South Africa

Op-Ed: Michael Dingake on legendary communist leader Moses Kotane

Moses Kotane was a famous South African Communist Party (SACP) leader who was general-secretary for some decades as well as a leading figure in the African National Congress (ANC). Paradoxically, despite being a communist he was the main confidante and most trusted adviser of both Chief Albert Luthuli and Oliver Tambo, both of whom were fervent Christians. Kotane was known as a strict disciplinarian as well as a careful and thorough thinker. He never entered a conventional schoolroom but was mainly self-taught or learned in communist night schools. He was recognised as a leading theorist, who contributed greatly to the development of the strategies of both the ANC and SACP. This is MICHAEL DINGAKE’s account - from his book Better To Die On One’s Feet - of Kotane’s personality and how the young Dingake engaged him on religion, the use of violence and other matters.

(This is an extract from Michael Dingake’s book Better To Die On One’s Feet, published this week by South African History Online.)

Moses Kotane impressed me as a different type of leader. Outwardly aloof, abrupt, authoritarian and haughty, Malome (uncle, as he was commonly known) imparted the understanding of socialism to me as no textbook on Marxism could ever do … We interacted through informal chats and later, formally in party meetings, mainly in district conferences and at one party national conference which adopted the peculiar SACP policy document The Road to South African Freedom in 1962.

Kotane’s stern manner, which intimidated many who were unaccustomed to his personality, did not deter me from plying him with questions and provoking him with my radical opinions whenever I had a chance. In the end, I found that beneath the facade of austerity and aloofness lay a treasure of wisdom; a layer of charm, amiability and amazing intellectual capacity which I exploited to the best of my abilities.

When I began to express doubts about religion, because I was disillusioned with what I considered to be the hypocrisy of the men of the cloth and their ‘word’, Malome was brusque: “Why must you doubt them? And why must you think they must think you unhypocritical when you express your ‘religion’, or whatever it is, to them? You must engage them in serious discussion, talk to them and hear their side of the story, and why they say what they say and do what appears to you to be different from what they say!” He would then tell me about some of his peers in his youth. When they asked him to attend church services with them on Sundays, he agreed, on condition that they went to political rallies with him after the church services. This way they gained his trust and he managed to draw them into politics. None, afterwards, could sell them the story that communists were ‘anti-people’ or ‘anti-church’.

I was in the habit of challenging the ANC policy of non-violence, when the government lived by the sword. I ridiculed the idea of winning a war with words against a deaf-mute enemy wielding a sword. He dismissed the hyperbole, and said it was typical of youth trying to defend their lazy style of work. He interrogated me about the number of youths who were prepared to sacrifice their lives for the nation. He suggested that those who were ready to sacrifice their lives wanted to do so for themselves, not for other people, by means of armed robberies and gang-warfare so as to gain a personal ‘tough-guy’ image. These ‘toughies’ were unprepared to serve their community in a capacity as soldiers in the peoples’ army.

Malome argued that non-violence was not a matter of principle for the liberation movement, but a convenient strategy for the moment. In the meantime, the youth must prove themselves by mobilising the masses to support intense non-violent campaigns before they can embrace radical forms of struggle. Stop trying to jump the gun!

Malome was not a freedom-square rabble-rouser. He was rather a pedantic speaker, paying attention to facts and language construction. He was at his best in committee meetings, at drafting political statements and arguing refinements of policy. He was a major influence in policy formulations and was particularly responsible for bringing the ANC and the Communist Party (CP) into closer working relationships. He did much to harmonise not only the policy and strategies of the Congress Movement and the party, but also interpersonal relations within the movement by insisting, for instance, that party members desist from trying to impose CP decisions on the ANC, South African Indian Congress and the South African Coloured People’s Organisation, if they were participating in these at that level. In other words, members who held dual membership of the CP and another member (organisation) of the Congress Movement had to contribute to these organisations as members of that particular organisation, not as members of the CP, dictated to by its partisan decisions or influence.

A number of tributes to the role of Kotane in the struggle follow:

During the year that they were in the case (treason trial) together, a remarkable understanding developed between Chief Albert Luthuli and Kotane. In their persons can be discerned the relationship which came to exist between the illegal Communist Party and the ANC.

Nothing was done by the CP which was in conflict with Congress policy. On the contrary, CP members were seen to be the most active in carrying out Congress decisions and working in campaigns, and this established a unique unity and mutual confidence between the two organisations. It was this unity which underlay the enormous popular upsurge by the masses in South Africa during the decade of the 50s … Tambo has stated: “I think Moses Kotane contributed more than anyone to this kind of collaboration between the ANC and the party, to the unification of the liberation movement in South Africa … I am absolutely certain that many people who might have been hostile to the party were won over because they found a man like Kotane to be an ANC man second to none.

“It is significant that Chief Luthuli, who was not a member of the CP, and not near to being a member, by-passed his officials and secretaries on difficult questions on which he wanted advice and sent for Kotane, because he had discerned this loyalty in him. He knew Kotane was a 100% member of the CP – its general-secretary, in fact – but he also knew him to be 100% ANC, and this gave Luthuli confidence in him.” (Brian Bunting: Moses Kotane op. cit, p229-230)

While Tambo said truthfully that Luthuli was not a member of the CP, his assertion that he was “not near to being a member” was somewhat presumptuous, considering the views cited about their mutual regard and estimation:

Over the years that they worked together, the two men developed a high regard for one another. Kotane found Luthuli broad-minded and tolerant … “I am sure he would have joined the CP if I had asked him,” said Kotane later. “Not because of the name or the philosophy, but because of our programme and the work we were doing in South Africa, and because he and I were so close together.” Luthuli, in fact, once confessed to Walter Sisulu: ‘I am not a communist, but if Kotane ever asked me to join the party, I wonder what I would do.’ (Moses Kotane op. cit., p.233)

The transformation in the relations between the ANC and the CP, brought about largely by the influence of Kotane, was dramatic, considering the background of these relations in the ’40s and the early ’50s. Although the CP had always striven for warmer relations with the ANC by recognising the legitimacy of black aspirations, the ANC, represented by both the conservative elements among traditional leaders and the radical elements in the ANC Youth League, had remained suspicious, as can be gleaned from these:

When the Suppression of Communism Act was passed in 1950, it had tacit support in surprising quarters – not least the ANC, just then undergoing its own transformation from an acquiescent reformism towards a greater militancy.

This development was largely owing to the activities and energies of the ANC Youth League (ANCYL), established in 1944 under the leadership of Anton Lembede and a core group that included Mandela, Sisulu and Tambo …

By 1949, the youth league’s insistence had helped to produce the ANC’s Programme of Action, in which for the first time the organisation declared itself prepared to use extra-parliamentary and extra-legal forms of mobilisation, including boycotts, strikes, civil disobedience, non-cooperation and national stoppage of work. At the same time the ANCYL followed a resolutely African nationalist line, which made it wholly hostile towards communism.

And so, as Nelson Mandela put it later, “we were not unsympathetic to the banning of the CP”. This was despite the fact that many realised (as did Mandela) that among the targets of the Suppression of Communism Act was the ANC itself. Moreover, when the CP dissolved, the youth league doubled its disdain, because to them the weak-kneed surrender merely proved the bad faith of the communists and their capacity for betrayal of the cause they claimed to support.

When stay-aways from work were called on May Day 1950 in solidarity with Kotane, JB Marks and Yusuf Dadoo – all members of the CP – as well as others who had been restricted under the Riotous Assemblies Act, the ANC was involved in all kinds of mixed response, which only underlined the ambiguities and rifts. (Stephen Klingman: Bram Fischer the Afrikaner Revolutionary, pp188 – 189)

In the absence of men like Kotane, who knows what road the South African liberation struggle could have taken? Kotane, of course, was not alone. His colleagues, Govan Mbeki, Mike Harmel, Sisulu, Bram Fischer, Dadoo, and many others believed in the Marxist theory, and diligently analysed its precepts and how best they could be applied in the complex peculiarities of the South African situation. Each one of them contributed his or her unique character to the unfolding political scenario. Yet Kotane was primus inter pares (first among equals).

They all had in common their love for their country and its people; the ideology most appropriate to setting it free, affording all its peoples the opportunity to live in harmony and prosperity. They debated long and hard about the strategies to be devised and the most effective weapons to be used. At the fifth national conference of the SACP, to which I was a delegate, and for which the programme was entitled ‘The Road To South African Freedom’, the following, inter alia, was stated:

In this programme, the SACP states its fundamental principles. It surveys the vast changes which are transforming the world and the continent we live in. It analyses the historical roots and the underlying realities of South African society. It puts forward its answers to the problems facing the people of our country today. As its immediate and foremost task, the SACP works for a united front of national liberation. It strives to unite all sections and classes of oppressed and democratic people for a national democratic revolution to destroy white domination. The main content of this revolution will be the national liberation of the African people … The CP has no interests separate from those of the working people. The communists are sons and daughters of the people, and share with them the overriding necessity to put an end to the suffering and humiliation of apartheid. (Lerumo, A., Fifty Fighting Years, p140)

For those who thought communists believed in nothing but abstract communism and an unattainable communist society, this programme must have been a telling blow. Yes, communists target the highest peak that human talent and aspiration wish to scale. But communists are men and women born and bred in the realities of everyday life. They are intelligent and honest people who know that to reach the mountain peak, you have to do it in stages, training every climber, mostly convincing them of the importance of moving up as one organised group of mountaineers, taking particular care not to antagonise any potential fellow-traveller. Pragmatism is the key to success. The South African situation, with its rugged features of contrasts and unique challenges, required, and still calls for, lucid minds and political skills to unravel the web of intricate relations so as to chart a consistently progressive and pragmatic path. DM

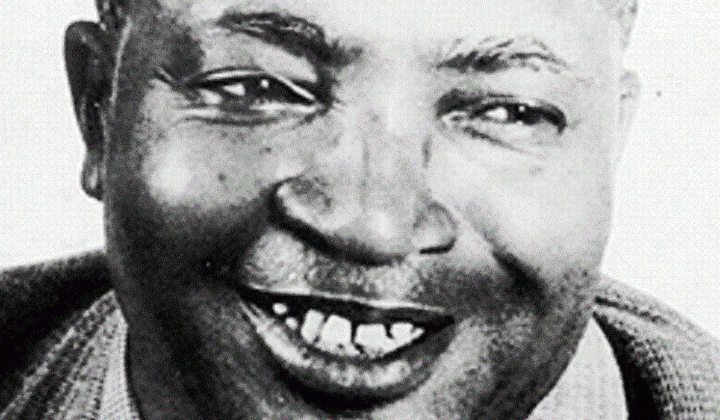

Photo: Moses Kotane

Become an Insider

Become an Insider