ANALYSIS

Rwanda’s rhinos are safer than its dissidents

Rhinos are being relocated to Rwanda in an effort to establish a breeding stronghold in East Africa. The Kigali government’s iron fist will likely shield the pachyderms from poachers. Human critics of the government, however, are a different matter. They still face extermination.

Rwanda’s rhinos are safer than its dissidents. This speaks to a discomfiting facet of wildlife conservation in Africa: it has a human rights problem.

Many conservationists will take umbrage with this assertion and, in fairness, they are caught on the horns of a dilemma. Much critical wildlife habitat in Africa is located within the borders of repressive, corrupt or failing states. To preserve biodiversity, greens play with the geopolitical cards at hand.

Mountain gorillas, for example, are only found in the Virunga mountain range straddling Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Uganda and Rwanda. The species’ fate is in the hands of a crumbling, corrupt and conflict-riven state in the case of the DRC, an autocracy in Uganda’s case and a sinister police state in that of Rwanda.

Conserving these remarkable apes requires a handshake with the devil. Many conservationists have made this pact.

But some lines do not have to be crossed. Translocating wildlife to countries with appalling human rights records perpetuates negative perceptions regarding such initiatives in Africa.

Among these is the damning view that Western conservation NGOs and their backers are more concerned about the plight of Africa’s animals than that of its people.

The historical record is strewn with many examples of rural Africans forcibly removed to make way for wildlife reserves, and colonial and apartheid policies that placed animal welfare before that of people.

And the stench of the colonial past still hangs in the air.

WWF and other wildlife-focused NGOs have been accused of backing highly militarised anti-poaching campaigns that target not just alleged perpetrators, but communities, with evidence of crimes including murder.

A 2020 report cleared WWF staff of complicity but raised red flags about lack of oversight. And the slaying of Cecil the lion in Zimbabwe by a US trophy hunter in 2015 triggered a global outcry that stands in revealing contrast to the muted response that greeted a murderous campaign in the 1980s in the same region which saw the slaughter of 22,000 Africans.

Against this backdrop, Rwanda’s rhinos serve as a microcosm around these issues, the complexities involved and the point that choices are available.

Rhinos rewild Rwanda

The NGO African Parks announced in November 2021 that it had undertaken the largest single rhino translocation yet. Thirty white rhinos were relocated from the Beyond Phinda Private Game Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa to Akagera National Park in Rwanda.

Funding was provided by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, which has become a cheerleader of note for all things Rwandan.

“This historic initiative aims to extend the white rhino range and create a secure new breeding stronghold in Rwanda, supporting population growth to ensure the long-term survival of the species in the wild as high levels of poaching continue to exert unsustainable pressure on current populations,” African Parks said when it unveiled the translocation.

On the surface, this has the makings of a wildlife success story.

“Rewilding” — restoring wild flora and fauna to former landscapes, or providing new ranges and strongholds for endangered species — is an important environmental movement, one with deep historical roots which is gaining a lot of traction.

The five species of rhino left on the planet are in a jam, poached relentlessly for the alleged medicinal benefits derived from their horns.

White rhinos are by far the most numerous, with the vast majority in South Africa, where their numbers on state reserves have been in sharp decline for more than a decade in the face of the poaching onslaught to feed horn demand in fast-growing Asian economies.

By contrast, white rhino populations on private reserves in South Africa have been growing. Most of South Africa’s roughly 12,000 to 13,000 white rhinos are now in private hands under (apartheid-era) legislation that allows for game ownership.

This gives the private sector a leading role in the preservation of the species and rewilding efforts.

There is no recent recorded history of white rhinos in Rwanda. But Akagera has been the scene of other successful wildlife translocations involving lions and black rhinos, species which have historically called Rwanda home. This can be seen as rewilding in action.

“The introduction of southern white rhinos to Akagera expands their range to offer more safe area for the species,” African Parks noted.

“To ensure that this new population of white rhinos also flourishes, each rhino has been fitted with a transmitter to enable constant monitoring by dedicated tracking teams; a canine anti-poaching unit and helicopter surveillance are also in place to provide further support for their long-term protection.”

The rhinos will also enjoy the protection of the Rwandan state, which, to put it bluntly, you don’t f**k with. It’s a ruthless totalitarian state — one that hunts down and kills dissidents at home and abroad, including in South Africa, where the rhinos originated.

The most high-profile example was that of Patrick Karegeya, once Rwanda’s head of external intelligence, who was found murdered at the beginning of 2014 in a posh Sandton hotel room.

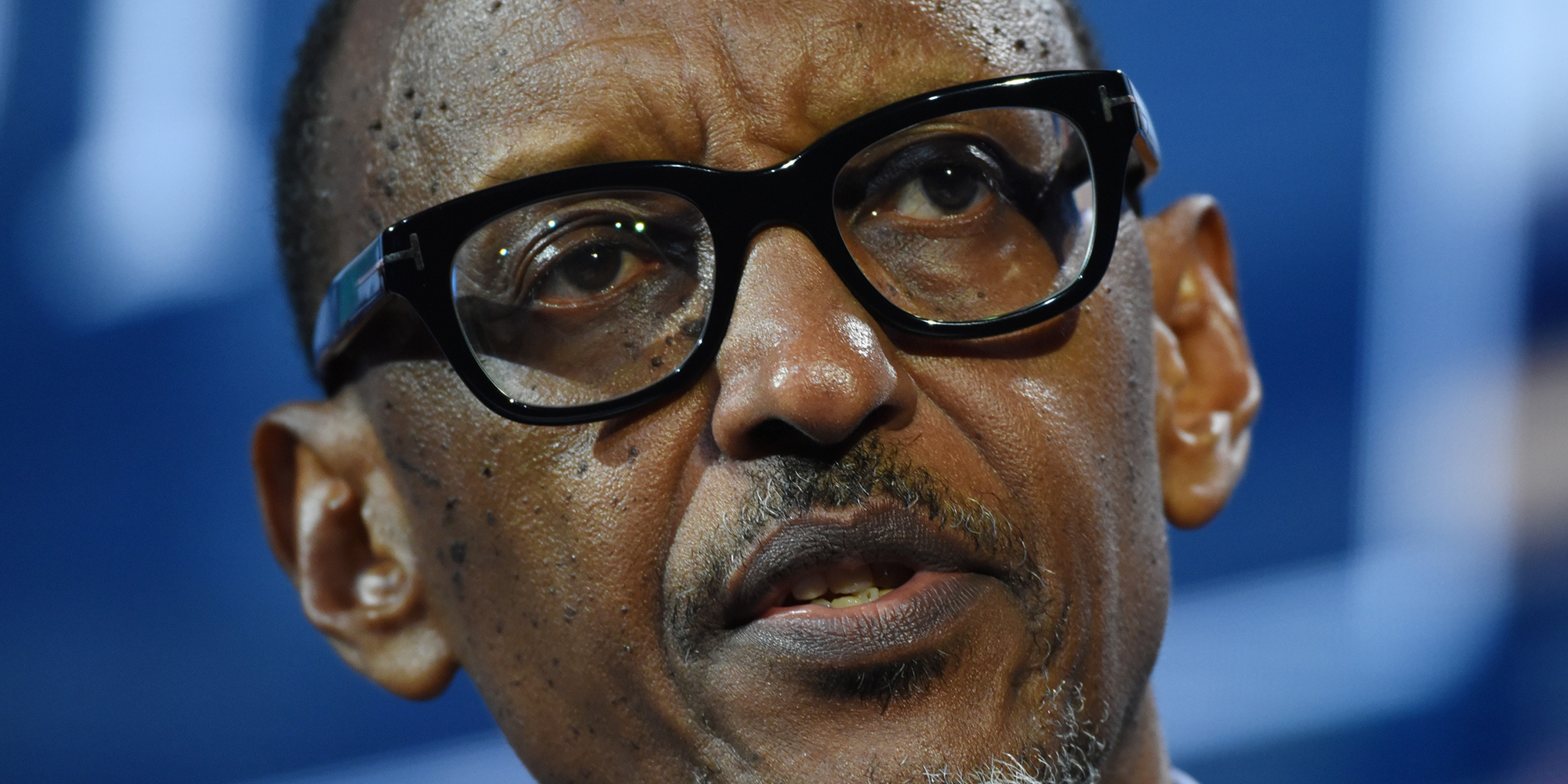

President of Rwanda Paul Kagame. (Photo: Riccardo Savi / Getty Images for Concordia Summit)

The diabolical nature of the Rwandan regime under President Paul Kagame has been clinically dissected in veteran journalist Michela Wrong’s troubling 2021 book, Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad.

This is a government that tolerates no dissent, allowing it to thread unopposed a narrative depicting a deceptive pattern of economic success that Western donors and investors have risen to like a ravenous trout after a mayfly.

“Do Not Disturb” was the sign placed on the door of the room where Karegeya was slain, a fitting metaphor for the approach outsiders have generally taken to Kigali’s tyrannical disposition.

While rhinos get a new lease of life, it remains open season on Rwanda’s human dissidents. A March 2022 report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) makes this abundantly clear.

“Rwanda has very few opposition parties, and human rights organisations and independent media remain weak,” the report notes.

“Victoire Ingabire, who was the president of the unregistered opposition party FDU-Inkingi before founding Dalfa-Umurinzi in November 2019, was released from prison in 2018. Members of her party have repeatedly been harassed, threatened, and arrested, or have died or disappeared in suspicious circumstances.”

On its Rwanda Country page, HRW says: “The ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front continues to target those perceived as a threat to the government. Several high-profile critics have been arrested or threatened and authorities regularly fail to conduct credible investigations into cases of enforced disappearances and suspicious deaths of government opponents.

“Arbitrary detention, ill-treatment and torture in official and unofficial detention facilities is commonplace, and fair trial standards are routinely flouted in many sensitive political cases, in which security-related charges are often used to prosecute prominent government critics.

“Arbitrary detention and mistreatment of street children, sex workers and petty vendors occurs widely.”

This is surely a cause for concern for donors, investors and NGOs — including those in the wildlife space.

Is this a government that conservationists or philanthropists, such as the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, really want to embrace?

Supporting conservation initiatives in such a country is, after all, a signal of support for the government, which craves stamps of foreign approval along with donor funds. It adds further threads to the dubious narrative of success — another ribbon-cutting ceremony for officials representing a murderous government.

Rescuing rhinos also tugs at the hearts of affluent Western suburbanites, who often have cliched views of Africa and its wildlife, informed by Disney films and Tarzan. It’s a perfect target for the Rwandan government, which has mastered the fine art of manipulation.

“What I find really impressive about the Rwandans is how they identify what matters to the West, and then they drill down on it and they deliver on it. They are incredibly skilled at doing this,” the author Michela Wrong told me in an interview.

“For example, I don’t know how many times you will see that women’s representation in the Rwandan parliament will be cited approvingly across the world, especially in the industrialised North, as a sign of a progressive government.

“The issue with that is that Rwanda’s parliament has little power and none over big, strategic decisions. It’s an absolute trope. But it forms part of this extraordinary manicuring and sculpting of Rwanda’s reputation and image abroad.”

Banks light the way with coal

But Rwanda’s rhinos rub uncomfortably against the grain of another emerging trend — one that has taken the corporate world by storm and which many NGOs claim to embrace.

ESGs — environmental, social and governance concerns — have taken centre stage in the world of finance and investment. Rwanda’s rhinos may tick the E box to a certain extent, but collaboration with such a menacing regime raises uncomfortable questions around the S and G boxes.

A big part of the ESG equation is risk to reputation, and this can stem from association.

Take banks and the coal industry. Because of fossil fuel’s links to climate change and pollution, a growing number of banks are no longer funding new coal projects.

The coal sector’s obituary remains premature, as recent events have highlighted, but the writing is on the wall as it is slowly starved of capital. This development has been driven by investors, the wider public, government policy and also, pointedly, NGO campaigning.

So there are precedents for choosing what assets or industries to embrace, and there is no reason why this cannot be applied to countries based on their governments — or indeed any partner.

You get judged by the company you keep. And international finance has signalled it no longer wants to keep company with coal. Environmental NGOs, to their credit, have played a role in this ongoing divorce of capital from coal.

If coal makes green NGOs see red, one would hope that flagrant and brutal human rights abuses would as well. An agenda that claims to be progressive should uphold standards across the ESG board.

I asked African Parks and the Howard G. Buffett Foundation questions on this matter. Both organisations — which do commendable work on a range of fronts — have probably not encountered questions framed in this way before. As this story went to press, neither had responded to my queries.

This is a pity because their association with Rwanda clearly exposes their reputation to risk — an issue worthy of scrutiny and debate. The G in ESG is about governance after all, so it can be applied to governments.

This brings us back to the matter of agency.

Are there alternative destinations to Rwanda for South Africa’s rhinos? And in the grander scheme of things, is Rwanda critical to rewilding efforts involving endangered African megafauna?

Sixth extinction knows no borders

A case could be made that, given the gravity of the ecological crises defining the Anthropocene — notably biodiversity loss and climate change — conservation initiatives to arrest these trends must be undertaken wherever possible, regardless of a state’s human rights or governance record.

The preservation or regeneration of habitat for wildlife adds to biodiversity while creating carbon sinks that mitigate climate change, or renewed landscapes that replace ecologically damaging activities such as cattle farming.

Rewilding efforts such as those taking place in Rwanda are part of this package. A “sixth extinction” is unfolding, and it knows no borders.

Rwanda is also Africa’s most densely populated country, so its rewilding projects can be regarded as test cases.

If Rwanda can reintroduce large, dangerous animals to its territory, surely it can be done elsewhere. And finding safe havens for rhinos in multiple locations is regarded as critical to the securing of the animals’ future in the wild.

It’s also the case that there are plenty of other suitable candidates to advance the cause of rhino restoration.

These include states that may not be pristine examples of governance but are far more democratic than Rwanda, which admittedly sets an extremely low bar. Ghana, Botswana and Zambia come to mind, but the options need not be limited to Africa.

One of the many wider goals of the rewilding movement is to restore megafauna to former ranges in the Americas or Europe. Many large mammals, including rhinos, went extinct outside Africa during the Pleistocene. A growing scientific view is that this was a consequence of overhunting by humans, which is why it marks the start of the Anthropocene.

A mountain gorilla in the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda, 05 October 2012. (Photo: EPA / Gernot Hensel)

The broader point is that choices can be made, and that tiny Rwanda is hardly crucial to the wider goals of megafauna conservation — with the exception of mountain gorillas, by dint of biogeography.

But there is a lot of available habitat elsewhere where rhinos can roam.

Akagera is only 1,122km2 — South Africa’s Kruger National Park is almost 20 times bigger and, while it is the focal point of the poaching crisis, it is still probably home to the world’s largest concentration of rhinos.

Botswana and Zambia, among many other options, have far more space, which raises further question marks around the choice of Rwanda, where “land hunger” is a serious issue.

Indeed, the 1994 genocide was partly rooted in conflict over land. If and when the regime of Kagame, a Tutsi, falls, what are the prospects for Rwanda’s rhinos?

Critics may note that a place such as Zambia would have obvious capacity issues when it comes to rhino protection, and fair enough. But it’s surely a slippery slope to suggest that wildlife conservation in Africa requires some variation of fascism.

The Rwandan model of governance is in some ways a mirror of colonial and apartheid governments which relied on brute coercion to “keep Africans in line”.

South African rhinos have also been transplanted to Chad and eSwatini, states that, like Rwanda, have highly questionable credentials when it comes to human rights.

The private sector reserves from which these animals have been sourced hold the keys to the preservation of white rhinos.

As alluded to above, most of the world’s white rhinos are in the hands of private South African game ranchers and future rewilding projects involving the species will be drawn from this stock.

Such private custodians of the species could also draw a line in the sand and say, in future, they do not want to send their animals to countries like Rwanda.

So could NGOs and donors. African Parks and the Howard G. Buffett Foundation are hardly alone when it comes to wildlife conservation initiatives in states that trample on human rights.

And the issue goes beyond Africa — many environmental NGOs work in countries such as Russia.

It must be said that many of these organisations do important conservation and scientific work, as do African Parks and the Howard G. Buffett Foundation. That does not mean questions cannot be raised about their choice of government partners.

And in the case of Rwanda’s rhinos, the optics are quite jarring, bringing the broader picture into sharp focus.

A human population is being bludgeoned into submission, while relocated rhinos roam freely in habitat that is not even crucial to their survival.

Depriving Rwanda’s regime of rhinos will do little harm to the cause of megafauna conservation, while sending Kigali a powerful message: you don’t get to play such a role on the environmental — or E stage — when your social and governance — S and G — standing is so transparently odious.

It would also signal that wildlife-focused NGOs and their backers care about human rights in Africa, and put the needs of people ahead of the conservation requirements of animals.

South Africa’s rhinos can go elsewhere to escape the poacher’s bullets.

Rwanda’s dissidents, by jarring contrast, have few places to hide from a predatory state that regards them as prey. DM/OBP

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9419″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.