Business Maverick, Politics

Analysis: Is South Africa over-banked?

One of the many voguish catchphrases of the past few years has been the notion that South Africa is “under-banked”. But look at the stats and it’s hard not to draw the opposite conclusion – that SA is a dangerously “over-financialised” economy.

For years, the notion that SA is “under-banked”, in the sense that too few people have access to bank accounts, has been a political clarion call. Under this “access to banking” banner has flown a whole new raft of financial innovations, including new rules which allowed micro-finance organisations to flourish and which forced banks to offer new, cheap accounts.

But do these innovations actually help? Or did they just put millions of people in a position where they are constantly fighting to keep debt under control?

This applies in SA at a micro-level. But it applies at a macro-level too, and not just in SA, but in the developed world as well. And regulators and academics are beginning to wonder whether it’s not more of a problem than a solution.

The same sorts of questions that apply at a micro-level in SA apply on a macro-level all over the world – and apply now with so much more force following the implosion of American and European banks in 2008.

There is no doubt that financial innovation can help and that banking services for the poor are necessary, but is it a lasting solution or just a temporary balm? Can a society be “over-banked”?

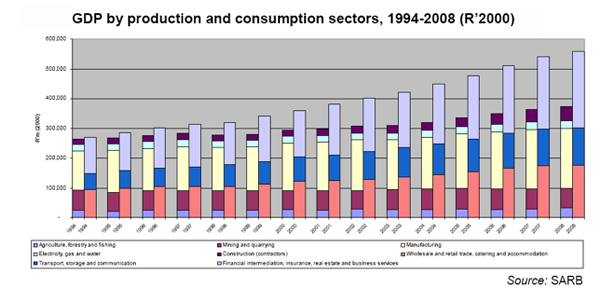

According to the SA Reserve Bank, in 1994 the “financial intermediation industry”, in other words banks, insurance companies, business service organisations and related industries, constituted about R100 billion of SA’s GDP of R500 billion in 1994 in constant 2000 rands. (This is different from current GDP because inflation since 2000 has been stripped out: SA’s GDP is currently $276 billion on a nominal basis and $500 billion on a purchasing power parity basis.)

The financial industry has grown hugely, and now constitutes about R250 billion of SA’s R900 billion economy in 2008 in the year 2000 numbers. In other words, it has more than doubled in size in real terms and now constitutes roughly 28% of total GDP compared to the 20% it constituted in 1994.

But the real key to understanding what has happened is not to look at banking, but at retail and telephony together, the other two big growth sectors: they have also gone from a bit more than a fifth of the economy to being about a third. Simple conclusion: banks have lent people more money and they have spent it on cellphones and new stuff from the mall.

Government’s new Industrial Policy Action Plan document describes this as a “structural problem”, but looks to improving manufacturing to redress the balance. The document says “growth has been driven by unsustainable increases in credit extension and consumption not sufficiently underpinned by growth of the production sectors of the economy”.

This problem at the micro-scale is now attracting substantial critics at the macro-level too. The New York Times’s Economix blog recently published a profile on Adair Turner, head of Britain’s Financial Services Authority, written by Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Simon Johnson who wrote that Turner had “developed a flair for pushing the official conversation on banking forward”.

Photo: The Chairman of Britain’s Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner. REUTERS/Andrew Winning

He spoke in favour of a tax on financial services long before that was fashionable, and the idea that was subsequently picked up by a host of different governments which imposed new taxes on bankers, Johnson writes.

But his big idea is that much of financial innovation is not actually socially useful – and might, in some instances, be profoundly dangerous.

This seems obvious now following the US and European banking crisis, but it goes further. At something called the 14th Chintaman Deshmukh Memorial Lecture, delivered at the Reserve Bank of India in Mumbai a week ago, Turner pointed out that the so-called Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 and the more global crisis of 2008-9 had much in common.

According to the New York Times, both were rooted in, or at least followed after, sustained increases in the importance of financial activity relative to real non-financial economic activity, an increasing “financialisation” of the economy.

Turner argued that the dominant conventional wisdom of economic theory and policy – the Washington Consensus, as it was labelled – has assumed and asserted that this increase in the financial intensity of the economy is beneficial, driving a more efficient allocation of capital, imposing discipline on inappropriate policies and enabling investors and users of funds to hedge risk better.

“But this theory has been shown to be severely deficient, failing to take account of the inherent potential of financial markets to be subject to self-reinforcing herd and momentum effects, with periods of irrational exuberance followed by sudden and contagious panics.

“Short-term capital flows can, under some circumstances, be harmful: and complex financial innovation in developed countries has produced few demonstrable benefits and resulted in an increased risk of financial instability,” he told the lecture.

Turner’s arguments have been made before and constitute part of a challenge to the free market ideology, echoing ideas expressed by scholars such as Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Subramanian.

Yet the question is whether these ideas are simply reactive to a recent disastrous economic event or whether they constitute part of a serious new direction in economics?

At a macro-level, the problem is that financial institutions are not only much larger as a proportion of the whole economy, but that they are linked together so strongly that they are like mountain climbers on a cliff all tied together. If one falls off the cliff, he can drag all the others down with him.

This problem affects the situation at a micro-level too. The event that causes one bank to fall off the cliff is the failure of a whole raft of smaller loans and advances.

The key is to make sure that the level at which the banking industry expands is in proportion to the expansion of the economy as a whole, and not, as has been happening over the past decade, faster than its ability to climb the precipice safely.

The problem is particularly acute for South Africa which had a big financial sector to start with and is now getting larger. If South Africa continues in this direction, it seems possible that the financial sector will increasingly crush the sectors of the South African economy it’s supposed to serve, with increasing desperation about how to cycle cash within the local industry rather than use it to generate productive capacity within the country.

By Tim Cohen

Main photo: Reuters