REFLECTION

Alleged apartheid-era criminals must account – and there are many in happy retirement

The NPA’s decision not to prosecute two Security Branch officers implicated in the 1971 murder in detention of activist Ahmed Timol due to their ‘advanced age’ will certainly hearten other apartheid-era politicians and their minions now happily and unaccountably retired.

In October 2019, former Nazi SS guard Bruno Dey appeared in a court in Hamburg, Germany. He was 93. Dey was brought to court in a wheelchair to face 5,230 counts of being an accessory to murder.

The crimes Dey was accused of committing took place in the final years of World War II at the Stutthof concentration camp near Gdansk in Poland where the 17-year-old Dey had been a guard. More than 60,000 people – including Jews – were murdered there.

Almost 74 years after World War II, Dey’s trial is expected to be the last of the alleged Nazi war criminals.

The continued holding to account of individuals who commit crimes against humanity is an essential component in preventing future abuses of power by authoritarian or totalitarian states.

Apartheid atrocities still haunt the contemporary South African political landscape and the decision on 21 June 2020 by the American Bar Association to withdraw an invitation for FW de Klerk to participate in a series of interviews in the US on 1 July is evidence of this.

Objections from across the globe included journalist Lukhanyo Calata, son of activist Fort Calata, of the “Cradock Four”, assassinated in 1985.

Garson, and other young reporters from the independent Vrye Weekblad and the Weekly Mail found themselves in the thick of it in the killing fields collecting eyewitness accounts of third force and other covert activities.

The definitive 1998 Human Rights Commission publication A Crime Against Humanity – Analysing the Repression of the Apartheid, edited by Max Coleman, found that between 1948 and 1994, 21,000 people died in political violence in South Africa and Namibia.

The six-year transition in the country between 1990 and 1994 also exacted a high and bloody toll as documented in journalist Philippa Garson’s just-published Undeniable – Memoir of a Covert War.

Garson, and other young reporters from the independent Vrye Weekblad and the Weekly Mail found themselves in the thick of it in the killing fields collecting eyewitness accounts of third force and other covert activities.

But then, as now, the collection of illusive evidence prevented the flushing out of the powerful vested political interests.

At least 14,000 people died in the horrific spasm of violence during this period, stoked in part and in secret by Military Intelligence and other covert apartheid hit squads and third forces.

On 22 June 2020, the South African Coalition for Transitional Justice (SACTJ) issued a statement noting with “deep concern” the decision by the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) not to pursue charges against Security Branch police officers Seth Sons and Neville Els, implicated in the murder of teacher and SACP member Ahmed Timol in 1971.

In October 2017, Judge Billy Mothle ruled in the Gauteng High Court that Timol was murdered and that Els and Sons be investigated for misleading the court and that both should be charged with perjury.

But the NPA has cited the passage of 46 years in the matter as well as the advanced age of the two former policemen – 80 and 82 – as issues which placed the state in a “difficult position to prove that they were deliberately lying” in this instance.

Be that as it may.

Neither of the accused testified at the original 1972 inquest into the death of Timol, who died five days after his arrest – beaten and tortured and then flung from the 10th floor of police headquarters John Voster Square in central Johannesburg.

Du Plessis, now 80, emerged recently from quiet retirement in Pretoria on 12 August 2018 to demand an apology from the publishers of The Lost Boys Of Bird Island – an account by the late former policeman, Mark Minnie of his investigation into a paedophile ring that existed in Port Elizabeth in the 1980s.

The original inquest found that Timol had “committed suicide” and that “no person alive was responsible for his death.” Timol’s family has fought for over four decades to have the inquest reopened.

The SACTJ added that the Timol case had “great significance for the families of victims of unresolved cases of torture and murder during the apartheid period, and whose cases have been neglected for many years”.

In June 2019, 20 families of activists who were victims of apartheid crimes wrote to President Cyril Ramaphosa urging him to pursue justice for the dead and the murdered.

They urged the president to appoint an inquiry into alleged “pressure” on the NPA to drop investigations into the 300 apartheid-era cases the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had referred for potential prosecution.

The NPA’s argument in the Sons and Els matter, said the coalition, “If allowed to stand… will undermine the cause of justice for other outstanding cases such as those of the Cradock 4, the PEBCO case, Simelane, Bambo and many others which are before the NPA”.

The man responsible for issuing the order for the “removal” of two Cradock school teachers, Matthew Goniwe and Fort Calata – who were to become known as the “Cradock Four” along with Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli – was former apartheid minister of finance, Barend du Plessis.

Du Plessis, now 80, emerged recently from quiet retirement in Pretoria on 12 August 2018 to demand an apology from the publishers of The Lost Boys Of Bird Island – an account by the late former policeman, Mark Minnie of his investigation into a paedophile ring that existed in Port Elizabeth in the 1980s.

Minnie and journalist Chris Steyn spent 30 years on the story and while Du Plessis was not named in the book (former Minister of Defence Magnus Malan and former Minister of Environment Affairs John Wiley were), he claimed anyone reading the account would immediately recognise him and suspect he was implicated in the ring.

The book was withdrawn under pressure by Du Plessis, and an apology and a settlement were offered by Media24. Meanwhile, the Bird Island case has not been closed and is still being investigated by the SAPS.

In 1999, Guardian journalist Chris McGreal obtained minutes of that meeting. South Africa’s assault on Swapo in neighbouring Namibia was on the agenda, as was item five, which read “unrest in black schools”.

While Du Plessis might be of the view he would be identified in the book, many South Africans might have forgotten his key role in PW Botha’s government.

Du Plessis was the apartheid state’s money man and participated, at the highest level, serving as South Africa’s minister of finance between 1984 and 1992. He was also a member of PW Botha’s all-powerful State Security Council.

On 19 March 1984, 12 senior Cabinet ministers including Du Plessis, Defence Minister Malan and FW De Klerk, then minister of internal affairs, gathered for a Security Council meeting chaired by PW Botha.

In 1999, Guardian journalist Chris McGreal obtained minutes of that meeting. South Africa’s assault on Swapo in neighbouring Namibia was on the agenda, as was item five, which read “unrest in black schools”.

Du Plessis is recorded in the minutes as pointing out that two teachers in Cradock were “agitators” and that it would be “good if they could be removed” [verwyder].

McGreal reveals that “Two days after the council meeting, a security policeman, Jaap van Jaarsveld, was dispatched to Cradock with a colleague, Henry Fouche, to assess the best way of disposing of Goniwe and his colleague, Fort Calata.”

On 27 June 1985, Goniwe, then 38, as well as Calata and two other anti-apartheid activists, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli – today remembered as the Cradock Four – drove to Port Elizabeth for a meeting.

En route, they were abducted by apartheid security police and brutally assassinated. The bodies of Mkhonto and Mhlauli were found on a dump near Bluewater Bay while Goniwe and Calata were found in the bay a few days later.

In an August 1990 interview with scholar Padraig O’Malley, Du Plessis recalled these horrific events differently, of course.

O’Malley suggested that Du Plessis and other senior Cabinet ministers must have known about the murder of Goniwe and other activists at the time.

“All they had to do was to read the newspapers and they would have known something funny was going on.

“Nine people in two weeks don’t slide on a bar of soap and disappear out of the window of John Vorster Prison. At least somebody might say what kind of soap are they using?” O’Malley asked.

To which Du Plessis replied, “For instance, Goniwe, I remember Goniwe gave us a lot of trouble in my 10 months as minister of black education, but I knew that he was a good teacher and I knew that he was politically very active and so on.

While the case of the Cradock Four is one of 15 cases being investigated, the family had, Calata told Daily Maverick, given the NPA until 10 July to respond.

“I think then what they did, the general came to me and said, ‘Minister, this guy is causing such trouble, we want to get him out of that area. We want to transfer him to another school. Take him out of that political environment and see if we can still use him as a teacher.’ And I would approve that kind of thing.”

The brutal slaughter of the Cradock Four made world headlines and a massive funeral attended by thousands was held. On that Du Plessis was silent.

Lukhanyo Calata and his wife Abigail have written about the murder of his father in My Father Died For This, published in 2018. In the book, Calata called for those who were responsible or party to his father and his comrades’ death to be prosecuted.

While the case of the Cradock Four is one of 15 cases being investigated, the family had, Calata told Daily Maverick, given the NPA until 10 July to respond.

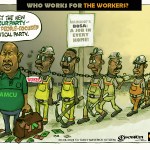

The NPA, the SACTJ said this week, had a “constitutional obligation to pursue” outstanding cases but had “repeatedly neglected this duty largely due to political interference as stated in court papers explaining its failure to act”.

Victims’ families had had to pursue justice without state assistance and on their own.

The NPA’s reasons, the lapse of time and the failing memories of the accused, were “manifestly spurious” said the SACTJ.

The Supreme Court of Appeal it said, had upheld the conviction of tennis icon Bob Hewitt for the rape of two young girls, crimes that had been perpetrated in the 1980s. In that instance, Hewitt was 75 when convicted and sentenced to 37 years and the court held that while age might be a “mitigating” factor it did not act as a “bar to a sentence of imprisonment”.

Joao Rodrigues, the now 81-year-old cop accused of murdering Timol, has attempted to dodge accountability by pleading age and infirmity.

It has been confirmed that the apartheid state incinerated 44 tons of evidence in industrial furnaces in the lead-up to SA’s first democratic elections in 1994.

This much been highlighted in research by author and scholar Jacob Dlamini, in his magisterial just-published The Terrorist Album – Apartheid’s Insurgents, Collaborators, and the Security Police.

Dlamini writes that this purge of its misdeeds, this “paper Auschwitz”, had been a conscious effort by the apartheid state to “deliberately and systematically destroy a huge body of state records and documentation in an attempt to remove incriminating evidence and thereby sanitise the history of oppressive rule”.

In the case of the Bird Island matter, there is no dispute that PW Botha personally ordered Minnie’s investigation of the paedophile ring to be removed from his office in Port Elizabeth.

The destruction of paper evidence unmoors an event from its intrinsic truth. In the end, it is the living testimony of those who were there and who are still alive which helps to reconstruct and understand it.

Calata on 22 June 2020, with regard to FW de Klerk’s cancelled visit to the US, said that the last apartheid president had a case to answer for his alleged role in crimes committed while he was in senior leadership,

“It is critical that De Klerk and all other apartheid criminals are hauled to court soonest to be held accountable. The ANC government’s failure to hold them accountable has emboldened them to a point where they even denied that apartheid was a crime,” said Calata. DM