South Africa

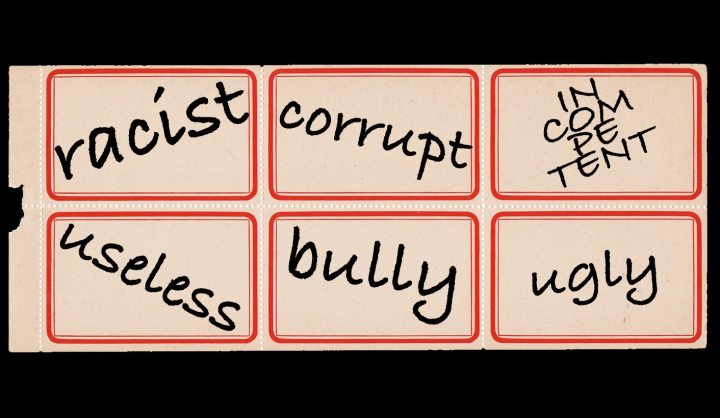

Op-Ed: The rise of Label Weaponry and the shattering of public discourse

Anarchists, hooligans, opportunists, third force. Elements pushing a regime change agenda. These labels have increasingly featured in the public discourse courtesy of the governing ANC. Who is at the receiving end of such characterisation? Anyone challenging the dominant power structure – from NGOs and trade unions to opposition parties to students. Heavy on insinuation but light on specifics, it’s a tried-and-tested ANC tactic to shut down contestation, but the result is a Pontius Pilate-like washing of hands by the governing party over its failure to resolve the internal conflicts that infect the broader body politic. By MARIANNE MERTEN.

The run-up to the 2002 ANC Stellenbosch national conference successfully used labels – then it was “ultra-leftist” – to isolate those aggrieved by the then economic regime of the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (Gear) programme. At the time, trade unions, labour federation Cosatu and the South African Communist Party (SACP) vocally opposed the road taken by then president Thabo Mbeki. Slammed as anti-worker and a neoliberal favouring those already favoured in the economy, opposition to Gear meant relationships in the tripartite alliance sank to an all time low.

That ANC conference deemed ultra-leftism counter-revolutionary, just like neoliberalism, amid criticism of “careerists” and those “too many moneyed people used to buying their way” into the ANC, as it was put by then secretary-general Kgalema Motlanthe. Instead there was the call for the “RDP of the soul” and, according to the Mail & Guardian, a new cadre to guard against corruption of fellow comrades, to selflessly serve communities, to identify needs timeously and to “defeat the concept that service in local government means catching the last coach of the gravy train”.

Fast-forward a decade to the 2012 Mangaung ANC conference. Amid condemnation of slates, or the practice to elect predetermined sets of leaders, the call for a “new cadre” again emerged. These “new cadres” were to be forged, according to the conference resolutions, over the next decade through political education, academic training and skills development.

“This includes a deliberate and extensive leadership programme at all levels of the democratic movement as part of giving effect to the call made in the 2000 NGC (national general council) for a ‘new cadre’,” said the Mangaung resolutions. “As we mark the centenary, we are determined to enhance the ANC moral standing and image among the masses of our people, and address the sins of incumbency. In this regard, we shall combine political education with effective organisational measures and mechanism to promote integrity, political discipline and ethical conduct and defeat the demon of factionalism in the ranks of the ANC, alliance and broad mass democratic movement.”

The resolution came four months after police killed 34 miners at Marikana. For months, tensions brewed between Cosatu’s National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and the Associated Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu), which had clinched a more favourable deal for rock drillers at Impala Platinum in early 2012. At the time the NUM, then headed by general secretary Frans Baleni and president Senzeni Zokwana (today the agriculture minister), had declined to negotiate for those doing the most back-breaking work on the lowest salaries.

The response from the comfortably entrenched labour elites – NUM at the time was Cosatu’s largest union – was to label Amcu as upstarts, to try to delegitimise its leadership as disgruntled expelled former NUM members. Yet that had happened 14 years earlier and Amcu, formally registered as a trade union in 2001, was firmly entrenched in the coalfields around eMalahleni, reaching out elsewhere in the mining sector. It had done the work: organise, recruit and represent workers and their interests.

Instead Amcu leader Joseph Mathunjwa was described as a “spy” who was in touch with Western agents, in at least one (discredited) intelligence dossier, which took a similar line on then Cosatu general secretary Zwelinzima Vavi amid the ructions in Cosatu from 2013. Similarly, Numsa and its leadership were labelled “opportunists” and “factory faults” on the tense road that ultimately led to the metal workers’ union’s expulsion in November 2014.

Coincidentally, the spy label was also stuck on Public Protector Thuli Madonsela during the Nkandla probe by Deputy Defence Minister Kebby Maphatsoe. Also thus labelled were former DA parliamentary leader Lindiwe Mazibuko, Economic Freedom Fighters leader Julius Malema and others, in a discredited blog. Nevertheless the State Security Agency (SSA) decided to investigate this.

The politician in charge, State Security Minister David Mahlobo, has since insinuated that there were ulterior motives in last year’s #FeesMustFall student protests, said to have received foreign funding. And in his budget speech briefing in April, Mahlobo claimed NGOs were not what they seemed: “There are those who are used as NGOs, but they are not. They are just security agents that are being used for covert operations.”

This week Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande, the SACP top commissar, according to Business Day, told the Young Communist League that “students should not be demanding free education from the state, they should be demanding it from the capitalist classes”.

Yet the Freedom Charter, which the ANC and its alliance partners hail as South Africa’s founding document underlying the Constitution, states, “Education shall be free, compulsory, universal and equal for all children; higher education and technical training shall be opened to all by means of state allowances and scholarships awarded on the basis of merit.”

In the current state of the public discourse, perhaps it’s easier to blame nameless, faceless capitalist classes than own up to government policy misfires.

Similarly, Nzimande, who led the criticism of Numsa, put the troubles in the tripartite alliance on “… forces from outside this country, possibly working with forces inside this country who have no interest in seeing a successful and revolutionary alliance”.

Failure of the alliance partners to meet regularly, to stick to a determined alliance programme outside election times, and repeated inaction by the ANC on its partners’ concerns, including the SAPC’s misgivings about the politically connected Gupta family, suddenly don’t seem to matter. Again, it’s easier to blame unnamed, faceless forces, than look at in-house quandaries.

It is in this context that Cosatu president S’dumo Dlamini can tell The Justice Factor that the labour federation was not involved in the SABC staff suspensions because no one had approached it or any of its affiliates. In any case, said Dlamini, there should not be a blurring of the lines between labour issues and the political.

Yet the National Education Health and Allied Workers’ Union (Nehawu) has been looking for a political solution for the fractured labour relations at Parliament following the unprotected strike over performance bonuses and conditions of work late last year. Seven months down the line, and despite a series of meetings with presiding officers, the political solution remains elusive.

Instead, Parliament has accused Nehawu of “a political agenda to destabilise Parliament”. Or, as the national legislature put it in May: “This is a clear political agenda masquerading as a shop floor matter waged against Parliament and the Secretary to Parliament by individuals who have declare that they want to render important parliamentary business ‘unworkable’ and the institution ‘ungovernable’.”

And so the labels of opportunists, anarchists and hooligans – also readily and regularly dished out by the ANC parliamentary caucus to EFF MPs amid the past two years’ terse politicking in Parliament – remain strongly in play on all fields.

The claims of underhand shenanigans from the governing ANC are coming faster and more furiously. Perhaps it’s the election campaign trail that has flipped on hyperdrive.

In Tshwane, as in Vuwani, the ANC and the government it leads insisted that opportunists, criminal elements and shadowy forces fanned the protests. What has emerged, however, indicates a very different picture – one in which a significant role is played by those local and regional ANC interests feeling threatened by a new set of dynamics.

In Tshwane, it was the parachuting in of Thoko Didiza, one of Parliament’s three house chairpersons, as ANC mayor candidate, rather than the continuation of the prevailing arrangements that benefited the elites. In Vuwani, it was redemarcation that lit the proverbial fire to ensure that elite interests would continue. And so schools burnt, buses went up in flames, and foreign-owned spaza shops once again were looted and set alight.

It’s not always the case that factional interests burst into violence. The system of governance, with the selective blurring of the lines between party and state amid the ANC’s deployment policy, allows for the ticking of boxes without heed to substance so it all looks good on paper.

The controversy over the SABC, which has now ruptured publicly amid protests over censorship, seven staff suspensions and one resignation, has been in the making for a long time. One of the main culprits is Parliament, whose communication committee has been derelict in its oversight and legislated role. Six of the 12 non-executive seats on the public broadcaster’s board are vacant, and have been for up to two years.

The factional sea changes over whether the ANC approves the direction taken by SABC Chief Operating Officers Hlaudi Motsoeneng – perhaps in part sparked by the ANC’s tendency to close ranks when perceived to be challenged, eve if only by DA court challenges – have not made things easier. One casualty was committee chairwoman Joyce Moloi-Moropa, who is also SACP treasurer, who earlier this year resigned as ANC MP after effectively finding herself isolated following a brief bloom of oversight.

It is against this background that Tuesday’s ANC statement on the SABC must be considered. Opposing “any actions that infringe on our people’s rights to hear and see what they want to hear and see”, ANC chief whip Jackson Mthembu, who is also chairman of the national executive committee (NEC) communications subcommittee, said there would be a meeting on Monday with Communications Minister Faith Muthambi, the ANC deployee to Cabinet responsible for the SABC. Until then the ANC’s contribution to the public discourse regarding the public broadcaster has been to insinuate ulterior motives behind the ructions.

Using labels has several consequences. It reinforces a binary world view of good and evil, in which a hero comes to the rescue. This disempowers just about everyone by removing agency of individuals and communities, be they residents of a particular locale or interest groups like students, trade unions or NGOs. And it makes it easy to feather and tar those who speak out before the anointed hero arrives.

Throwing about labels also means sidestepping critical introspection. The aim is to cast off criticism by delegitimising the other as opportunists, hooligans or even a third force, an echo to the nefarious networks of state security agents and their lethal role in the anti-apartheid struggle of the 1980s and 1990s.

The ANC’s resort to labels in the public discourse also further widens the already open door to securocrats – and the view that those not toeing the dominant factional line as they pursue their struggles, be they students, civil society activists, unionists or investigative journalists, can be targets of surveillance.

And so the public national discourse lies shattered. It comes at a heavy price.

For the first time in 22 years concerns are being voiced, including from the Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC), about the re-emergence of political violence, and not just in KwaZulu-Natal. Several ANC councillor candidates have been killed, as have others from other political parties, while election meetings are disrupted and political rivals clash countrywide.

It is high time to deal with the underlying fundamental issues, no matter how messy or testing these might be in a society as unequal and disparate as South Africa’s. DM

Original photo: Dennison Label Sheet, Calsidyrose via Flickr

Become an Insider

Become an Insider