One of the last attempts of new cities in the apartheid framework was Botshabelo, between Bloemfontein and Thaba Nchu. In the mid- Seventies Connie Mulder and his apartheid planners announced that they were developing what would become “a model city in Africa”.

After the decision to relocate the Sesotho speakers from Kromdraai in Thaba Nchu (in the then Bophuthatswana) to Onverwacht where Botshabelo was developed, attempts to lure businesses to the area commenced. Factory shells were built and rented out at a tuppence as part of a range of incentives to lure “industrialists” to the industrial park. One of the erstwhile “successful” industries was operated by a Taiwanese who had 30 industrial washing machines in a 1,400sqm building. His factory was stone-washing of imported jeans from Taiwan to achieve the popular worn-out effect before exporting them. And he farmed with wage subsidies under the decentralisation scheme as well.

Today the industrial park is about 80% occupied but not by manufacturers, rather warehousing. The majority of Botshabelo residents who are employed work in Bloemfontein and commute daily. The illogically (that is what ideological decisions turn out to be) placed town requires several thousand to commute daily: Expenditure of time and money that could have made a major difference in the livelihood of poor and lower-middle-income households were they located closer to their places of work.

Botshabelo stands in stark contrast to other new towns that came into being in the pre-democratic era: Sasolburg, Vanderbijlpark and Richards Bay. These were not attempts at building cities, but to get internationally competitive businesses of substance going. The development of core businesses spurred the relocation of other enterprises to these localities and also the formation of new businesses, either in the direct value chain or simply to service the local consumer needs of the growing population in these towns. Urbanisation and growing towns in these localities were the results of exporting industries, not vice versa.

It is important to note that the government did play a significant role in these developments: At that stage, Iscor (Vanderbijlpark) and Sasol (Sasolburg) were state-owned enterprises. In the case of Richards Bay, the harbour development and the dedicated coal railroad were massive public-sector investments in port and rail infrastructure. However, the Sasol factory was almost from the beginning supplemented by British investments (for example, the Fisons fertiliser plant) and several other private sector investments. A similar story unfolded in Richards Bay with Triomf fertiliser, the Alusaf smelter, Bell Equipment and later on Mondi and numerous others.

The contrast between Sasolburg, Vanderbijlpark and Richards Bay as new economic hubs on the one hand and Botshabelo as an ideological “dream city” on the other, is there for all to see, provided one sheds one’s ideological blinkers.

The growth or decline of a city or town is determined by the flow of money into or out of the locality. Enterprises are important generators of income, but the largest percentage of enterprises are mainly aimed at servicing local consumer needs, therefore feeding primarily off money already in the locality. The Enterprise Observatory of SA, EOSA refers to such enterprises as run-of-the-mill enterprises. The majority of businesses belong to such categories.

Apart from traders, businesses in the enterprise sectors of construction, financial services, engineering and technical services, general services, telecommunication, health services, real estate, media & promotion services, health sector services, personal services as well as logistics and transport services, are predominantly run-of-the-mill enterprises.

Ricardo Hausmann reckons the abundance of productive knowledge is the key factor in successful countries and a shortage thereof the main reason for failing economies. The same holds true for cities and towns.

Productive knowledge, far more than infrastructure or run-of-the-mill enterprises, determines the well-being of cities and towns. The availability of productive knowledge enterprises based on real market demand and not ideological subsidies is the dividing factor between Richards Bay and Botshabelo.

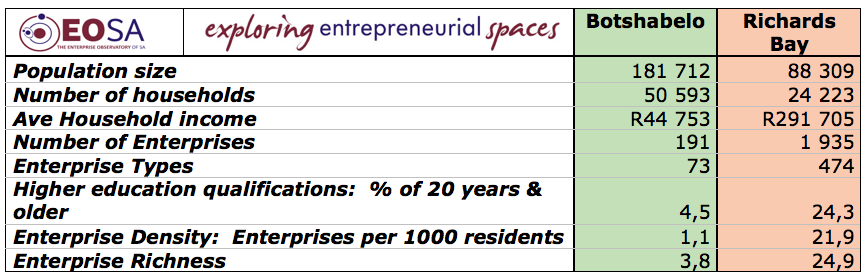

Richards Bay developed into what it is, not only because of the capital that was invested in the infrastructure, the harbour and the factories. Its human capital, measured (in this case) by the % of the population over 20 with a tertiary qualification, drives the difference.

In addition, the Enterprise Density is 21.9 compared to the 1.1 in the case of Botshabelo. The Enterprise Richness (measuring enterprise differentiation) of 24.9 is 6.5 times more diverse than the 3.8 of Botshabelo.

Successful cities and towns differ from failing cities and towns. In both cases, there can be population growth, but successful cities do not only attract people, but they also grow connectivity with external markets and diversification of products and services.

Productive knowledge is not in abundance. Countries, cities and towns that want to grow should do their utmost to create conditions that are enterprise-friendly, otherwise they will not be able to grow their pool of productive knowledge. In fact, they run a risk of having that base eroded as is currently the case with South Africa.

None of these fundamental aspects has been mentioned in either the dreamy SONA address of 20 June, nor in the response to the debate. That places the envisaged skyscraper city in concept closer to Botshabelo than to Richards Bay. It could even be worse than Botshabelo…

The South African economy is not waiting for a new city. It needs sound policies, not a fine-tuning and we-will-manage-the-same-better-than-before approach. That is needed today, not tomorrow. The President in his surreal SONA speech, as well as his response to the debate, did not indicate a willingness to cross the Rubicon. Like PW Botha before him, he chose a prolongation of the recent current.

PS: The examples of China’s city growth is not simply replicable in the SA context. China experienced accelerated urbanisation in the post-Mao era when the technological innovation of computerisation and digitisation took off, enabling the country to skip some of the more conventional phases of infrastructure roll-out and industrialisation, moving in numerous industries directly into a service mode. In addition, in 1990 China was only 26% urbanised, way lower than South Africa at that period. Even now South Africa is a more urbanised country than China where the figure now stands at 59%. Rapid city development is necessary when 330-million people urbanise over a period of 40 years. DM

Johannes Wessels is head of the Enterprise Observatory of SA.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider