Maverick Life

One woman’s extraordinary journey: ‘Je suis Eugene de Kock’

In January this year Eugene de Kock, one of Apartheid’s most notorious state assassins, became a free man. Three years before his release, an Afrikaans-speaking mother of three, Anemari Jansen, needing to escape the ennui of suburbia, and also in an endeavour to come to terms with what it means to be an Afrikaner in post-Apartheid South Africa, began visiting De Kock in prison. Her recently published account of their relationship is a compelling, disturbing, brave and timeous voyage of discovery and recovery. By MARIANNE THAMM.

In December 2012, a year after Anemari Jansen had first begun her regular visits to De Kock at the Kgosi Mampuru II prison (formerly Pretoria Central), the country’s most notorious assassin wrote her a letter, setting out some of the things he would like to do if or when he was ever set free (he was finally given parole on 30 January 2015).

De Kock told Jansen that he wanted to live his life “with simplicity and silence and as much dignity as possible.” He added that he would like to find gainful employment to sustain himself, that he would perhaps approach the media for a job that “others wouldn’t want to do”.

“The more dangerous the better, like second-by-second reporting in the vehicle right up front in the frontlines like in Libya,” De Kock wrote.

His clothes, he added, would be “ordinary, practical, neat, workmanlike/outdoorsy, a pair of Hi-Tecs…Nothing expensive, just good quality that will last and last, but as little as possible”.

He was also keen, he said, to set up a bird feeder somewhere as well as watch to his favourite film, The Scent of a Woman, with Al Pacino “six or ten times” because “the depth of it and the never-give-up factor is palpable”.

De Kock told Jansen he would like to see his sons, who live overseas with his former wife, and whom he has not seen for 20 years. And then the strange disjuncture of De Kock’s stated desire to “take care of my health” by making an appointment with Dr Wouter Basson, notorious cardiologist and former head of Project Coast, the Apartheid state’s secret chemical and biological warfare project.

“I have arrangements with Dr Wouter Basson for all the medical tests that have to be done. I will also seek his advice in relation to other aspects, because while I might be older [De Kock turned 66 the day before he was granted parole] I don’t plan on going to my grave celibate. I don’t believe in that. Definitely not! My role model is the late Dr Chris Barnard.”

Somehow an appointment between “Prime Evil” and “Dr Death” for a mundane and routine medical checkup is beyond imagining. Were it not for the horror of the countless brutal and gruesome deaths directly or indirectly linked to the actions of these two men, it might serve as a scene from a very dark and disturbing graphic novel.

Basson refused to seek amnesty from the TRC for his role in Project Coast. And while the TRC found that he had been the primary decision-maker responsible for the “elimination” of SWAPO prisoners of war and SADF members who apparently posed a threat to South Africa’s covert operations and that he should be criminally charged, Basson was later acquitted and granted amnesty after a after a 30-month trial that began in 1991.

While it is understandable that a political mass murderer like Eugene de Kock – who served as a scapegoat for Apartheid’s crimes against humanity and who was rewarded repeatedly for his grisly, illegal work by his superiors who remain unpunished – would be of interest to academics and scholars like Professor Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, author of A Human Being Died That Night, it is curious that an ordinary mother of three would seek a close and intimate audience with the killer.

While it is not uncommon for women to be romantically drawn to incarcerated killers, Jansen’s decision to make contact with De Kock was triggered more by a deep and unsettling notion that as an Afrikaner who had been raised in Apartheid South Africa, she needed to return to the “source”, or perhaps the most grotesque manifestation of the ideology in order not only to come to terms with her history but ultimately with herself.

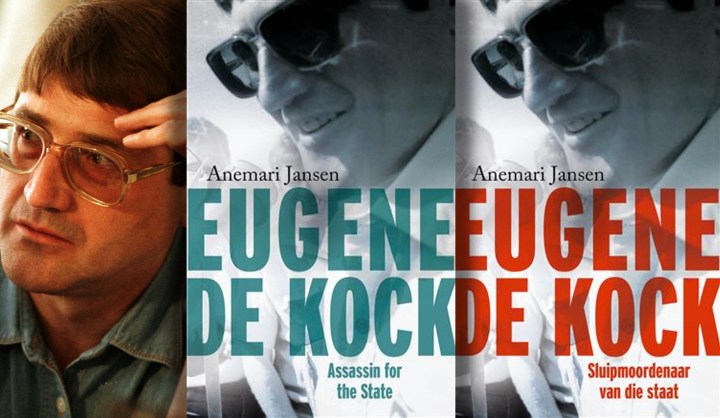

In that sense her book, Eugene de Kock – Sluipmoordenaar van die Staat, soon to be released in English as Eugene de Kock – Assassin For the State (Tafelberg), is a strangely compelling and painfully honest attempt at owning and confronting the howling ghosts of the past.

Jansen writes, “To tell the truth, I hadn’t thought about Eugene de Kock for years. Like most other people seated around dinner tables. To me he was the man with the glasses who (sic) we used to see on TV. I do, however, remember that shortly before his court case in 1995 he was one of the most highly decorated policemen in the old South African police.”

She sketches growing up as an Afrikaner in Alberton in Apartheid South Africa, the obligatory celebration of The Day of the Vow (as Reconciliation Day was known then), of going to the NG Church, of carefree parties, of servants who lived in cramped “servants’ quarters” and who called her “nonna” and her brothers “klein baas”.

For Jansen life is easy and oblivious. After finishing school she marries a civil engineer and quickly has three children while moving between Namibia and South Africa. And then one day she begins to feel unfulfilled, dulled by the ennui of suburbia and the routine demands of motherhood. During a discussion about De Kock at dinner one evening, she writes, she reached a “turning point” and undertook to “challenge” herself. Afterwards she arranged to meet De Kock through University of Johannesburg academic, Piet Croucamp, who had befriended him.

After her first and manic encounter with De Kock in 2011 she writes, “Something shifted in my consciousness.”

“Was I asleep during the 1980s and early 1990s? I was born in 1964 and grew up during the height of Apartheid. But when I think back on my youth, I am shocked at how uninformed and naïve I had been. Did I not want to know how the country was burning or was I just blind?”

And then, “Thirty years later I want to shrink with shame because of my ignorance, how apathetic I had been and by my acceptance of the illusion of normalcy during a time when a low-intensity civil war raged in the townships and South Africa was involved in a full-scale war in the then South-West Africa.”

And so began Jansen’s peculiar three-year relationship with De Kock. Her book is not an attempt at humanising or romanticising De Kock or sanitising the extent of his criminality in any way. Jansen allows De Kock to speak and express himself using the language that he knows, including terms like “terrorist”. It is as if De Kock found it easier to speak freely to an ordinary Afrikaner woman and the portrait that emerges is one of a complex and repressed man who has genuinely come to terms with the extent of the harm and pain he has caused.

De Kock’s gradual excavation of his contaminated psyche is fascinating, tender and repulsive. There are flashes of anger when, at the conclusion, De Kock suggests that prominent Afrikaans novelist, F A Venter, who authored several titles including Geknelde Land (A Country Afflicted) and Die Keer toe ek my Naam Vergeet Het (When I Forgot my Name) should have penned a book titled Vervloekte Fokken Land (Cursed Fucking Country).

“I will never pick up a weapon for any country. Never,” writes De Kock.

Jansen’s is a sincere and brave attempt at understanding the man and how he came to be. How she came to be.

Eugene de Kock did not emerge into the world fully formed. He was shaped, moulded and manipulated by a toxic brew of racial nationalism, religion, patriarchy and a grand and fictitious historical narrative that held a nation – including Anemari Jansen – in its thrall. It was an ideology that cost the lives of thousands of South Africans, almost all of them black, who opposed the brutal system.

“I think differently about many things after tracking Eugene’s life for three years. Nothing will ever be the same. Not for Eugene de Kock or for me,” she says.

Jansen writes that it is important to reopen the wounds of the past and to listen to the ordinary men, the conscripts, the foot soliders of Apartheid, who were also damaged by the system and who today live with the scars.

She quotes author Antjie Krog’s observation in Country of My Skull: “And suddenly I know; I have more in common with the Vlakplaas five than with this man (F W De Klerk). Because they have walked a road, and through them some of us have walked a road. And hundreds of Afrikaners are walking this road – on their own with their fears and shame and guilt. And some say it, most just live it. We are so utterly sorry. We are deeply ashamed and gripped with remorse”.

Many who may not feel the inclination or need to revisit the past will no doubt meet Jansen’s book with howls of anger, denial and derision. The project of healing, as post-war Germans learned, is an ongoing one, in spite of contemporary political developments. It is the work of the soul. A general hardening of attitudes in the country is perhaps, as a result of our inability to engage with our past in the manner Jansen, an ordinary woman, has done.

One of the most valuable insights gained, writes Jansen, is that in confronting her past sincerely and honestly: “I can learn, as an Afrikaner woman, how to tackle the future without guilt but with the necessary responsibility, insight and respect.”

During one of her last visits to De Kock on 24 January this year (coincidentally his eldest son’s birthday) Jansen asked him if he understood that had he been found guilty of the same crimes by the government he had loyally served he would have received the death sentence. De Kock’s reply belies just how much the notion of being a “soldier” still informs his “peculiar integrity” as his friend, Piet Croucamp, termed it.

“Yes, I would have…And I would not have opposed it. I would, however, have liked to determine the method. It would have to have been by firing squad, one that would have to be handled by my friends and family, especially those from the army and the SAP. They would do it. I would not like to be executed by ‘the enemy’.”

Jansen’s unusual book is an important contribution to the ongoing and necessary debate about what it means to be a South African, how to own and make peace with the past, and how to find a way of believing in a future. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider