for land expropriated for redistribution. The debate has extraordinary resonance for almost all South Africans. As one of the ANC negotiators at Kempton Park who worked directly on the question of property and land redistribution, I would like to contribute certain reflections of my own to the debate. By JUSTICE ALBIE SACHS.

I would like to share the strategies on land redistribution that we developed at workshops organised by the ANC Constitutional Committee working with ANC militants, engaged academics from the University of the Western Cape and elsewhere, and land activists from different parts of the country. In doing so I will deal with how we countered conservative attempts to entrench the right to free enterprise and the principle of willing seller, willing buyer into the Constitution; and why we chose 1913 as a pivotal date for a twin-track strategy to achieve comprehensive land reform. I will conclude by explaining why I believe that the realisation of the full potential of the Constitution as presently worded would make radical and sustainable land redistribution eminently achievable.

Workshops on the equitable access to land question

Shortly after the first legal conference of the ANC in 30 years on South African soil was held at the University of Durban Westville (UDW) Sports Hall in Durban in 1991, the organisation’s Negotiations Commission was set up with Cyril Ramaphosa and Frene Ginwala at its head. This Commission answered directly to the National Executive Committee, which had the last word on all its work. In developing its ideas and texts it relied heavily on inputs from the Constitutional Committee, most of whose members had by then returned home from exile. A number had taken up positions at the Community Law Centre [CLC] at UWC [Zola Skweyiya, Bridgette Mabandla, Kader Asmal and myself]. Meanwhile the ranks of the committee had been augmented by people like Pius Langa, Dullah Omar, Bulelani Ngcuka, Fink Haysom and Essa Moosa, while Nelson Mandela had specifically asked if Arthur Chaskalson and George Bizos could attend as active participants. We worked in a frenzy, day and night, travelling all the time throughout the country, overseas. I remember joking at the time that the second most important figure in the ANC after Mandela was Rivonia Trialist Andrew Mlangeni – he was responsible for issuing all plane tickets.

We were quite a team, and some issues we could deal with purely on the basis of discussion amongst ourselves. But there were many other questions where we felt we needed to be guided by the findings of broadly based workshops. As a result, the CLC and the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) at UWC began to work closely with the ANC Constitutional Committee to organise a series of workshops on key constitutional issues. All the ANC regions sent participants and many progressive social change campaigners from different parts of the world joined us. The topic on which we had the greatest number of workshops was that of property and land redistribution, the theme of this presentation.

Our debates were spirited and open, enriched by the participation of people throughout the country who had been actively involved in resisting forced removals. They included leaders of rural communities who had fought against eviction themselves, like “Mam Lyds” (Lydia Ngwenya/Kompe) of the Transvaal Rural Action Campaign, who I am happy to learn is still active on land issues in Limpopo. Also with us were activists and lawyers who had dedicated themselves to supporting struggles against forced removals.

We ultimately emerged from the UWC-organised workshops with three strategic propositions on land.

Proposition One: The Constitution as a whole should be a transformatory document

The first shared understanding was that, looked at as a whole, the Constitution should be a document that in a principled and comprehensive way recognised the need to correct the systemic and continuing injustices of the past. This meant that it should not entrench any specific economic model nor be used as a mechanism for freezing the status quo. Rather, the Constitution should leave it to the democratically elected Parliament to find the best way to achieve substantive equality for the formerly oppressed people in their daily lives. We were aware that in many countries property law was founded on the principle that “possession is nine-tenths of the law”. In South Africa, however, it had to be based on an acknowledgement that dispossession had become nine-tenths of the law. This meant that, far from allowing property rights to protect the grossly unjust patterns of land ownership in terms of which 15 percent of the population owned 87 percent of the land, the Constitution had to require and facilitate redistribution.

Proposition Two: Victims of forced removals after 1913 should get their land back or alternative restitution

The second proposition was that victims of forced removals in the 20th Century should be provided with mechanisms to get their land back or alternative redress. I recall that we had very extensive discussions about how far back we should go in relation to restitution for forced removals. Eventually we decided that the Natives Land Act of 1913 could serve as a significant strategic marker. That was the date when the full territorial weight of white supremacy throughout the Union of South Africa had been established. It had been the signal moment when the historic dispossession of the African people had been formally consolidated on a nation-wide basis in terms of express racist legal title.

After 1913, and particularly after the Nationalist Party came to power in 1948, three-and-a-half-million people had been forcibly removed from their homes and land. The unofficial slogan had been: “K….. op jou plek, K….. uit die land” (K….. in your place, C….. out of the country). The obliteration of District Six in Cape Town and Sophiatown in Johannesburg had become just two of hundreds of notorious episodes of relentlessly imposed racist rule. There had not been a city or dorp in the country where the pain of forced removals had not been felt. In the urban areas this had been brought about mainly through the Group Areas Act. In rural areas it had largely been effected under section 5 of the Native Administration Act of 1927, in terms of which the racist government forcibly “got rid of” what they called “black spots in white areas”.

Protracted campaigns to resist these removals had been particularly fierce in the 1980s. At the time when the workshops were convened it was well known precisely who the dispossessed people or communities were and what the areas of land had been from which they had been expelled. The workshops decided that the Constitution should provide that these victims of forced removals should benefit from a clear and direct right to restitution, either in terms of getting their land back or receiving some other equivalent form of redress.

Proposition Three: Extensive programmes of land reform to deal with colonial dispossession before 1913

After much discussion we decided that a different strategy for re-distribution would be required in relation to the historic dispossession that had taken place in the 19th century and before. The third workshop proposition was that there should be constitutionally directed mechanisms to facilitate extensive programmes of land reform to deal with this dispossession. The extent and consequences of the dispossession over the centuries was not in dispute, nor was the need for remedial action. Our preoccupation was with how to develop a strategy that would redress the history of land usurpation in South Africa in a just, rigorous, law-based, implementable and sustainable way. Whereas direct restitution or redress would be relatively easy to accomplish in the case of dispossession that had taken place in the 20th century, a much more complicated process would be required in relation to land that had been usurped by processes of conquest and annexation in earlier centuries. It would have to be driven more by broad political and constitutional considerations and less by formal legal factors.

We were influenced to some degree by problems of an evidential nature. Where would we get dependable proof of precisely who had been dispossessed from precisely what pieces of land? The generations who had suffered the dispossession were no longer alive to testify, and oral tradition passed down through the generations could be slanted in favour of certain families. Furthermore, comprehensive title deeds identifying specific portions of land would not be available. Our main concerns were not about evidential proof, however, but substantive in nature. We came to realise that to attempt to base land reform on who precisely had been dispossessed from what piece of land at what precise moment would be both difficult to accomplish and dangerous in consequence.

We asked ourselves: if a pre-colonial audit was attempted, how far back would it go? Would it start with the Khoisan hunter-gatherer communities who had been the first known inhabitants of much of Southern Africa? Or would it go back to the first pastoral African communities who slowly over the centuries migrated from their kingdoms in the north; or would it begin with the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck in 1652 and the slow gun-bearing penetration into the southern interior by Dutch- descended farming families? Would the audit seek to track the complex, ever-changing patterns of land occupation, use and ownership in the Eastern Cape where British colonial rule slowly advanced northwards during the 100 years of African resistance to conquest in what the British called “Frontier Wars”? Would it be before or after the British used divide-and-rule land grants to pit what they called the “loyal” amaMfengu against the “rebellious” amaXhosa?

We were aware of the rise of the Zulu kingdom as one of the great moments in South African history, with enormous implications for patterns of allegiance and control over land in what is now KwaZulu-Natal. Internal struggles took place. Battles were also fought by African communities with the Boers and the British. Where and when in relation to each piece of land would the moment or the moments be that demarcated the end of the pre-colonial era and the beginning of the colonial? Would the audit predate the widespread disruption resulting from the Mfecane that completely changed the political map of the centre of Southern Africa and led to large-scale movement and reorganisation of African communities? I remember someone raising the question of whether the boundaries of Lesotho would have to be extended to include the large portions of the Free State that had originally belonged to the Basotho nation established by King Moshoeshoe. What claims to what pieces of land would groups like freed slaves, occupants of mission lands and Griqua communities have? Treaties regarding land occupation had been regularly established between Bantu, Boer and Brit, and as regularly reneged upon as the British Empire extended its realm.

Basically, all these queries stemmed from the issue of whether the audit could or should even attempt to privilege any particular moment or moments in the centuries during which the indigenous peoples of southern Africa ceaselessly moved from one spot to another. African communities had adapted to new circumstances and constantly changed both internal and external allegiances, with endlessly evolving patterns of alliance, subordination and domination.

The problem did not stop at determining who exactly should be classified in the historical record as having been the rightful pre-colonial owners of what could be every piece of land in South Africa. An equally severe problem would be to decide who today would be the rightful descendant/beneficiaries to whom restitution should be made. Would the many millions of Africans who had migrated in the colonial period from ancestral land to other parts of South Africa, be automatically excluded from the benefits of land reform?

The basic fact we were confronted with at the workshops was that African societies, like all societies, had not remained static; they had recomposed themselves in a multiplicity of ways. Marriage across ethnic or clan groupings was common. While respect for particular languages and aspects of culture had remained constant, allegiances and identities had constantly morphed beyond fixed ethnic formations. It was Dr Verwoerd who had sought to impose timeless tribalised personalities on African peoples, attempting to root their sealed-off identities in so-called ancestral homelands. The objective was to deny them the right both to achieve unity as Africans across the southern part of the continent as well as to enjoy full and equal citizenship with their compatriots of European, Asian and mixed origin in a united South Africa in which they would be the majority.

At the workshops, then, we were concerned about not allowing the land restitution process to become a vehicle that would end up reversing our age-old struggle to create a united country. We were particularly uneasy about the possibility of land claims leading to a process of “Bantustanising” the whole country. Would the traditional leaders – many of whom had actively supported, and almost all of whom had benefitted from, their links with Pretoria – would they claim to be the only true descendants of the original owners of the land? Would the actual farm-worker families be left out? Would the millions of Africans who had spent their lives in the cities fighting to bring down white supremacy be excluded from any claim to access to the land? It all boiled down to a deep anxiety that if access to land was directly related to precolonial political systems, then the very ethnic divisions that the ANC had been established to overcome, would be revived. The Tambo dream of a united South Africa would implode at the exact moment of its realisation.

We concluded that the broad strategy for dealing with historic dispossession should not be based on returning particular pieces of land to particular ethnically defined descendants. Rather, the strategy should be founded on an understanding that black people as a whole and in all parts of the country had suffered from dispossession. Similarly, black people from all over the country had fought for freedom and a new constitutional order. It followed that in principle black people throughout South Africa should be potential beneficiaries of legislatively driven land reform. Precisely how this should be accomplished was something to be left to the new democratically elected Parliament.

In our workshop discussions we canvassed many options for de-racialising the patterns of ownership. The mix of potential interventions ranged from imposing taxes on unused land, to creating large public-private or state or cooperative farms, to outright expropriation, to facilitating mixed forms of ownership. I personally favoured the development of new legal forms to catalyse the creation of varied models of joint interest between farm workers and farm owners. This would give the tillers of the land a secure legal interest that went beyond simply wages and a place in which to live. Their equity stake could expand over time to give the workers an increasing share of the equity. Technically this should be feasible. After all, with a view to maximising commercial profitability, one of the most ancient principles of South African property law, namely that the owner of land automatically owned all buildings constructed on the land, had been changed by statute to allow sectional title for multiple owners of portions of a building. I saw no reason then and see no reason today why, in the interests of facilitating the constitutional imperative of land reform the law could not be adapted to accommodate multiple concurrent and mobile interests in rural land.

We envisaged that in conditions of democracy the people working on the farms would become well-organised and have a large say in relation to their conditions of work and life as well as to their possible legal interests in the farms. One of our strongest debates was in fact whether preference of land reform should be given to the landless poor, or to African people with some capital who would be better situated to derive immediate economic benefit from the land. But these were all issues that we felt should be left to the newly elected Parliament and Government, and not be pre-determined by the drafters of the Constitution.

It needs to be stressed that the provisions that appear in our Constitution relating to property and land redistribution were not negotiated at Kempton Park. They were the product of prolonged and intense deliberations at the democratically elected Constitutional Assembly. Since I was sitting on the Constitutional Court at the time, I had no role at all in the drafting process of the final Constitution. But I understand from those who did take part that while the text was being debated dynamic public hearings were organised by Snakes Nyoka in various parts of the country; I was told too that the terms of Section 25 were hotly contested throughout in the Constitutional Assembly and directly influenced by the views of thousands of people literally on the ground. What seems to be clear from the wording of the text itself is that in the Constitutional Assembly, where the ANC had more than 65% of the seats, the deliberations were also heavily influenced by the above-mentioned three propositions on property and land re-distribution that had emerged from the workshops organised by UWC and the ANC Constitutional Committee.

The text of Section 25 appears at the end of this paper. In the full version of the paper [www.tambofoundation.org.za] I discuss in some detail the various textual provisions of the Constitution that have a direct or indirect bearing on the question of land redistribution. I mention in summary here that Section 25 does not impose a willing seller, willing buyer test for compensation for land expropriated for redistribution; on the other hand, it does expressly require that land reform be facilitated; that the processes be law-governed; that expropriation be permitted in the public interest and that the criteria for ensuring that compensation is just and equitable be such as to permit payment of amounts well below market value; that the state be obliged to make restoration to victims of forced removals after 1913; and that the state be given considerable latitude in how to effect redress in relation to the effects of conquest and dispossession in the centuries preceding that date.

Looking forward

Far from being a barrier to radical land redistribution, the Constitution in fact requires and facilitates extensive and progressive programmes of land reform. It provides for constitutional and judicial control to ensure equitable access and prevent abuse. It contains no willing seller willing buyer principle, the application of which could make expropriation unaffordable.

The judiciary could play an important role in determining whether the just and equitable principle could be applied in a manner which would substantially reduce the costs of expropriation. I support the suggestion by my colleague, former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke, to have the matter of compensation tested in court. It is perhaps unfortunate that so few cases have as yet been brought to test the application in practice of the ‘just and equitable’ formula. One that has been hailed as a groundbreaker is the Land Claims Court ruling in July 2016 by Advocate Tembeka Ncgukaitobi in which compensation was set below market value. This decision has been celebrated for championing the progressiveness of the Constitution on land reform.

Yet while the courts could play an immediate role in establishing the broad lines on which Section 25 should be interpreted, court orders would not appear to be the best instruments for defining and structuring the institutional arrangements for making determinations and establishing modalities of payment. It is urgent that the existing expropriation legislation, which dates from the pre-Constitutional era, be replaced by a new law centred on the provisions of Section 25. This would not only reduce the costs of acquiring land for land reform. It would also lower the cost of securing land for providing housing and enforcing other social and economic rights. A new Expropriation Bill that updates the compensation requirements in line with the Constitution was recently taken through Parliament by Jeremy Cronin. Opposition was mobilised by the Institute of Race Relations and instead of signing it into law, President Jacob Zuma sent it back to Parliament on the grounds that consultation had been insufficient. The finalisation of this new legislation is clearly urgent.

Parliament could also attend to its constitutional obligation in terms of sec 25 [9] by adopting legislation to strengthen the legally insecure forms of tenure given under apartheid to black people and communities. Considerable work was done in the early years of our democracy to protect housing, burial and other rights of farmworker families on land they had long occupied. But little has been achieved for the millions of people living on what is referred to as ‘communal land’ in the former Bantustans. Their rights to use and develop the land in a meaningful way remain extremely insecure. This insecurity perpetuates the divisions created under apartheid in which the Bantustans were seen as rural backwaters intended to supply cheap migrant labour for the farms, mines, industry and homes of the whites in the developed parts of the country. Section 25 [10] requires Parliament to take steps to upgrade the tenure rights of those who bore and continue to bear the heaviest pains of apartheid dispossession. Significant rural prosperity can never be achieved unless the rights of people living and working in the former Bantustans to own and develop the land on which they live, are adequately secured.

Finally, Parliament could also use its compendious reserve power under sec 25 [8] to fill in gaps and drive the redistribution process forward. One project that has enormous potential would be to develop forms of joint legal interest between current farmworkers and farm owners. The tillers of the land, many of whose families had been there for generations, could be given a secure legal interest in the land that went beyond protection of wages and housing rights. Financial mechanisms could be created to enable their equity stake to expand over time to become full ownership. Current owners would have incentives to help ensure that food production would be maintained. Sweat equity and legal title could be reconciled. The words of the Freedom Charter could become true: The Land Shall Be Shared Among Those Who Work it.

Furthermore, there is nothing in the Constitution that restricts land reform to rural areas only. Vigorous, creative and sustainable public law interventions could play a major role in overcoming the spatial apartheid divisions that continue to bedevil our cities. Not only do they perpetuate social injustice; they are wasteful and inefficient and prevent the full potential human, cultural and economic richness of our urban fabric from being achieved.

Our current Parliament has in fact set up a high level advisory panel headed by former President Kgalema Motlanthe to review all the legislative steps that have been taken since 1994 to deal with social and economic conditions, including those relating to land redistribution. I understand that at a number of hearings on land conducted by the Panel, people have asked for the return of land to them as the community, ethnic or clan descendants of those who had once resided and worked as owners of the contested pieces of land. Any review of land redistribution policies today would have to pay special attention to the question of how precisely to fit in the specific claims of specific communities to specific pieces of land, with the claims of black people as a whole to have equitable access to land throughout the country.

I would not wish to anticipate any findings this Panel might make. But it appears to me that any deficiencies with land reform thus far have stemmed from failure either to use at all or to exercise effectively the full powers given under the Constitution. The Constitution as it stands provides powerful instruments to bring about comprehensive land reform. The problem so far has been one of implementation rather than of impediments created by the Constitution. Before seeking to amend the Constitution, it would be wise to utilise its redistributory powers properly and to rely on the fact that the Constitution is a living tree capable of responding creatively and with vigour to new problems.

The issue of land redistribution has huge resonance for the great majority of South Africans. It is precisely for this reason that it needs to be handled in a well thought through and participatory manner. Thus, even abolishing completely the need for compensation would not resolve the question of who the beneficiaries should be in relation to any particular pieces of land. Nor would it solve the questions of how to organise farming so as to sustain and advance agricultural production. Amending technical aspects of the Constitution is one thing. Amending the Bill of Rights would be another. It would be particularly problematic if the proposed amendment in its specific South African context became entangled with the Preamble and the foundational principles of non-racialism and the rule of law.

Some are asking whether it is logical to denounce colonialism for seizing the people’s land without compensation and then use the very morality we have condemned to obtain redress. They point out that Oliver Tambo’s enormous moral and political strength came from the integrity of a vision that taught us not to use torture against captured enemy agents just because torture was being employed by them against us; that we should not respond to massacres of our people by using terrorism against civilians ourselves. Yet at the same time it would be grossly illogical to exclude the nefarious history of land dispossession from any reckoning on how to spread the costs involved in effecting land re-distribution.

There can be no denying that a new dedicated approach to land reform is required. This can be achieved in a well-informed, principled and participatory way. A good start would be to do an honest and self-reflective audit of all the measures taken since 1994 to promote land reform. The aforementioned Panel set up by Parliament and headed by Kgalema Motlanthe holds immense promise in this respect. We need to be able to learn from past successes and past failures.

Our Constitution was created through principled national dialogue, as envisaged by Oliver Tambo. If dealt with in the same way, the Equitable Access to Land Question, perhaps the most compelling and unresolved problem of our time, has the greatest prospect of success. DM

Annexure:

The Property Clause in the final Constitution

Section 25 of the Bill of Rights

25. (1) No one may be deprived of property except in terms of law of general application, and no law may permit arbitrary deprivation of property.

(2) Property may be expropriated only in terms of law of general application?

(a) for a public purpose or in the public interest; and

(b) subject to compensation, the amount of which and the time and manner of payment of which have either been agreed to by those affected or decided or approved by a court.

(3) The amount of the compensation and the time and manner of payment must be just and equitable, reflecting an equitable balance between the public interest and the interest of those affected, having regard to all relevant circumstances, including?

(a) the current use of the property;

(b) the history of the acquisition and use of the property;

(c) the market value of the property

(d) the extent of direct state investment and subsidy in the acquisition and beneficial capital improvement of the property; and

(e) the purpose of the expropriation.

(4) For the purposes of this section ?

(a) the public interest includes the nation’s commitment to land reform, and to reforms to bring about equitable access to all South Africa’s natural resources; and

(b) property is not limited to land.

(5) The state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to foster conditions which enable citizens to gain access to land on an equitable basis.

(6) A person or community whose tenure of land is legally insecure as result of past racially discriminatory laws or practices is entitled, to the extent provided by an Act of Parliament, either to tenure which is legally secure or to comparable redress.

(7) A person or community dispossessed of property after 19 June 1913 as a result of past racially discriminatory laws or practices is entitled, to the extent provided by an Act of Parliament, either to restitution of that property or to equitable redress.

(8) No provision in this section may impede the state from taking legislative and other measures to achieve land, water and related reform, in order to redress the results of past racial discrimination, provided that any departure from the provisions of this section is in accordance with the provisions of section 36(1).

(9) Parliament must enact the legislation referred to in this subsection (6).

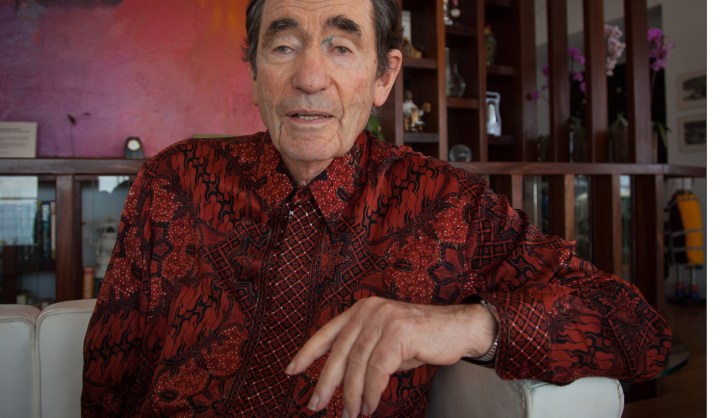

Photo: Albie Sachs, by Steve Gordon.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider