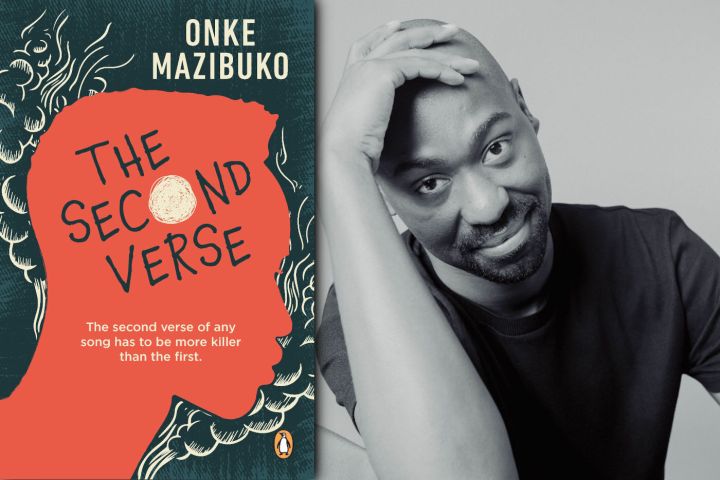

Book Excerpt

Onke Mazibuko’s debut novel ‘The Second Verse’ is a humour-laced coming-of-age story

In his debut novel, Mazibuko looks at South Africa’s ‘missing middle’.

East London, 1998. When Bokang Damane, who attends a predominantly white boys’ college, writes a school essay on suicide, everyone thinks he wants to kill himself. Meanwhile, family finances are floundering – his parents can’t even afford his initiation into manhood – while his alcoholic dad is spiralling out of control. Then he meets Nokwanda.

“This is a coming-of-age story for anyone who has ever tried making sense of life while living in conflicting realities, and trying to pretend that completely losing it isn’t the most inevitable outcome,” Onke Mazibuko says of The Second Verse, his debut novel.

“Manhood, and especially the traditional constructions of it from a Xhosa perspective, are explored through the eyes of a teenager. These are weighed against the constructions of manhood from an affluent all boys’ college with strong western influences,” he says. He believes The Second Verse will speak to all those “who have had to straddle the line between different cultures, who are aware of how their beliefs and values are influenced by worlds that often seem in conflict.” Here is an excerpt.

***

Mr Knowles’s suit looks like it’s made from the same material as a seatbelt – cheap, dark-brown and faded – probably as old as he is.

‘Bo-gang. Talk to me.’

He looks at me as if I owe him something. After all this time at this school, and still this fool can’t say my name right. No surprise. They all like this.

‘Look, Bo-gang, I’m here to help you. This is about what’s best for you. I can’t help you if you won’t speak to me.’

Right. The only thing that matters to him is the school’s reputation. He cares about me about as much as a butcher cares about animal rights. His eyes give him away; the stretched skin under one of them twitches.

He waits.

Silence is golden and patience is a virtue. Let’s do this thing, then.

His office really sucks for a deputy principal’s. It’s not much of an office actually, but then again, he’s not much of a deputy either. I bet the head and the other deputies laugh at his punk ass. Punk-ass Knowles. That’s what they should call him. His office is all the way at the back of the school, in the dead zone, where nobody ever goes. There’s barely enough space for the two of us in here, with his long legs and all. The walls aren’t even the same colour, and it stinks of boiled cabbage and old newspapers. Ten bucks says this used to be a cupboard or something.

Someone’s stupid laugh comes from outside: loud and carefree. Other boys out there enjoying their break-time, while I’m stuck in here, dealing with this petty nonsense.

Mr Knowles holds up the essay. ‘Help me understand this, Bo-gang, please.’

He must think he’s talking to one of his sorry-ass kids when they step out of line. So lame. ‘Sir, I don’t know what to say.’

‘This essay is, well … what can I say? Shocking, to say the least. Don’t you think?’

‘It’s just an essay, Sir.’

‘Just an essay? No, Bo-gang. This is … a lot more, I think.’

He can believe what he wants. This fussing is way overboard. I actually thought I did pretty well on this one.

‘You’ve written here about suicide, Bo-gang, in great detail. We’re concerned about you.’

Why can’t this damn chair swallow me whole and save me from this grief? Punk-ass Knowles, with his punk-ass questions. Best for me? What the hell does anyone know about what’s best for me?

Mr Knowles goes on to ask me questions about my school subjects. I tell him. He asks me about my teachers. I tell him that, too. He asks me about English and my teacher, Ms Hargreaves. I tell him what he already knows.

He wipes his hand across his spotted forehead. ‘Talk me through this essay. Why suicide?’

‘It was the topic, Sir.’

‘No. The task for Ms Hargreaves’ essay was to design a project to address any social issue. You chose suicide. Not as the social issue, but as a solution.’

The man has interesting books on his shelf, the titles running along the spines. One of them is really thick: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It’s like a bible of the things psychos suffer from, I bet. Probably has mad-parables and verses of the ins-and-outs of insanity, people’s shortcomings and suffering, definitions of oddballs, treatments for the marginalised and normal run-of-the-mill shamefaced losers. But what does it say about the society that created them?

‘People should not be stopped when they want to kill themselves,’ Mr Knowles reads from my essay. ‘They should in fact be encouraged.’ He looks up briefly before continuing. ‘Every person has the ability to make decisions. This should be respected. Suicide is a person’s prerogative. People should not say it is a wrong act or a cowardly decision. People should not even say it is a brave decision. It is only a decision, made by a person for themselves.’ His eyes trail out the window. He turns back to me with an expression I don’t get. ‘What are you really trying to say here?’

‘Maybe you should read the whole thing, Sir.’

‘I have, and I must say, I am not only appalled, but greatly disturbed.’

Trust Mr Knowles not to get it. ‘I thought shrinks weren’t supposed to be judgemental, Sir.’

Mr Knowles’s brow drops. He tries a smile, but his clenched jaw undermines any friendliness he might be trying to fake.

‘Bo-gang.’

‘My name is Bokang, Sir.’

‘Bo-kang. Look, as I have said to you already, your well-being is our greatest priority. You must appreciate the fact that you’re part of this exceptional college, and everything that affects you affects us too. I’m trying my level best to ensure an amicable outcome for everyone concerned.’

Yeah, right. And I’m Bishop Tutu.

Back to the waiting game, then. Shrinks are supposed to be good with that. Mr Knowles seems to be struggling, though. He checks his watch, then the clock on the wall. He sits back in his chair, his foot resting on his knee, revealing a hairy shin the colour of mozzarella cheese.

‘Okay, fine. We have informed your mother. We don’t want misunderstandings; by giving you an opportunity to talk, we hoped to avoid any further unpleasantness. But if—’

‘Sir, it was just an essay, honestly. Suicide is not such a big deal, when you consider other areas of society that need attention. As I said in my essay, suicide can be used to generate income to solve problems.’

‘How exactly?’

‘Well—’

The bell rings. It sounds like the damn thing is right inside this office. Mr Knowles smiles like he’s used to it, like his ears and eyes aren’t about to bleed. The sound stops, but something still rattles in my ear. Voices and footsteps get louder as boys move towards the buildings. What a shame, it’s such a dope day to be outside.

Mr Knowles is saying something.

‘Sir?’

‘I said, you don’t have to go back to class right away. Your mother is on her way, and I think it best we reach some sort of conclusion, and consensus, on where we stand, before she gets here.’

‘Suicide clinics, Sir. The world needs lots and lots of suicide clinics.’ Mr Knowles lifts an eyebrow. ‘Imagine if, for a hundred bucks, a person could go to a clinic and be put down peacefully. No mess. No trauma. Perfect for the family. All the person’s affairs put in order before they die. Right?’

Mr Knowles stares at me.

‘All the depressed people out of the way, and they pay for it. I mean, it’s their decision to die, right? And for a good cause. Think of the numbers, Sir.’

Mr Knowles rubs his chin.

‘Imagine all those hundreds of rands. That’s mad-cash, Mr Knowles Sir, by anyone’s standards. And the world is already overpopulated, right? Now we solve that problem too.’

‘Bo-gang. Bo-kang, I don’t think—’

‘I’m just saying, it’s a win-win situation. So many problems solved. Imagine what we could do with the organs of all those dead people, Sir. Think of the long-ass organ transplant lists out there—’

‘That’s enough!’ He wipes his forehead again. ‘Surely you know that suicide – the taking of one’s own life – is morally wrong?’

‘I’m not so sure about that, Sir.’

He clears his throat, his Adam’s apple flexing like a knuckle. ‘Might I remind you, Bo-kang Damane, that this is St Stephen’s College, an institution with a great history and strong traditions. It is incumbent upon you to speak in the proper manner, as you have been taught, and as expected of you as an ambassador of the school. Arguing and cutting me off is highly unbecoming. You might also want to mind your language when addressing a senior staff member. I don’t need to tell you that.’

‘Yes, Sir. Absolutely.’

Punk-ass Knowles.

He lectures me about the morality of suicide and Christian values and the school’s expectations and blah blah blah.

The phone on his desk rings. Mr Knowles ignores it for the first couple of rings, then answers with his eyes still on me. I can’t hear the person on the other side. Mr Knowles nods and speaks in short sentences. ‘Well, it seems your mother is here. Let’s take a walk to Mr Summers’ office, shall we?’

It takes us less than ten minutes to get to the principal’s office, where his secretary, Ms Tudhope, a woman who reminds me of a white-headed vulture, ushers us in. Ma is already there, grinning awkwardly at something Mr Summers has just said. Poor Ma, she don’t need this drama. Everything’s been blown way out of proportion. Mr Summers, with his I’m-scared-to-get-old hairstyle, tells me to wait outside his office while the grown-ups talk.

Ms Tudhope won’t stop eyeballing me. I swear if she keeps it up, I might just bust her a good one in the beak. She picks up the phone and starts squawking.

A kid walks in. Ms Tudhope points him to a seat with one of her talons. He slouches in the chair with his hands pumping into each other. His grinning face is an explosion of zits, as if he downs a huge smoothie of steroids every morning for breakfast. I don’t make eye contact, even though I know him. Well, I don’t know-him-know-him, but I know of him. Everybody knows Randall Leonard. And everybody knows that Randall Leonard spends more time in the principal’s office than any other kid. He’s been in the school just over a year, he’s two grades below me, and yet he has one hell of a reputation. Now they got me up in here with Randall Leonard, like we ‘Delinquents R Us’ or something.

Twenty minutes later, the door busts open and Mr Knowles waves me in. Now this is an office, not like that shoebox Mr Knowles works in. This one is worthy of a man like Mr Summers, who sits behind his perfect desk, with his perfect hair and his perfect teeth. Ma and Mr Knowles sit in chairs next to each other in front of the desk. I’m offered one on the other side of Ma. She still hasn’t looked at me.

Mr Summers addresses us like a man used to an audience. He explains what Mr Knowles told him about our little chat, and what the three of them have discussed. It doesn’t sound like Mr Knowles sold me out too badly. Words like ‘concerned’, ‘well-being’ and ‘effort’ fly around the room. The old lady studies him with blinking eyes.

‘Thank you, all,’ Mr Summers says, ‘for pulling together to ensure the well-being of Bokang. Mrs Damane, I applaud you. Your effort as a parent is appreciated.’ He gives her a politician’s smile. Turning to me, he says, ‘So, Bokang, we are all in agreement. For your well-being – and considering the context your mother has just shared with us – you will see Mr Knowles for at least three more sessions …’

Oh Lord.

‘… redo Ms Hargreaves’ essay …’

Christ on a bicycle.

‘… and write an extra essay on morality.’

Strike me down now, Lord, please.

‘Okay, Bokang?’

‘Yes, Sir.’

Back outside, walking towards the school gates, Ma keeps up a mean pace. I feel like I used to as a toddler following her in a supermarket when she was fed up with me. Why would she be fed up with me now?

It isn’t until we’re in the ride and the school is out of sight that Ma finally says something. Typical: she’s concerned about what people will think. She waits for the traffic light to turn red. ‘You know how far away my work is, my child?’

‘Yeah, Ma, I know.’

‘And still I have to come out here for this.’

What does one say to that?

‘You know I can’t be doing this, Bobo. I’ve got too much work.’

‘I know, Ma. But it isn’t what you think.’

‘What do you mean?’ She grips the steering wheel with both hands. ‘Tell me. What is all of this?’

‘There’s no problem. It was just an essay.’

‘I saw it. It was embarrassing. Do you really want to kill yourself?’

‘No, Ma.’

‘Then what?’

‘The light is green, Ma.’

‘I don’t care about the light!’ Somebody behind us hoots. ‘Go to hell!’

It’s not every day you hear the old lady cussing. This is bad. But tough titty. It’s not my fault everyone is losing their damn minds.

She pulls off and I’m sitting here wishing I was in another place, in another time, and in another life. Good God, the D.R.A.M.A! The stupidity of it all!

Ma takes the off-ramp onto the North East Expressway from Pearce Street towards Beacon Bay.

‘What is it you want me to do for you?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Do we need to take you back to Dr Schultz? My medical aid is used up, but—’

‘Definitely not.’

‘At least they said you can see the psychologist at the school.’

‘Yeah, thanks for that. Why’d you have to go and tell them?’

‘Everyone is trying to help you.’

‘Trying to help me? They’re making a big deal about nothing. No, I don’t want to kill myself. No, I don’t need to see a psychologist. I’m fine! Sheesh! Why can’t you just get that?’

‘Bobo, we don’t want this to be like last time.’

‘This is not like last time! I’m fine, Ma. For real.’

It’s a quiet-ass ride to Beacon Bay, which suits me just fine. We drive over Batting Bridge; the murky waters of the Nahoon River beneath are dull like the sink water in an art class. A dude on a speedboat causes ripples across the surface. I wonder what his problems are, and how they ripple into the rest of his life.

Ma makes a stop by KFC to grab some grub. She knows it’s my favourite, so I guess this is some sort of peace offering. She can barely afford these takeaways.

We pull into the driveway to the crib. Ma doesn’t open the garage door. Instead, she switches off the engine and places a hand on my arm. She removes it when I stare at it.

‘You know I love you?’

I don’t say anything.

‘You can always talk to me.’

Yeah, that’s what everybody keeps saying.

She turns towards me and takes my hand in both of hers. ‘Do you remember when we used to go to Bonza Bay? On Sundays, just the two of us? We’d get up early to catch the sunrise, but we’d always miss it.’ She laughs, but it isn’t a pretty sound. ‘Do you remember, Bobo?’

‘Yeah.’

‘It was so lovely. Do you want to go there? Now?’

‘Nah, Ma. It’s okay. I’m good.’

‘Come on, Bobo. It will be like old times.’

I pull my hand away.

‘Bobo, your teachers gave me your essay. It’s in my bag. We can forget this whole thing. Your father doesn’t need to know. We’ll be quick.’ She starts up the ride.

‘Okay, whatever.’

But our progress back down the driveway is halted by another ride pulling up. The back doors open and my younger siblings, Israel and Sizwekazi, tumble out, all smiles and giggles. Ma switches off the engine.

I grab my school bag and head into the crib.

Yeah, so much for old times. DM/ ML

The Second Verse is published by Penguin Random House (R320). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

In case you missed it, also read Chilling and intriguing: Joy Watson’s debut novel, The Other Me

Chilling and intriguing: Joy Watson’s debut novel, The Other Me

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9591″]

Comments - Please login in order to comment.