South Africa

Nelson Mandela – many legacies, one man

Twenty-seven May this year marked the 50th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s first arrival onto Robben Island (he actually was received there twice, the second time after the Rivonia Trial was decided). Once incarcerated there, he eventually became the country’s most famous political prisoner (and most likely the world’s best-known one as well), as he spent much of the next three decades of his life before he finally left Victor Verster Prison on 11 February 1990 for a then still-uncertain life of political activity and personal freedom. Now, the nature of the legacy of this nonagenarian, elder statesman, a man who has not made a significant public appearance since the 2010 World Cup, is coming forward anew, even as his children squabble over money with the custodians of his finances. J BROOKS SPECTOR examines the crucial role of the newly refurbished Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory in the Mandela legacy effort.

In the heart of Johannesburg’s old central business district, the Rand Club – housed in a massive British Empire-era, Beaux-Arts building – was where deals decided the economic fates and wealth of nations with a handshake while the negotiators enjoyed a proper men’s club-style lunch. Up until today, the walls and display cabinets in the club still offer maps from colonial Africa, 19th-century prints of lion hunting and paintings of glorious military victories, antique muskets and cavalry swords, as well as the inevitable models of Spitfires and Hurricanes.

The Rand Club was where the mining houses’ defence committee met during the 1922 miner’s strike when the white workers in the gold mines (supported by South Africa’s Communist Party, no less) fought pitched battles against South African army troops in an effort to keep any of their jobs from being opened up to black South Africans who would have worked for lower wages. For a century, the portrait on the wall at the top of the Rand Club’s imposing central stairway was that of the reigning British monarch – most recently Elizabeth II.

Even if the ghosts of mining magnates like Cecil Rhodes still haunt the building’s darker corners, many of the club’s newer members look more and more like the country’s demographics – in a dramatic change from earlier generations. However, it was only a few years ago when Elizabeth II’s portrait was relocated to a side alcove, now replaced in the central spot by a larger-than-life picture of Nelson Mandela, in a suitably presidential posture. Like the rest of South Africa, even the Rand Club has grappled with how best to embrace the extraordinary legacy of Nelson Mandela.

On that anniversary date of Monday, 27 May, the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory (NMCM) invited guests to celebrate the centre’s re-opening – following a major renovation and refit. And as part of the event, Achmat Dangor, the NGO activist, author and man who had shepherded this rebuilding, handed over his CEO-ship to Sello Hatang, as the man who will manage the centre’s way forward as conserving and shaping the legacy of Nelson Mandela becomes the centre’s crucial institutional task.

Separately, this event coincided with the long-awaited formal announcement of the impending release of the biopic based on Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, scheduled for 29 November 2013. Without doubt, the pushing and shoving that will break out in order to score invitations to the opening night premiere of this film will almost certainly be well beyond any previous opening night in South African history.

This film features a host of well-known local actors and actresses, but British actor Idris Elba stars in the role of the adult Mandela. The film has been in the works for a long time; planned by local film magnate Anant Singh, ever since he first secured the rights to turn the Mandela autobiography into a film back in 1996. According to the producer’s company, when the real Mandela saw stills from the film, he is reported to have said, “Is that me?” – presumably an expression of wonder at the eerie closeness of Elba’s portrayal of him as a youngish adult.

Already informally dubbed by some as the “not your mother’s Nelson Mandela”, with its gutsy portrayal of an intensively physical, athletic, political figure rather than the near-saintly version in works like the recent film, Invictus; Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom is poised to be the latest – but certainly not the last – effort to define the nature, importance and impact of one of the 20th century’s seminal political actors.

There are undoubtedly thousands of book titles about him in print already, in dozens of languages. (Books about Abraham Lincoln, Napoleon, Shakespeare, Queen Victoria and Christ presumably still outnumber those about Mandela – although the lives of these other figures have already been written about for a lot longer period of time). There are Mandela comics and voice recordings on CD, operas about him, and still other films, documentaries and made-for-television miniseries already in circulation that focus on his life, loves and political activities. Portraits and photographs of Nelson Mandela continue to decorate homes throughout the country, and any exhibition of photographs about him is certain to draw huge, adoring crowds. Moreover, a photo taken with Mandela remains one of the most prized pictures for the brag wall of any politician – anywhere in the world.

But pinning down his precise legacy for the future is already a major preoccupation for historians, politicians and social activists. While the well-known Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund is an important charitable NGO operated in his name, the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory (NMCM) is probably the crucial part of the Mandela legacy effort (although his traditional home in the Eastern Cape and the spot in KwaZulu-Natal where he was arrested by the South African Police will eventually become major historical places of veneration for certain). The NMCM, housed in its newly refurbished headquarters in the upmarket Johannesburg suburb of Houghton, near Mandela’s own private residence, is patterned after and functions similarly in many ways to those American presidential libraries that house respective presidents’ official papers and related items.

Documents, memorabilia and digitalised audiovisual materials covering the life and work of Nelson Mandela and his time have been collected and carefully archived. His post-presidential office has been preserved as well. The prestigious Nelson Mandela Lecture – featuring the likes of world figures like former US President Bill Clinton – is hosted annually. Unsurprisingly, it remains a hot ticket for South Africans interested in public affairs – and in being in proximity to the aura of the former South African president. An online archive – made possible by the support of some major international software/IT companies – is available for scholars and other interested individuals worldwide who wish to access a wide array of period audiovisual materials and official and personal records. And, of course, the centre also carries out the usual run of conferences, colloquies, seminars, workshops and publications – all dedicated to examining the circumstances of Mandela’s life, work and influence on the world stage, and how that Madiba (his clan honorific name) magic can be applied to other world sore spots.

But clarifying the Mandela legacy is not quite as simple as noting that he was the country’s first black president, the first president selected in the country’s first universal franchise election, and the man who helped heal a nation on the verge of civil war – or wars. He was not a George Washington who won his nation’s freedom on the battlefield and then became its first elected leader, nor an Abraham Lincoln who led a nation in the midst of a terrible civil war. He was not a Winston Churchill who mobilised, energised and then led a nation in furious battle to help defeat Nazi Germany and thereby save Western civilisation. He was not an Asoka who unified a subcontinent into a great empire, nor a Vladimir Lenin certainly, nor even a Mahatma Gandhi who led India towards independence, using a pacifist ideology created specifically to avoid the shedding of blood.

Instead, perhaps, the model might be something like Cincinnatus of ancient Rome, who, called back into active service, defeated his city’s foes and who then chose to retire quietly to his farm, rather than rule for life as his countrymen surely had hoped. Although time has yet to answer this question fully, perhaps, too, he and Burma’s Aung San Suu Kyi are cut from something of the same cloth. Indeed, he came out of prison when most men would be ready to retire, and then worked strenuously to convince the greater portion of his fellow countrymen and women that the country really did belong, in the words of the Freedom Charter, to all who lived in it. This is a rather different legacy than the one Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe alleged when he said recently that Mandela had treated “his whites” too leniently.

At the Monday ceremony, Sibongiseni Mkhize, CEO of the Robben Island Museum, observing the complementariness of the Mandela Centre and the Robben Island Museum, could joke, “I’m taking care of his island, [but] this centre only has to tell the story of one man. At Robben Island, we have to tell the story of 4,000 people and to ensure that complicated narrative is as inclusive and as holistic as possible… [While] telling the narrative of political prisoners is complicated, I look forward to working with this centre to help tell that narrative.”

In response, Sello Hatang, the centre’s new head, could say that his new task is to “take the Mandela Day campaign to parts of the world it has not yet been to” – and that “Mandela doesn’t belong to us or to this institution, he should be a global resource.” Moreover, Hatang continued, “The Mandela Centre is using memory to change the world for the better.” In that sense, the key tasks for this renovated centre, in its new phase, must deliver to the entire world an integrated information resource base on Mandela and his life, times and works; to convene dialogues and debate on social issues of the day, particularly “in the resolution of the toughest problems”; and to share Mandela’s legacy with the world via the broader, wider distribution of his political ethos. Or, as the outgoing head of the NMCM, Achmat Dangor, said of that special Mandela ethos, in quoting him, “‘bringing together those who agree is a chat; to have a dialogue, you must bring together those who disagree’ – speaks to the importance of proper debate at the centre.”

The challenge will come in the decades going forward, as the tangible impact of the physical presence of Nelson Mandela recedes back into history. Fewer and fewer people will then personally remember that electric moment in 1990 when he walked out into the sunlight and began immediately to pick up the threads of a tattered, angry nation; working to convince the millions that his famous statement from the dock at the Rivonia Trial when he pledged his life to work against racial domination by one group against another was a viable political philosophy and governing policy.

If that legacy has sometimes been soured by some of those who have followed him into politics; if it eventually became clearer that governing a famously fractious nation was much more difficult than imagining what should happen while he was still in prison; perhaps that is the fault of those who followed Mandela, rather than that of the dreamer himself. If that is the case, the mission and purposes of the Nelson Mandela Centre for Memory has much work left to accomplish – but there are many around the world will cheer it on as it goes forward. DM

* This article was written with the assistance of Jessica Eaton.

Read more:

- Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory home page

- Celebrating Nelson Mandela’s Legacy at the NMCM website

- Mandela daughter talks about her father at the AP

- Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom in cinemas this year at Business Day

- Repurposed Mandela Centre to inspire at the South Africa info (Brand SA) website

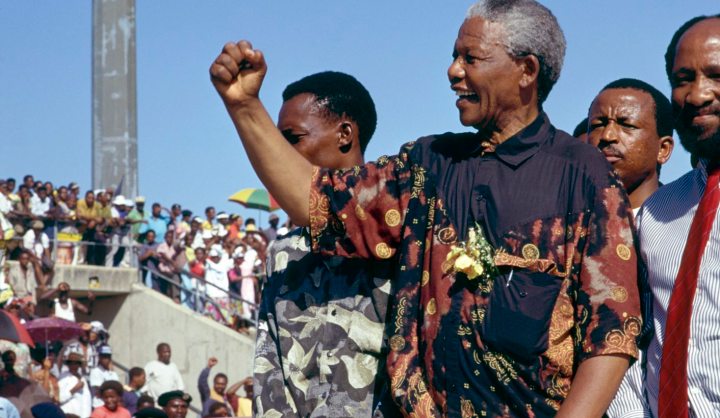

Photo: Nelson Mandela (Greg Marinovich)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider