Maverick Life, Media, World

Broadway: Lion King leaves a Phantom in the Dark

It’s early April and the height of the Broadway theatre season. Very quietly, a lion has run down a phantom – at the theatrical box office, that is. According to newly released figures, The Lion King had officially become the highest grossing show on Broadway, nosing ahead of The Phantom of the Opera. But these shows are starting to resemble fast-food production lines. By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

According to the numbers, the Lion was now $723,215 ahead in cumulative revenues from the dates when the two shows first opened on Broadway. The Lion King’s total take now stands at $853,846,062, whereas The Phantom has only made a meagre $853,122,847. And in the week ending with Easter Sunday, the Lion took in around $2 million, pulling ahead of a Phantom that could only claim a $1.2 million take. What makes it more interesting is that the Lion came to Broadway nine years after the other show started its run.

Nevertheless, The Phantom has been a major bonanza for its investors over nearly a quarter of a century. One such investor, James Freydberg, told The New York Times that when the show passed a major milestone he and his business partner invested $500,000 in Phantom because they thought they might possibly do better on Broadway than Wall Street after the 1987 Black Monday crash.

Since then, they have earned about $12 million from the show from its Broadway and national tours, and they are still getting regular $100,000 checks from a show Freydberg hasn’t been to see since opening night. Freydberg said about this investment decision: “No one ever, ever expected this kind of wealth. My only other investment that has performed better is my Apple stock.”

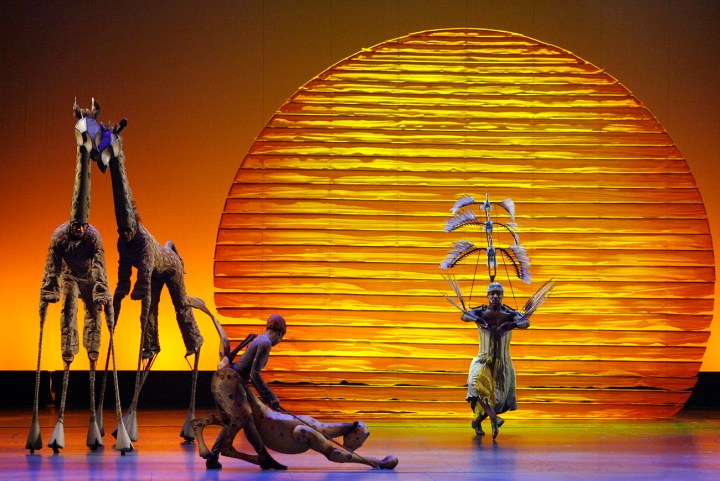

Popular music historian Cary Ginell, in analyzing the reasons behind the longevity of shows like The Lion King, said it’s very much akin to a Disneyland ride. “It’s a spectacle that satisfies on many different sensory elements: audio, visually, emotionally. It’s also good for all ages, just like Disneyland is. For the kids, it’s the visual elements: the colors, the costumes and the puppetry. For the adults, it’s Hamlet basically. And the music is not geared to one age or gender or race. It’s as universal a show as one can get.”

Well, maybe if Hamlet had stampeding wildebeest, Elton John music, and the circle of life. But the Disney experience is precisely what appeals.

Broadway has changed over the years. It is now inextricably tied up with broader entertainment trends. New York’s regular show-going audience has morphed substantially into an industry where out-of-towners and visitors rather than locals routinely fill the seats in the big shows.

Along the way, Broadway entertainment has become increasingly commoditised and integrated across the spectrum of other media and products, and the big shows become integral elements of international franchising and part of long-term marketing plans.

There was a time when the Broadway musical frequently had a significant literary pedigree and generally was a standalone venture that got its try-out in Philadelphia and New Haven. There it was tweaked and adjusted, and then finally put on to a Broadway stage. My Fair Lady began its life as a bit of Greek mythology that had been converted into a highly literate play, Pygmalion, by George Bernard Shaw, and then transformed by Lerner and Loewe into the musical, a show that held the record for decades for the longest continuous run on Broadway. There was Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents and Stephen Sondheim’s West Side Story, a work that reaches back to Romeo and Juliet. For decades, musical theatre drew on such literary and cultural antecedents, which brought the complicated textures of a powerful story to the resulting show.

But consider the new and former Broadway champion: The Lion King and The Phantom of the Opera. The former’s lineage traces back to a popular Disney feature-length cartoon, with a slight detour along the way to the popular South African song, The Lion Sleeps Tonight, as well as New Age philosophy about the circle of life and Mother Earth. While the latter does actually reach back to a once-popular 1911 novel by Gaston Leroux, in its current form it really owes much more to one of those Mills & Boone romantic, semi-chaste bodice rippers: beast-meets-beauty-loses-beauty story.

Photo: The Phantom of the Opera is based on a once-popular 1911 novel by Gaston Leroux.

Or as longtime New York Times drama critic Frank Rich wrote in his original review, it would be a “severe disappointment to let the hype kindle the hope that Phantom is a credible heir to the Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals that haunt both Andrew Lloyd Webber’s creative aspirations and the Majestic Theater as persistently as the evening’s title character does.

What one finds instead is a characteristic Lloyd Webber project, long on pop professionalism and melody, impoverished of artistic personality and passion. “The Phantom of the Opera is as much a victory of dynamic stagecraft over musical kitsch as it is a triumph of merchandising uber alles.” Careful, calculated merchandising, that is.

Both shows are still going strong on Broadway, on the West End, as well as appearing in a clutch of other cities around the world, including Cape Town and Johannesburg.

But the thing about these shows is that they are not independent, individual productions. Rather, they are cloned replicas – not a hair is different from one to the next. Once the original production’s team sets the next version in motion, local producers have to follow specifications and instructions hundreds of pages in length to make certain one production doesn’t vary by so much as a millimetre from the next one.

The audience expects to get the original show that has, somehow, been magically transported half way around the globe, lest they feel cheated. The highest praise comes when audiences can say, “it’s just like the West End version!”

In fact, if there is one thing that productions like these come the closest to paralleling, it is the fast food restaurant chain outlet. Go into a McDonald’s in Tokyo or Johannesburg or Des Moines, Iowa, and the hamburger will be – and it had better be – exactly the same thing, right down to the texture of the bun, the tang of the pickle and just the right squizz of mustard and ketchup. There is a huge manual for this too and secret inspectors check to make sure it is followed.

In fact, to watch The Phantom in Japan – or anywhere else with one of these franchise musicals – and the sole difference will be that the characters somehow have managed to learn to speak in fluid, colloquial Japanese while in the depths of the Paris Opera instead of speaking in their more natural English.

Productions like these are part of an intricate web of products and sales pitches that include DVDs and CDs, character dolls, children’s costumes for Halloween, authentic costume jewellery, children’s games, mugs, lunch boxes, toys, and other miscellaneous souvenirs. This draws impetus from the model pioneered by Walt Disney from the 1950s onward and refined further by the Star Wars empire of films, tie-in sales and a near-constant stream of products bearing the Star Wars imprimatur.

Central to the efflorescence of this kind of Broadway show from cartoon and comic book to live stage has been the sometimes-enigmatic presence of Julie Taymor. Taymor gets major credit for dragging the Disney cartoon tale of a lion cub forced to confront his inner and outer demons into being transformed into an engaging live theatre experience.

Taymor is something of an entertainment polymath, having directed opera and Shakespearean dramas as well as award-winning films. The “secret” engine of Taymor’s success actually lies in her experiments with the dance, drama and puppetry of Southeast Asia that combine high and low art simultaneously in these productions.

Taymor attended the Jacques LeCoq School of Mime in France and then apprenticed herself to the “guerrilla street-theatre-styled Bread and Puppet Theatre” of Chicago, which aimed at audiences well beyond traditional theatre ones with its avowedly political message in the 1960s and 70s. Then, having won one of those MacArthur Foundation “genius” grants worth about R5.5million, she spent years studying and performing in Indonesia, absorbing a Southeast Asian theatrical vocabulary that became the bedrock of her theatrical world.

Ironically perhaps, Taymor became the logical – perhaps essential – choice to transform a children’s cartoon into a multilayered, mystical theatre piece – on behalf of Disney. After this astonishing success, Taymor embraced the even greater challenge of turning the dark universe of Spiderman into another show, Spiderman – Turn Off the Dark.

The result broke Broadway records for the cost of the production, the number of previews before it finally opened, and probably the number of rewrites needed as well as the number of leads injured before the play even opened. Taymor ended up being released from the project before it had yet another re-conception, but the die has been cast. In the future, a safe prediction is that more and more shows will come out of the universe of the comic book and the cartoon for a very simple reason – audiences around the world both love this material and know and embrace its legends and leitmotifs.

As The Lion King neared its monetary milestone, Thomas Schumacher, president of Disney Theatrical Productions, said of Taymor that “her vision, continued commitment to the show and uncommon artistry account for this extraordinary success.” He added that the show keeps finding and attracting new audiences “millions of whom are experiencing their first Broadway show at The Lion King. Surely, introducing so many to the splendor of live theater is our show’s greatest legacy.”

In other words, people who never thought they would ever fork over a week’s wages to take their family to see a Broadway show continue to beat a path to the door of this one, and now they are going to line up to see Spidey as well.

Of course, The Lion King still has to catch up to the total number of tickets sold to Phantom, a show that has now run for more than 10,000 performances. In comparison, the Lion has yet to broach 6,000 performances and is only in its 14th year. Even so, it has made more money on Broadway than its more elderly competitor – and that is something that makes theatre operators and production house shareholders very happy.

On the larger, worldwide stage, however, The Phantom remains unique. Its producers and accountants say it is now the single most successful (profitable) entertainment effort of all time – with total revenues beyond those of Titanic, Star Wars and Avatar, pulling in over $5.6 billion, and with some 130 million people worldwide having seen it.

But the race is still being run between the two shows. The Lion King has seven – soon to be eight – productions worldwide, while Phantom has seven around the world, with shows on stage in London, New York, Hungary, Japan, South Africa, Las Vegas – and a UK tour as well, just in case getting into London is too much bother from the rest of the country.

Ginell points out that about 40% of the tickets to see Phantom are now being sold to people who have already seen it before – and nearly 70% are being sold to women. There it is, that Mills & Boone thing again. Ginell adds, “Phantom is kind of a live-action romance novel. I think that’s what’s attracting a huge percentage of women to the show.”

Or as New York Times critic Patrick Healy noted when the show was about to have its 10,000th performance on Broadway: “It is the musical that has come to define modern Broadway by proving the purchasing power of women and tourists, the durability of repeat business and the lure of spectacle: ingredients for success embraced by producers of The Lion King, Wicked, Mamma Mia! and other smashes.”

There is one local footnote that needs to be brought in right about here. When I saw The Lion King when it opened a few years back in Johannesburg, I noted that under the credits for the song The Lion Sleeps Tonight, George Weiss was still listed as the composer. This after a highly publicised effort had taken place to reassert the rights of the late Solomon Linda to be credited with composing that mega-hit.

A call to the producers quickly generated an “oops” and a promise to correct this in future runs of the programme – the baleful possibilities of negative publicity can become a powerful weapon, it seems.

Regardless of where these works fit on the scale of high versus low art, the sheer popularity of both works with audiences remains remarkable. During their first 750 playing weeks – a point recently hit by the Lion – they played to about the same number of audience members, about 10 million of them. Some theatre analysts say it is hard to predict when – if ever – the lights will finally dim for these shows.

As Ginell says of The Lion King, it “is the perfect family musical and I think it always will be as long as expenses don’t go so far up that they won’t be able to afford to put it on anymore.” That probably means you will be able to see it with your grandchildren, even if you are in your twenties. DM

Read more:

- The Lion King becomes highest grossing show on Broadway on CBS News.

- Phantom of the Opera (Frank Rich) in The New York Times.

- Cub Comes of Age: A Twice-Told Cosmic Tale in The New York Times.

- A Hit That Has Outlasted 10,000 Chandeliers in The New York Times.

- The Lion King the official website.

- Phantom of the Opera the official website.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider