EXPLAINER

The real deal with renewable energy in South Africa — unpacking the suite of options

With COP26 under way in Glasgow and multiple discussions under way about climate change, renewable energy sources and a just transition, it can be a confusing world out there.

When I started hearing about renewable energy in South Africa, I thought it was fairly simple — renewables are better for the environment, SA has great resources for it, it’s becoming cheaper and cheaper.

But then, I fell rapidly into the valley of despair (see the “Dunning-Kruger effect” graph below).

The more people I spoke to and the more I found out, the more confused I became and the less confident I felt.

The more people I spoke to and the more I found out, the more confused I became and the less confident I felt.

The one thing I did understand was, things were more complex than I initially thought.

With the rest of the world transitioning to renewables, the recent R131-billion finance deal at COP26 with developed nations to help SA transition to cleaner and renewable energy sources, and the urgent need to cut our emissions as we steadily warm toward 1.5°C (the “tipping point”) — renewables seem to be something we should understand.

Are renewables really the cheapest form of energy?

Professor Roula Inglesi-Lotz, the first president of the South African Association for Energy Economics (SAAEE) says, “it is sometimes unfair that renewable energies are all accumulated into one as the technologies are completely different to each other and as they provide different benefits and different throwbacks.

“So I would say a statement that renewables overall are better or worse or more cost-effective or not than coal might be a generalisation.

“On the other side, renewable technologies including the development of technologies for the generation of energy from solar, wind, or hydro have been improving for many years now; something that makes the costs definitely decrease and be more comparable to coal.”

Bertha Dlamini, founding president of African Women in Energy and Power, had similar thoughts.

“We cannot draw a linear comparison between renewable energy sources and coal-fired power plants. We need to examine the role of each technology in each energy mix that is tailored for a country’s economic needs.”

But she did acknowledge that “the cost of renewable energy technologies has been declining as the demand is growing globally”.

Electrical engineer and energy analyst Chis Yelland said: “My view is that when it comes to procuring new generation capacity, we should be looking carefully at the least cost option that meets the socioeconomic objectives that government set.”

Yelland explained that government has the socioeconomic objectives of creating jobs, using less water and to meet a certain trajectory in terms of CO2 emissions, because of their commitments to the Paris Agreement.

Dlamini agreed: “The South African energy sector should move away from an either/or approach to an integrative thinking approach that will design a mix of solutions suited for our economic and social needs.”

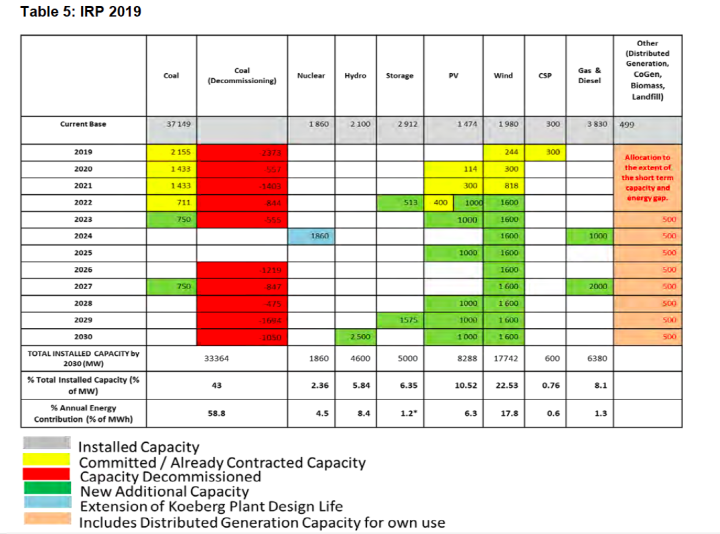

The Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), which last came out in 2019, predicts how much power we will need in the next 10 to 20 years and runs a least-cost scenario to determine what combination of energy will provide the country with a reliable and least-cost electric service.

The IRP uses software called Plexos to determine the least-cost energy mix, which is the same software that the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE), the CSIR, many governments, electricity utilities and research bodies around the world use for integrated resource planning.

“It’s a sophisticated model, it uses different technical characteristics of various technologies: coal, nuclear, wind, solar, etc,” explained Wikus Kruger, a research fellow who deals with power sector investment in Africa at UCT’s Graduate School of Business.

“You input cost assumptions around these technologies, you set specific parameters around the reliability that you need, so for example, how much redundancy do you need in the system, how much margin for error is there, and you can also include stuff like greenhouse gas limits.”

Kruger said that the model used in the IRP found that the least-cost solution is a combination of solar photovoltaic and wind technology plus a flexible generation source (like gas to power or battery storage).

Yelland agreed that one of the least-cost options, which will also meet the socioeconomic objectives the government has set and meet the criterion of a certain level of reliability of supply, is the combination of renewables and flexible generation. However, Yelland also said that another low-cost option is to extend the life of Koeberg Nuclear Power Station by another 20 years.

However, the final IRP has been criticised for restricting renewables, including more gas than necessary (see Karpowerships) and commissioning 1.5GW of new coal-fired power plants.

“It runs a least-cost scenario, and it gives you the cheapest power,” Kruger explained, “then it goes to the DMRE and they policy adjust it, meaning that they restrict the amount of renewables that can go into it — basically forcing nuclear and more gas than is needed.”

Yelland said: “Unfortunately, this is now where the politicians come in. And unfortunately, in South Africa and other countries, there’s a whole lot of commercial and other vested interests that want to influence the outcome of this techno-economic study.”

Kruger said that while the IRP includes more mandates for gas and coal than necessary, the least-cost scenario is still clear — renewables are cheapest.

In support of this, the latest results of the Preferred Bidders for Bid Window 5 of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP), announced on 28 October 2021, illustrates how the cost of renewables is increasingly low and cheaper than coal.

Kruger said: “Renewable energy is cheaper than coal. It’s definitely cheaper than building new coal and that we’ve known for a while, but what this round (REIPPP bid window 5) is showing us, is that it’s actually cheaper to build renewables than to keep some of our more expensive coal plants running.

“And it’s not just cheaper than running those coal plants. Many of these IPP projects are actually cheaper than just buying coal. So it’s a massively different landscape than it was before.

“The problem we have now is that we don’t have enough power, so we need to keep those plants running, otherwise the lights go out.”

In a virtual seminar last Wednesday, organised by the UCT Graduate School of Business’s Power Futures Lab to analyse the results of this latest round of renewable bidding, Bernard Magoro, the head of the DMRE’s IPP office, discussed the winning bids.

The lowest wind project in this window came at R0.34 per kilowatt hour, and the highest price for wind projects was about R0.62.

For solar PV, the cheapest bid was R0.37 per kilowatt-hour and the most expensive was R0.48 per kilowatt-hour.

Magoro said: “It’s very, very encouraging that for the first time, in fact, wind came out cheapest of the two technologies.”

The average cost of renewable energy projects in Bid Window 5 is R0.473 per kilowatt-hour.

Kruger explained that this price includes all costs of building the infrastructure, operation (delivering power to Eskom’s grid) and maintenance (for 20 years).

Additionally, Hein Reyneke, general manager for Africa at Mainstream Renewable Power said during the webinar that what they’ve seen is a global trend of long-term value of renewable plants beyond the first 20 years.

“We fundamentally believe that post the first 20-year procurement process or once a PPA (Power Purchase Agreement) is terminated that these assets will still operate and also be able to sell energy to the market,” said Reyneke.

Now compared with the price for coal IPP, renewables are cheaper.

An August 2021 report by the Energy Systems Research Group (ESRG report), titled “Assessment of new coal generation capacity targets in South Africa’s 2019 Integrated Resource Plan for Electricity” found that new coal power is more costly compared with alternatives.

Using data from the last REIPPPP bid window in 2015 (as this study came out just before Bid Window 5 results were announced) and the Coal Caseload IPP programme in 2016, the ESRG report found that renewables were about 60% cheaper than new coal plants on an LCOE (levelised cost of energy).

Project developers were paid R0.62 per kilowatt-hour for solar and wind and R1.03 per kilowatt-hour for coal.

As the latest REIPPPP Bid Window 5 results show, the price for renewables has dropped even lower (while the cost of new coal build has not reduced).

Ayesha Jacobs, a junior mechanical engineer who works in the renewable sector of Zutari, said: “Renewables are cheaper per kilowatt-hour than coal. With renewables you don’t need a fuel… you just keep using the natural resource, but with a coal plant you have to keep buying the fuel.”

Professor Nicholas King, environmental futurist, global change analyst and strategist, agreed, saying “you don’t have to mine, transport and burn fuel — like you do with coal. The same for oil, same for gas. And the massive infrastructure that goes along with all of that — none of that applies with renewable energy sources. Once you have the infrastructure in place, basically, the energy comes to you and you just convert it, whether it’s wind or solar.”

King said another reason is that it’s a new technology. “With coal and oil, or gas, fossil fuels… most of the low-hanging fruits have long been mined out and utilised and burnt. So it just gets more and more expensive to utilise fossil fuels.”

Plus, with all massive infrastructure, our coal and nuclear power stations have an end of life, said King.

He said: “This idea that we must just hold on to this thing and not change is crazy. I mean, technology has changed human development for centuries. And nowhere is there an example of a technology which is replaced by better technology continuing to exist.”

Inglesi-Lotz said we shouldn’t be asking which form of energy is cheapest. “In my view, what we should be asking is what is the energy source that will give us multiple benefits including low cost but also reliability and sustainability.

“The answer to what is the cheapest is an easy one if somebody looks at the data and the technology. But, is the cheapest energy source today going to be the cheapest energy source tomorrow? Energy investment and planning depends highly on how good we are in predicting things and the recent events of the pandemic, for example, has taught us that models can be faulty.”

Is renewable energy unreliable and intermittent?

A common argument against renewable energy is that it provides an intermittent source 0f energy — not consistent or steady — because the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow.

Physics professor at the University of Johannesburg, Hartmut Winkler, whose research interests include solar irradiance, solar energy and active galactic nuclei, said: “The most critical problem with entirely replacing coal with renewable energy is, however, caused by the intermittency of renewables. On still, overcast days renewables cannot produce any electricity.

“While South Africa has very favourable weather conditions, and proportionally about double the sunshine and wind of a typical European country, and a large enough geographic spread that makes it statistically almost impossible for there not to be wind or sun somewhere in the country on any day, there will be large chunks of time when 120GW of renewable power installed will not meet power demand (early evening is particularly vulnerable).”

Engineer Jacobs agreed, explaining “because renewables are intermittent, we will need a baseload for when there is no wind or sun. Batteries help with the intermittency but also have a limited capacity, so if both have run out you will need a base or backup load.”

Winkler said that to circumvent this issue requires storage in the form of massive batteries, and at this point we are not at the stage where these technical storage requirements can be met, in part because huge storage capacity is expensive.

“There have been very promising moves in the last few years, but we are not yet at the point where coal can be replaced by renewables in a practical manner,” says Winkler.

Jacobs said that “because battery technology has developed rapidly in the last few years and we now have the option for mass storage solutions, it is likely to develop further to allow us to store even more energy at lower costs. But yes, it will take a while before this happens.”

Inglesi-Lotz agreed: “I must say technology develops rapidly.

“Renewable energies could not compete cost-wise with fossil fuels 10-15 years ago but now as technologies get developed and they get commercialised, we are at the point that we have this discussion of whether solar and coal are comparable.”

Inglesi-Lotz added, “For a more controversial response to the intermittency argument, especially for South Africa, the unreliability of coal-generated electricity, as well as the uncertainty with regards to the coal markets nationally and internationally, have created ‘intermittencies’ in the form of load shedding.”

Dlamini said that “it is a fact that renewable energy is intermittent. It is not a fact that renewable energy is not a good source of alternative energy.”

Are gas and nuclear worth the hype?

Many people promote the use of gas or nuclear as an alternative form of energy or as a “backup” energy supply for when renewables face intermittency issues.

Gas

Jacobs said: “With gas, there’s an immediate effect on the environment when producing, which is large carbon emissions (which nuclear doesn’t have), but there is no waste.

“The reason why gas is preferred is because it has the shortest start-up time out of all the alternative power sources, so that when the renewables do drop, you can pick up the power quickly with gas as the baseload.”

Yelland explained that gas is seen as a transitionary technology — as an interim measure while these other technologies (like battery storage) mature.

Yelland says the appeal is that gas is a mature technology (gas supply all around the world) and gas infrastructure is quick and cheap to build.

However, he points out that gas prices have become very expensive in the past years and are more expensive than when the IRP ran that model.

“If you were to do it today (model), at the latest prices of LNG (liquified natural gas), you’d get a different answer,” said Yelland.

Nuclear

Jacobs said “it is hard to compare. With nuclear you have long-term toxic waste which is obviously very bad because of the radiation, things can go wrong (although very unlikely these days) and the mining of the materials has large carbon emissions.”

Kruger said that a problem with nuclear, like coal, is that it is not an energy source that can be switched on and off quickly (unlike gas, batteries, or pumped storage).

“To meet this variability in the system you need something that can respond in seconds,” explained Kruger. “So coal for example takes hours. Nuclear takes days.

“So nuclear, once you switch it on, it has to stay on, basically. It’s not something you can switch on and off quickly, or ramp up and down.”

Yelland agrees. “You can’t meet the gaps in renewable energy from nuclear power. You cannot respond quickly enough.”

Kruger adds that to build new nuclear would definitely be more expensive than just building solar, wind and something flexible.

Winkler said: “I find it astounding that there are still people promoting a nuclear solution to South Africa’s energy woes. The sector is badly tainted following the Zuma nuclear deal with Putin, and I have yet to hear nuclear advocates distancing themselves from what happened.

“Even without that sorry history, the big problem with nuclear is that it takes so long to build a plant.”

How much renewable energy would we need to power the country?

Winkler said: “Something important to consider here is the distinction between power and energy.

“A wind farm of 100 megawatts (MW) sounds like it is equivalent to a 100MW coal plant (note: Medupi is 4,800MW), but it is only achieving this when the sun is shining overhead, alternatively when the wind is blowing.”

Winkler explained that due to the intermittency of renewables, wind and solar farms are not operating at full capacity.

Kruger agreed there is a difference between capacity and energy, explaining that if the wind was blowing strongly a wind farm would generate its full capacity, but because that’s not the case and because you measure energy over time (how many megawatts per hour it’s producing), it will always be less.

“Wind farms generally, for example, operate at like 30-40% of their rated capacity. So over time, a wind farm of 100MW will probably have 30-40MW-hours, whereas a coal plant of 100MW operates at a higher capacity factor — it’s normally supposed to be around 80%.”

Winkler said: “In reality, the amount of energy (as opposed to power) needed to offset a 100MW coal plant (one that is running properly, not the forever breaking down Eskom plants) would require a solar or wind farm of about 300MW.”

So, if we were to completely replace the current coal power capacity — which is about 40 gigawatts — we would need about 120GW of wind and solar.

Winkler stressed that this does not mean that renewable plants are three times more expensive.

He explained that you pay “per apple” (per kilowatt-hour, which is the electricity produced by a device generating 1KW running for one hour ) — it is just that the renewable farms only serve “apples’ for about eight hours per day.

“Just because apples are only available for eight hours per day, it does NOT mean that when you buy one it costs you three times as much as it would when you can buy them 24/7.

“So building 120GW of renewable plants is definitely much cheaper than building 40GW of nuclear or coal plants.”

Kruger agreed, saying that based on the IRP model, building and operating renewables even with backups is still cheaper than new coal or new nuclear.

Why don’t we have more renewables?

If the model the IRP and other bodies use is saying the least-cost scenario (and one that meets socioeconomic and climate objectives) is mostly wind and solar (with a bit of batteries and gas)… why do we have so few plans for renewable energy?

As it stands, we only have 6GW operational — which is just 5% of 120GW of renewable energy to power the country. Even with the 2.5GW of new renewable energy contracted from REIPPP bid window 5, we should have a lot more.

The 2019 IRP only includes plans for 33% of renewables by 2030.

“Now that is a good question and reflects politics and the competing interest groups operating in the energy space,” said Winkler.

Winkler said we could “most certainly” have more renewables than we have now, citing other countries that have done so. Germany is approaching 50% and Costa Rica has 100%.

“I see no reason why South Africa could not achieve 50% of electricity (with at least the same degree of reliability as at present) from renewables by 2030, if that is what it really wants.

“A much more aggressive renewables development strategy is definitely possible. If a new IRP were to be prepared today (without taking account of political and energy interest group considerations), it would definitely result in a much larger renewable energy allocation than we have in the 2019 document — 50% is very much feasible, especially if decarbonisation incentives make renewables even cheaper than they have already become.

“One of the biggest failings of the DMRE is that they have not produced a revised IRP 2021. The IRP is supposed to be updated every two years! Maybe some people do not want it to be updated?”

Where do we go from here?

Kruger said that the last thing South Africa should do with the funding from the R131-billion deal is put it all into building renewable infrastructure.

Kruger explained that “what we’ve seen is that there’s more than enough money around. Everyone’s willing to invest in renewables.

“What that money should go into is helping Eskom and the government deal with the issue of shutting down coal plants sooner. Mitigating the impact of that on communities around those coal plants and workers — retraining them, getting them into new sectors.

“And two we’re probably going to need more transmission infrastructure, so building that. And three, the biggest thing — refinancing Eskom’s debt.”

Yelland had similar feelings: “My view is that we must stop building non-renewable energy sources. We must allow non-renewable energy like coal to reach end-of-life and be decommissioned.”

Inglesi-Lotz said: “The more I research on the energy sector, particularly in South Africa, the problem has nothing to do with available natural resources or access to technology.

“The problem has a lot to do with leadership, management and the quality of institutions or as defined in the literature, the rules of the game.

“I think what the energy sector needs is evidence-based policy-making without biased and lobbying interferences.” DM/OBP

Additional reporting by Ethan van Diemen

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8821″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Nice explainer. Note that UCT-ESRG does not use Plexos as its software, and believes that with its custom-built SATIMGE platform, it can predict future electricity needs more precisely than with the techniques used in the IRP2019 – which the IRP text explicitly acknowledges as deficient.

Households should go solar. Taking a lot of people of the grid.

A big issue in this debate is how much we trust the debaters. The public trust in govt has been eroded completely by the ANC and yet it and they and theirs have to be trusted to do the right thing and do it fast. We have several decades of them doing the wrong thing very consistently and doing wrong well. Time is not on the public’s side and we have the choice of the devil we know and not much else. Or is there another way?

A million MicroGrids will still save our little nation. Want to know more about MicroGrids ? Read up on what the IEEE, CIGRE, and EPRI are talking about – it’s a big deal, and it’s the future

After Germany’s massive push into renewables in the early 2000s, it later had to ramp up coal stations to meet demand and now has some of the most expensive electricity in Europe, with a “renewables subsidy” of 25% built into the price that consumers pay. France has of the cheapest electricity prices in Europe and most of their source is nuclear. Nuclear represents the best long term solution for base load supply and the fear around it is simply unwarranted. Obviously the public’s fear around whatever the ANC touches in this whole policy process is wholly warranted.

Saving energy is far cheaper than generating energy. In this respect water heating accounts typically for between 35% and 55% of the monthly domestic electricity bill. Solar water heaters can remove most of that energy and in particular can avoid the MW peak draw in the evenings (overcoming a major issue). Solar water heating is the lowest hanging fruit of all the (renewable energy) options but is basically totally ignored. If South Africa ever adopted incentives or tax rebates to consumers in both domestic and business for solar electric generation and also allowed consumers to feed back into the grid, the countries power problems would rapidly become a thing of the past. Australia is a good example of power deficit to power surplus in just 10 years as a result of solar PV consumer investment. Regrettably the government casts aside any behind the meter renewables opportunities and constantly drags its feet on implementing more and larger renewable projects as part of the overall energy mix.

Look to the market!

Ignoring green goals, renewables have overtaken coal and nuclear and gas. I seriously doubt any of those studies imagined the 35-45 c/kWh wind and solar bids just awarded. That means renewables cost, after a profit in IPP, half the MARGINAL coal energy cost.

If cheap finance and profits are taken out, Eskom could own its own renewables for 25c/kWh.

Also, a large chunk of the lower Eskom sales is due to private power. How many GW of solar is sitting on factory roofs??

Intermittency: there was already a study showing how much wind and solar would fully cover our needs. If we could build around 10GW backed by 50GWh of hydro storage then the at times surplus wind and solar would see us through.

We need to park green politics. a bunch of people that don’t like the other politics of the greenies are automatically anti-renewables.

Imagine the economic and jobs impact of reliable power that is also fixed in escalation forever.

Presently, renewables are the cheapest source of electrical energy for the country. Private sector can, and are very willing to supply the electricity at cost effective rates as is shown by the over-supply of bids in the recent bidding window. Where ESKOM needs to invest is in:

1. creating the transmission network to areas with the greatest potential for

– renewable energy production such as the northern Cape and

– large energy storage including water pump storage.

2. creating enabling rules and infrastructure for small suppliers including homes, mines and factories to put power back into the grid at renumeration rates that are higher when the needs of the system are at their greatest. They could then release energy (stored in their batteries from windy or sunlight hours) during early evenings, for example, when the need is highest, at a higher renumeration rate per kW.

We do not have the luxury of a 30-year nuclear build. Let’s bin this idea once and for all.

My take-away from this: “Maybe some people do not want it [the IRP 2019] to be updated?” Precisely. We are far behind where we should be i.t.o our renewable generating potential in SA because government is and has been captured by a nuclear/coal lobby, and I’m including the relevant minister in that assessment. The hot mess of blackouts since 2008 is evidence of that.

How is it that City of Joburg could buy 87,000 and only install 7,000 of them while spending R300-million on storing the rest? Unbelievable!

Let’s repeat:

87,000 geysers bought;

7,000 installed; and

R300-million spent on storage

Criminal!