South Africa

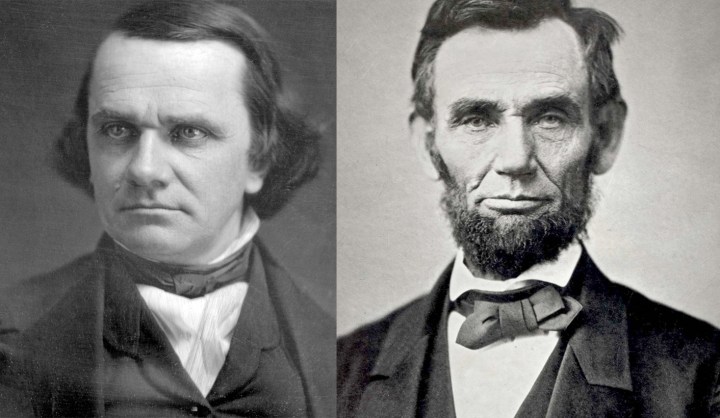

Want a Zuma-Zille face-off? Lincoln-Douglas debates could be the template.

When two very ambitious politicians found a way to debate and frame the issues beginning to rip apart a nation, they willed into being a public tradition that has become a standard element of democratic practice in much of the world. Could their innovation help South Africa in its own search for a way forward (but without the civil war)? J. BROOKS SPECTOR looks back into history to look forward to a future possibility.

In 1858, throughout much of the wild Kansas Territory and eventually even into neighbouring Missouri, pro- and anti-slavery settlers were fighting a small-scale civil war over whether or not Kansas would be admitted to the Union as a state that allowed slavery within its borders. Simultaneously, just a few hundred miles away in nearby Illinois, two men were carrying out a battle for the right to be one of Illinois’ two US Senate seats.

Incumbent Senator Stephen A Douglas, often nicknamed “The Little Giant” by virtue of his political heft and his diminutive height, was the crown prince of his Democratic Party and its almost inevitable nominee for president in the 1860 election, just two years into the future. By contrast, his Republican Party opponent, Abraham Lincoln, aside from some early experience in the Illinois state legislature, had had, years earlier, only one two-year term as a member of the US House of Representatives from Illinois for by then dissolving Whig party. However, he had been making a name for himself as a skillful, successful lawyer and public speaker on the main public issues of the day. He launched his campaign for the Senate with his now-famous “A house divided” speech delivered in the state capital of Springfield on 16 June 1858. In that speech, he had effectively accused his Douglas of holding a “care not” policy about slavery. In effect, Douglas was trying to be all things to all people on the issue as a politician sans moral core to confront the nation’s primary political crisis.

In oratory that marked him for larger things, Lincoln had said in that speech, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved; I do not expect the house to fall; but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the states, old as well as new, North as well as South.” Lincoln delivered this speech at his party’s nominating convention on 16 June 1958 and, in his rhetoric, he had found the scriptural voice that eventually became both trademark and touchstone for his powerful, instantly recognisable style.

The Republicans as a political party were then new boys on the political block. Their party had only recently come together as an amalgamation of northern Democrats increasingly reluctant to defend the continuation of officially protected slavery, more radical Whigs (like Lincoln) who were convinced slavery would eventually tear the country apart if the issue was not resolved, and a new emerging constituency of thoroughly anti-slavery citizens who had first created the Free Soil Party and who then merged that party with the other two groups into the new Republican Party. They had yet to win a presidential election, but they were gaining traction in winning lesser offices in many northern states.

For decades, the Whig Party (Lincoln’s original political home) had attempted to avoid the issue of slavery by advocating its “National System” of infrastructure building to expand western settlement. This would deflect the country’s attention away from the slavery question. But as each of the western territories petitioned for statehood in turn, the question of whether they would enter the Union as states that allowed slavery or forbade it helped guarantee slavery was becoming the preeminent national argument. The resulting intra-party tension ultimately broke the Whig Party apart, and the country’s political landscape increasingly entered a state of flux as old political allegiances disappeared and new ones rose to replace them.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party was also increasingly divided by its own difficult straddle over slavery. By the 1850s, the party’s official line was that the question of the extension of legalised slavery would be left up to the majority of the population of each territory, as it became a new state. In effect, the Democrats were arguing slavery could be immoral in part of the country, but acceptable in another, a position that ultimately satisfied nobody. For many Democrats, this awkward position was a recipe for electoral disaster, while for others it was the only way to keep the country – and their party – together.

In the 19th century, the people of each state did not directly elect their US senators – the original constitutional arrangement was for an indirect election. Each state’s legislature was responsible for selecting its two senators. As a result, the Lincoln-Douglas campaign for this Senate seat was actually about whether either candidate could ensure the election of sufficient members of their respective party into the Illinois state legislature so that a candidate could assure selection as senator from Illinois.

Early on in the campaign, Douglas had begun delivering his stump speech around the state, and then Lincoln decided to appear at one of these gatherings to speak to the assembled crowd – an early example of ambush politics. But rather than continue in this ad hoc, cat-and-mouse campaign, Douglas accepted Lincoln’s challenge to participate in a sustained series of debates in each of the seven congressional districts (out of Illinois’ nine districts) where Douglas had not yet delivered his formal set-piece campaign speech. Douglas must have felt he had very little to fear in speaking with Lincoln at joint events, given Douglas’ national reputation for eloquence and political prominence. Lincoln just as clearly must have felt that as the challenger, he had very little to lose and much to gain from tandem performances. He was right – in the longer term.

In keeping with the more leisurely practices of the 19th century where a campaign speech was a sustained public entertainment, the two opponents agreed on a format where one man would speak for an hour, his opponent had an hour and a half for a response, and then the first speaker had thirty more minutes to rebut the second speaker’s remarks. This would mean a total of three hours of sustained, continuous speaking – all without microphones or any other form of amplification. The two candidates alternated going first in their tour around the state.

The debates – took place for almost two months, between 21 August and 15 October 1858 – and quickly became an electrifying national political phenomenon. As the two men and their entourages entered the next town, their joint appearances attracted crowds of upwards of fifteen thousand people for an afternoon of gruelling, live political theatre. Meanwhile, audiences participated by shouting questions and cheering the participants as if they were prizefighters in a bare knuckles grudge match. And they taunted the two candidates with the kind of astonishingly crude racial language that would never be permitted in public nowadays.

Newspapers from as far away as New York City soon began sending reporters to cover this astonishing campaign. And specially assigned stenographers recorded the entirety of all of these three-hour events for posterity. Newspapers around the nation then printed full transcripts of the debates – as Americans followed their progress with enormous interest.

In the end, the citizens of Illinois elected a sufficient number of Democratic Party state legislators that the legislature elected Douglas as the state’s next US Senator, but it was Lincoln who “won” the debates – in the long run, that is. Lincoln took the transcripts of the debates and published them in popular book form. The national attention he received from the debates brought him firmly to the attention of the Republican Party’s national leadership, and his supporters were able to make him their party’s national presidential candidate in 1860 – and then on to victory as president.

Ironically, he faced the very same Stephen A Douglas in the presidential race as well. Douglas had become the Democrats’ candidate, at least in the northern and western states. The party had split into two wings and another candidate, John C Breckenridge, became their standard bearer in the southern states. The last gasp of the remnant Whigs, now re-labelled as the Constitutional Union Party, selected yet a fourth candidate, John Bell, who campaigned solely on preserving the country by postponing any question of confronting slavery as an issue in any way.

Besides focusing the nation’s attention on an issue it could no longer avoid confronting – the continuation, extension or eventual abolition of slavery – the Lincoln-Douglas debates created a new kind of campaigning for office. The candidates took each other on directly, face to face in front of voters, without the mediating influences of distance – or pretty much anything else. These seven debates eventually became the inspiration for the Kennedy-Nixon debates of 1960 broadcast on national television, and those debates, in turn, have become the touchstone for the many political campaign debates that have followed ever since.

And so, is there a lesson for South Africa from all this? There are several, in fact.

Debates can be an excellent way to focus a nation’s attention intently on the key issues confronting a society. Second, a clever PR: skillful politician can use this kind of clash to present a sharply defined difference between themselves and their opponent. Third, a challenger can use the opportunity of a debate to put an incumbent on notice that incumbency offers no guarantee of safety from the clash of ideas and policies. Meanwhile, an incumbent can draw upon their experience and insider knowledge to demonstrate that a challenger simply doesn’t have the depth or breadth of experience for the job. Fourth, debate can be an excellent way to deal with any awkward structural issues about what is the real mechanism for making an electoral choice – the party list process in South Africa now or the old style of indirect elections of senators in 19th century America. Moreover, debate is not, in fact, foreign to South Africans, as some might believe. Rather, it plays right into the traditions of many high schools and universities – historically both black and white – across South Africa where debate has long been a way of exercising the mind and testing ideas and thinking. Finally, debates, simply put, can be great theatre and an excellent method of political education for audiences and voters generally. Are any South African politicians listening? DM

Read more:

- Lincoln-Douglas Debates – History and Significance of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates at the About American History website

- The Lincoln-Douglas Debates at US History.org

- Lincoln-Douglas Debates – 45 Programs, (the C-Span cable TV network carried out a re-enactment of all seven debates and broadcast the result. These are the recorded re-enactments)

- The Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 at the National Park Service.gov

- The Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 at About History.com

Photo: Stephen A Douglas/Abraham Lincoln (Wikimedia Commons)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider