Maverick Life, South Africa

Literature and Identity: Who’s Afraid of K Sello Duiker?

Jacob Zuma loves a good anniversary. Generally they are meant to distract us from the present by taking us back to a heroic past. The subliminal message is that with heroes like these the ANC couldn’t possibly do what it is doing to people in the present. One anniversary Zuma overlooked however is that 19th January 2016 was the 11th anniversary of the suicide of K Sello Duiker. By MARK HEYWOOD.

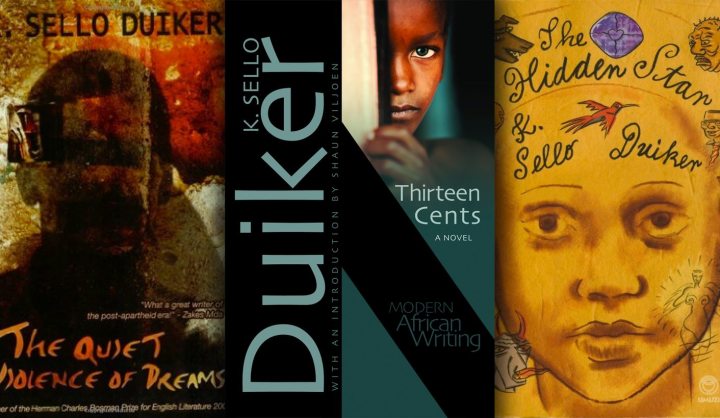

I have recently been reading the short but intense canon – more aptly described as a cannon – of the writings of K Sello Duiker. He wrote three novels before his suicide at the age of 30, an act repeatedly prefigured and contemplated in the novels. I had heard Sello’s name mentioned with reverence from time to time, but it took a chance encounter with him on a bookshelf whilst killing some time at Cape Town International airport to enter his world. And what a world it is.

The Cape Town of Thirteen Cents is not the world the cities designer architects would have us thinking it is. There’s an Azure, the book’s main character, on every corner. Our world unfortunately and fortunately.

All of Duiker’s novels were written before his death in January 2005, but they are a hotbed of the fires that are burning fiercely now around race and identity.

Duiker tumbled out of the cocoon of Rainbow-ism prematurely (he was not alone in this; so did a few other writers) and the fact that he felt so alone in his questions probably contributed to his suicide by hanging. Now the questions he was asking are all the rage in the chatter circles – but little is being done about the inequalities beneath them.

Except Sello goes further and writes about the interfusion of race with class and inequality … which is something most of us have not yet arrived at.

My fear is that beneath the noise of the race debate there are 100,000 new Tshepo’s (the main character in Duiker’s Quiet Violence of Dreams) grappling with the fact that they don’t own a colour in the rainbow. This surely also explains the Nyaope epidemic, now consuming parts of our youth, another issue No 1 didn’t recognise, except in a passing mention about a Mrs Baloyi, a stall-keeper in Marabastad who “complained about Nyaope drug addicts who steal good from traders”.

When the poor turn on the poor its confirmation that there’s sure a lot of despair out there.

That’s my long introduction to a series of questions K Sello Duiker made my mind buzz. The questions are primarily about the importance of black literature in reflecting and shaping all our identities as people in South Africa.

I’d love his publishers and book-sellers to tell me about how his books sell (or don’t) and who they sell to? I’d like those who decide on the set texts to be taught in English literature (should it still be called that) to tell me whether they have ever considered 13 Cents or The Quiet Violence of Dreams as set-texts, and if not why not?

I ask these questions because, during what might be described as a period of national depression, even schizophrenia, Sello’s writing make us think about the role that literature plays in shaping identity/ies. The writer is a weather vane, an early warning system of the cold fronts of our national experience.

Let me give you a for example. I grew up on a diet of English literature and to the extent that there is an English national culture or identity I think that their literature helped shape it. For the English it extends from Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Keats, the Brontes, right through to George Orwell, Ian McEwan and beyond. Many of these ‘classic’ texts are taught in schools, not just examined on, and even if people don’t read the works of these artists beyond their school years these names provide a backdrop to identity, and not of the right-wing UK Independence Party (UKIP) or National Front (NF) kind. Listen to the music-hall punk Ian Dury’s England’s Glory for a parodic celebration of this identity.

At the moment peoples who live in SA are struggling with our identity. Our shared identity used to be the struggle for (or against) freedom. Then for a few years it was the dizzy experience of the rainbow nation, mixed up with rugby, Nelson Mandela and victory in the African Cup of Nations. However in the last few years, as the worthy illusion of rainbow-ism has unstitched and been replaced with Zupta-ism – something few of us can identify with – what we thought/hoped was our identity has fragmented.

Today the forces affecting us are centripetal rather than centrifugal, we are attaching ourselves to surfaces rather than something deeper. The growth of evangelical religions seems to suggest many people have given up on the present and will rally around an identity forged in the invented past and impossible future. Much of this anxiety is linked to growing inequalities and different experiences of Mbeki-ism and Zupta-ism.

Which brings me back to black writing.

25 years ago I converted to African literature under the influence of the writing of AC Jordan and after a brief proximity to the unique persons of Es’kia Mphahlele and Njabulo Ndebele then at the African literature department at Wits University. Between them they opened up a world that stretches back as written literature to the mid-nineteenth century – more than enough to get our teeth into.

We have our Wreck of the Deutschland in SEQ Mqhayi’s Ukutshona kukaMendi (Sinking of the Mendi). We can find our historical dramas in Sol Plaatje, Thomas Mofolo and HIE Dhlomo. We have books at risk of extinction in all but a few minds which ought to be being republished and promoted. Aziz Hassim’s The Lotus People; AC Jordan’s Ingqumbo Yeminyana (Wrath of the Ancestors). We have our modern writers like Sello Duiker, his friend Phaswane Mpe and many names we do not know because the market doesn’t want them.

So here’s the question: why don’t we teach these works systematically in our schools? Why is this canon the preserve of experts and academics instead of readily available on books shelves or taught in schools?

In fact, the NSC 2014 syllabus for literature still appears to be segregated. Those who choose Literature Setworks in English (presumably the majority?) get The Great Gatsby, Animal Farm and Pride and Prejudice (message to trolls: don’t get me wrong these are all great works). Those who chose one of our other 10 official languages get black writers, except the three white writers set for those choosing Afrikaans. All are denied the opportunity of cross fertilization of literatures

The other question is why is it so hard to buy these books?

Exclusive Books might argue that there’s no market, but there is because black writers or books about black leaders are – Bible aside – the books most frequently stolen from their stores. Anyway, I’m sick of the power of the markets (who the fuck are they anyway?) to dictate to every area of our lives, from what we read, what we can watch at the movies (mostly shit) and how much we can spend on fulfilling our constitutionally enshrined rights – surely South Africa’s glory.

We want something better.

The point is that our majority government should be helping us work together to make a market for our literature. Exclusive Books have enough money for grand renovations of their flagship store to excite the predominantly white shoppers of Hyde Park, so why not invest in something a little deeper and more ambitious?

A similar responsibility rests on the Department of Basic Education. Given that textbooks are the most lucrative market for publishers, teaching African literature from grade R and up would create a new market for the books of our past and present writers. It would put money in their purses.

But most importantly it would situate our young minds in their own national and continental context, square them up to our social and political challenges and make the privileged aware of the lives of those they don’t see – even though they are visible all around them. It would start to create an identity in us with our land, its peoples and traditions. Let’s call it black consciousness.

Something worth reclaiming power for? DM

Mark Heywood will be hosting a discussion on this issue this week as the Friday Stand-In on the Redi Tlhabi show on Talk Radio 702 and Cape Talk. Make your views heard.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider