ROBERT MUGABE’S DESTRUCTIVE LEGACY

Game’s over for Mugabe, but not for the country he helped devastate

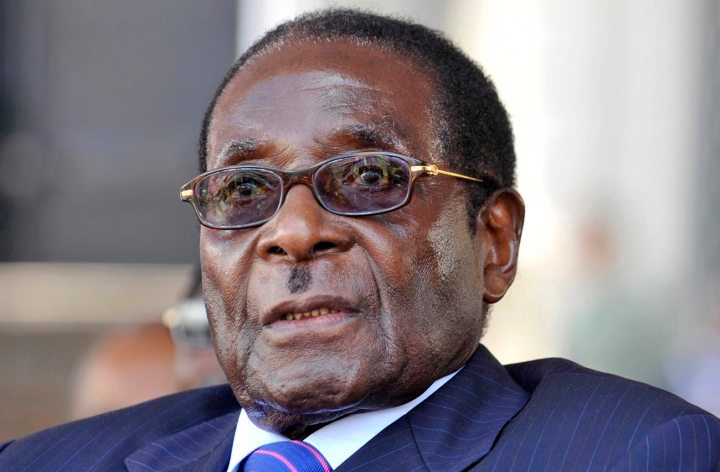

With the passing of Robert Mugabe at the age of 95, the evaluations and re-evaluations of his legacy have begun. Start right here.

Back in the mid-1970s, a political scientist friend asked me if I wanted to visit Rhodesia with him to get a sense of the political dynamic and possibilities in the country ruled by Ian Smith’s breakaway, pirate regime. At the time, of course, American diplomats were generally not supposed to travel to Rhodesia except in extraordinary circumstances. Accordingly, I asked my superiors if I could take the trip, thinking a first-hand, low-level view of developments might be useful to the State Department. Unfortunately, they rejected my proposed road trip, so I never did see what the country was like, pre-independence.

Rather, for my background at the time, I relied on the writings of social scientists, artists, historians and reporters, and occasional conversations with South Africans familiar with the country. I even spoke with a few (both black and white) who had moved north, rather than continue living in a South Africa, then in the tight grip of Verwoerdian-style apartheid, whenever those people were back in Johannesburg on family visits. That was then; but, 15 years later, things were rather different.

In the late 1980s, I spent a week in Zimbabwe at a gathering of American diplomats. Fortunately, it wasn’t all conference rooms and meetings. We had various chances to get away from our meetings each day. There were concerts to attend, art gallery openings to join in, and drives out of town to see various development efforts supported by foreign aid programmes, although I unaccountably missed the day trip to Victoria Falls.

A colleague very familiar with Harare led several of us to a pleasant restaurant with rather good food. The restaurant’s wine list proudly displayed the output of a number of local vineyards, and the four of us in our dinner party all concurred; our choice had an astonishingly rich taste, but redolent of turpentine spirits and pine tar. It was poured from a bottle – and I swear I am not making this up – that proudly bore its varietal name: “Cabinet Sauvignon”. The local beer was a much better choice.

The next day, on a solo city walk, I encountered a street with the paving all torn up. The inevitable thought crossed my mind, “Well, there goes the neighbourhood, the city, and the country. Here’s the evidence, right underfoot.” But turning the street corner on my ramble, instead of still more decay and destruction on view, I came across a work crew energetically replacing broken paving with new materials, as they worked towards repairing the street I had just turned away from.

Throughout my various walks and other encounters, admittedly not deep into the countryside, or with very many disaffected people, I always felt real warmth from the Zimbabweans of my interactions. I definitely felt no rancour towards white people, or with foreigners more generally, for that matter. Instead, as a person coming from the south, always watching events unfolding in South Africa’s ongoing agonies that seemed to be careening towards a racial cataclysm, late 1980s’ Zimbabwe seemed like a model of a possible better future: If South Africa could just embrace a transformation in the manner of Zimbabwe, especially after their bitter civil war/war of liberation, it would be a miraculous outcome indeed for South Africa and its people.

And, of course, in the centre of that transformation was Robert Gabriel Mugabe, now the undisputed master of Zimbabwe. Leading the Zanu-PF into negotiations with Ian Smith’s regime and the British government (still the ostensible colonial power under international law), Mugabe was elected overwhelmingly as the country’s new leader, following the full transfer of power to an independent state in 1980. Initially, he had seemed to demonstrate a real interest in building a unified, economically prosperous nation that could inspire the rest of the continent – and most especially its still-white-ruled neighbour to the south.

Espousing a spirit of reconciliation, Mugabe had said:

“The wrongs of the past must now stand forgiven and forgotten … If yesterday you hated me, today you cannot avoid the love that binds you to me and me to you.”

Importantly, however, he had added an ominous warning that later gained more serious import. If “the open hand of reconciliation” was rejected, he said, it may “turn into a clenched fist”.

This view on reconciliation, of course, should also be weighed against the ethnic repression against the Ndebele of Matebeleland in 1983-87, carried out by the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade in which tens of thousands of civilians were butchered, and where the current president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, had had a major role in that grisly work. Similarly, he began to elbow out other Zanu-PF leaders from the actual bush war, as well as Zipra’s Joshua Nkomo, a figure whose party and the other movement had also played a significant role in the country’s eventual liberation.

What is without question, however, is that Mugabe led a government that made real strides in massive improvements in public education and public health. The enormity of this effort, in turn, encouraged teachers, medical personnel, engineers and other professionals from around the world, in the West and Africa, to come to this new Zimbabwe to be a hands-on part of the building of a new nation.

In economic terms, despite the fighting, the Mugabe government had inherited a solid, forex-earning agricultural economic base, including extremely high-quality tobacco and various agricultural staples. There was also a curiously thriving industrial sector – based in part on entrepreneurial flair in evading or overcoming a range of sanctions against trade with the then-Rhodesia. But, early on, market conditions were favourable for Zimbabwe, and international investors such as food processing giant Heinz joined in this new enthusiasm as well.

For someone like Petina Gappah, the international lawyer, novelist (and later, briefly, an adviser for the administration that followed Mugabe’s in 2017), but who had been a primary school pupil back in 1980, has said:

“By the end of the [first year of her university academic year], I had studied constitutional law, and learned, through case law on illegal detentions, that all the time I had been gulping down books as a child in the library, a state of emergency had been in place in Matabeleland, and that region had been the theatre of mass killings by the army’s Fifth Brigade.”

She added that she now recalls of one of her teachers in school and the growing unease she came to feel …

“Mrs Nleya, a teacher I loved, who was trained in England and returned to Zimbabwe at the promise of independence, but died when the one oncologist in her city closed his practice, and moved to Botswana.

“Or the many who died of conditions easily cured but for the shortage of drugs.

“Or the border jumpers, almost all of whom were born after 1980, the Born Frees who drowned in the Limpopo on their way to South Africa, and hope.

“The companies small and large, built up over years of hard work that collapsed under the weight of inflation. The livelihoods flushed away, the lost opportunities, the cheated dreams.

“Was it all so that one man could rule until his death, so that he could, as opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai said so poignantly, destroy not only what he had inherited, but also what he had built himself?

“Thirty-seven years after he promised that we would all build a Great Zimbabwe – but did everything he could to destroy it – Mugabe has left the stage.”

This leads to the thought of what would have happened if, similar to Nelson Mandela, like George Washington, or like Roman general Cincinnatus, Robert Mugabe had elected to stand down after leading his nation for a decade. If, instead of insisting on hanging on for 37 years, he had deliberately nurtured a cadre of dedicated, well-trained individuals ready to take over the leadership of Zimbabwe, and, as the national father figure, had retired to a well-earned rest and the justifiable admiration of his people. Had that happened, it is plausible to imagine circumstances where Mugabe could well have been the continent’s senior liberation figure, helping guide change inside South Africa – as well as in Lusophone Africa, for example, where dreadful civil wars were continuing to devastate entire nations.

Instead, apparently angry at the breakdown of agreement internationally over the financing of an agricultural landownership transformation programme, Mugabe unleashed the seizures and confiscations by the war veterans (including at least some who would have been toddler soldiers) of much of the land still held by white commercial farmers, ostensibly for a radical land reform process. Inevitably, perhaps, in a growing climate of corruption and official avarice, many of those once-thriving farms ended up in the hands of an elite surrounding President Mugabe, including members of his own family.

Inevitably, too, in order to finance the government and its projects, the Mugabe regime fell back on the tried and true method of foolish regimes – the untrammelled printing of money and thus the thorough devaluing of the currency. Eventually, Zimbabwe surpassed the agonies of the German Weimar Republic as the local dollar became essentially worthless, and as the only currencies people could use for their expenditures became the dollar, euro, pound or rand. The Zimbabwe dollar, with notes denominated in the trillions, were being printed, but no one wanted to be stuck with them.

Not surprisingly, this financial chaos had devastating impacts on trade, domestic commerce, investment, finance, and banking. (As anyone with Zimbabwean emigre friends or employees knows, the many hundreds of thousands, indeed, the millions of Zimbabweans working outside the country have all tried to accumulate as much of those hard currencies as possible, along with bags of staple foods, to send home or to carry back themselves in order to keep their families going.)

In the midst of this rolling disaster, there were still elections, and despite strenuous government efforts to break the opposition, the Movement for Democratc Change – the MDC – was finally brought into a contentious coalition government with Zanu-PF, giving the MDC’s Morgan Tsvangirai a largely symbolic place at the table – after being severely beaten up for his troubles.

Now, return to that idea of alternative history. If Mugabe had elected, then, in the late 2000s, to make a stately move to a permanent leisure under the shade of those vast subtropical trees on the grounds of one of his villas, now with his second wife, Grace, by his side, then his place in his country’s history as one of its primary liberators and father of the new nation, albeit by then a tarnished reputation, might still have endured. But he did not. Again.

Instead, he held on for a decade further, as the economy of Zimbabwe continued to degrade (even if some studies are now pointing to upticks in agriculture among a class of emerging black Zimbabwean commercial farmers) and the country had become substantially dependent on foreign food aid. Eventually, after days of demonstrations by ordinary Zimbabweans, the military made its move and a clearly disoriented old man read a barely coherent statement that signalled his surrender to reality and the weaknesses of aged flesh. His legacy, in the words of veteran South African editor Mondli Makanya, was:

“The Zimbabwe that Mugabe created , as he became more and more paranoid, is a repressive securostate where the military, the police and intelligence services are the real government.”

For the ordinary Zimbabwean, forced to come to South Africa to support a family, their resigned response probably echoed a Zimbabwean acquiantance who said, simply, “He was old. He died. It’s over for him.” But not, sadly, for the country he helped devastate.

A final irony for me in thinking about the now-late former Zimbabwean president was that for the past several months, Mugabe was in a private hospital in Singapore, Gleneagles, where he had been treated for cancer. I know this hospital well since our first-born child was born there, delivered by an emigre South African Chinese doctor. Wonderful hospital, great care.

But the care for Mugabe and the costs for his family and aides and hangers-on to stay in Singapore for all that time must surely have taken a real whack out of Zimbabwe’s scarce forex reserves, and, in the end, will probably end up representing a measurable share of the country’s enfeebled national health budget. It has all been such a shame and will take so much effort to repair the damage done. But one final act remains – where to bury the former president, how the government will position itself regarding his funeral, what should happen to his widow, and, of course, what will happen to any wealth he may have amassed during his 37 years in power. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider