BOOK EXTRACT

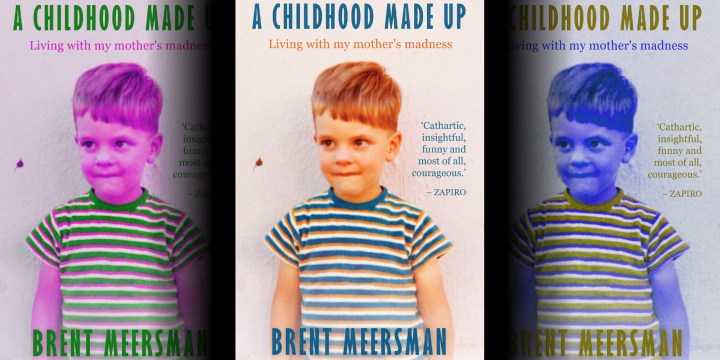

A Childhood Made Up: Living With My Mother’s Madness

This is an extract from Brent Meersman’s poignant memoir of a humble and eccentric upbringing in Cape Town, South Africa, in the 1970s and ’80s. His adoring mother, a horse-loving artist, received only rudimentary treatment for her schizophrenia, while his father battled a vicious whirlpool of alcohol-fuelled depression.

I was going to jump, but I wasn’t sure I had the nerve or that the flats were high enough to end it outright and not leave me a lingering cripple, living with the humiliation of a failed attempt. I began by jumping from the first-floor landing at the back of the block, where nobody was likely to see me, and there was a thick, green lawn to land on. This was quite a drop for a 12-year-old, but I would land like a British paratrooper, remembering to bend my knees to absorb the fall and then to roll my body. That wall became the suicide equivalent of training wheels on a bike.

I started by hanging with my fingertips to make the drop as short as possible. Then I began to jump straight off the wall. The first time it hurt. I lay on my back on the grass staring up at the blue sky. On days when the clouds were wispy and ever-changing, I would think of something I’d like to see, such as a dragon or a fish, and the white kaleidoscope above would quickly oblige. Some of the creatures I saw appeared to be falling to earth. Faces were always plentiful, as they were in my mother’s watercolour paper. I wanted to be there – swimming with the woolly dolphins in the clouds.

The next time I was in an unbearable emotional state but refusing with all my being – that I would not be reduced to tears, that I would not cry – I went up to the first floor almost as if sleepwalking and jumped without hesitating. I nearly broke my knees. The pain did not deter me. It felt good. I went up to the second floor and looked down; definitely not high enough. I went up to the third floor. I got one leg over the balcony wall. My other leg, still grounded on the landing, was trembling. Hey, diddle, diddle! . . . The cow jumped over the moon. Best I fall head first to make sure. I closed my eyes. What if my legs instinctively swung under me like a cat’s and I spent the rest of my life broken and in a wheelchair? What if I changed my mind halfway down? The horror of it. What if I landed on some poor innocent person who stepped out at precisely the wrong moment?

I had a thought: I could do away with myself at any time; it didn’t have to be today. I’d wait. I would know when things were really, truly, awfully unbearable. I would do it then. I could go on another day. I had the power to decide.

Then fate intervened to make sure. On one of my reconnoitres to the third floor, I was trapped by the two teenaged thugs who lived in the block. They were the local bullies, twice my size and almost out of high school. They had tried to catch me several times before. Now they had me. I was so terrified of them I can’t recall their faces, except that they were fleshy and their bodies unfeeling and impervious to my blows. I punched with all my strength. I thought I broke my wrist. But I had no effect on them. They grabbed me by the arms and legs. I screamed and kicked, trying to wriggle loose from their grip. They laughed to have such fun. Then they held me over the balcony saying they were going to drop me. In my panic, I kept on wriggling and screaming. Had I managed to kick those bullies loose, I would have dropped like a stone and hit the tarmac three floors below. And they would have learned what it felt like to kill someone.

Maybe they went on to become apartheid security policemen dangling communists by the ankles out of windows at John Vorster Square police headquarters.

They left me lying on the cold cement of the landing, a jellied mess, my crotch all wet – the only time I have ever peed my pants from fear.

But they had cured me from thoughts of jumping, at least for a while. I no longer ventured upstairs in case they were around. I resorted to chewing the inside of my cheek or my bottom lip until I could taste blood. Nothing heals faster than the mouth and nobody can see the wounds inside.

Decades later, when a good friend’s fourteen-year-old son committed suicide, I avoided her. I knew she had plenty of support from her large family, but that was not it. It was my own past I couldn’t confront, not her and her grief, but my thoughts of suicide when I was a child. I felt deeply ashamed.

My family remained clueless about my inner turmoil. Academically, I was an overachiever. My teachers couldn’t have been happier with me. My parents didn’t know that every achievement at school was tainted with embarrassment. My uniforms were hand-me-downs from my brother and usually in poor condition. My school blazer had cuffs that were threadbare and worn and I tried not to wear it, even when I was freezing. I made pathetic attempts to clutch my cuff with my fingers to hide the frayed end and to keep the lining in that was falling out. My hand would develop a cramp after a while.

Prize-giving ceremonies were a bore for many of the other children because I was there collecting all the silver cups and gold certificates. Being covered in gold didn’t stop me feeling inferior. The audience had no idea I was trying to hide my shame and my blazer cuffs as I stretched out my hand to pick up my prize, that I was dying inside fearing the principal would notice my scuffed shoes and not understand that even polish couldn’t save them any more.

My mother’s horror of needlework meant that when pockets had to be sewn back on or holes stitched up, the mending was obvious for all to see. And nothing could be done about a frayed collar.

Fortunately, there were a couple of other poor kids in the class, so I wasn’t completely alone. We didn’t band together in solidarity, though; we didn’t really like each other. Nasty comments were few, but I felt separated from most of the other kids by my family’s poor circumstances and I struggled to belong. Sometimes I couldn’t participate in school outings because we couldn’t come up with the fee.

Mom hated the fund-raising school cake sales and the expectation of her to bake something. She’d buy the cheapest cake on the supermarket shelf and my fruitcake or Madeira log would be the last thing left on the trestle table at the sale. The school often made requests for money or items to bring to class and I was sometimes the only one who hadn’t complied. It was horrid to be treated as rebellious when you were in fact just poor. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider