South Africa

Unsafe House, Unsafe Job? The foul truth about living conditions at Marikana

At Lonmin’s platinum mine in Marikana workers have a new wage package and are back at work. But the terrible living conditions in which they exist persist, and a recent Bench Marks study suggests this squalor could directly compromise workers’ safety. By MANDY DE WAAL.

“The living conditions are terrible. The mining companies don’t invest in the communities and the people in Marikana live in shacks with no water, no drainage systems. We have to dig holes for toilets, and there is no electricity,” a Rustenburg miner told The Daily Maverick. “People live in very unreasonable conditions. It makes me feel terrible when I look at the mining company and how big it is. It is a world class group that makes so much money, but look at our community. Look at how we must live.”

Those appalling conditions are scrupulously documented in a two recent reports by the Bench Marks Foundation. And one of the studies makes the case that the workers’ appalling living conditions directly impact their safety on the job.

The Bench Marks report said Lonmin had outlined steps to reduce fatalities and injuries, but that these efforts stopped well short of referring to the living conditions of workers and how these conditions impacted worker health and safety.

Six Lonmin workers died in 2011, according to Lonmin’s sustainability report. Lonmin chief Ian Farmer writes in the documentation that “the passing of six colleagues during the year is completely unacceptable. Our sincere sympathies and support are extended to the families, co-workers and friends of these employees. We initiated a number of safety stoppages to give the business a serious message that these events must be eliminated.”

If Farmer was truly sorry about the mining deaths, perhaps he would have done something meaningful about their living conditions.

Lonmin’s sustainability report states: “We need to create a culture of safety, a set of shared beliefs about safety, within our organisation. We identified that the stressful, unsafe living conditions of many of our employees contributes to unsafe behaviour in the mining environment. Lack of sleep, poor diet, abuse of alcohol or drugs, or not respecting the inherent high risk environment of mining all contribute to accidents and fatalities. We need to find ways to improve the environment for our employees, both at work and in the broader environment, so that they are encouraged to foster a culture of safe behaviour.”

Photo: Sewerage in RDP settlement in Marikana overflowing. (David van Wyk)

But if you’re living between sheets of corrugated iron and your kids are wading in filth, how can this “foster a culture of safe behaviour”? Perhaps Farmer would do well to visit other mines in Africa (in Zimbabwe no less) to view operations were workers live in reasonable conditions and where safety records are world-class.

Lead Bench Marks researcher David Van Wyk believes the best circumstantial evidence for a link between safety and living conditions comes from Mimosa mine and Ngezi Mine in Zimbabwe, both of which are jointly owned by Impala Platinum and Aquarius Platinum. “Both mines have 100% literacy, both mines build proper (not RDP) housing for their mine workers, and neither use labour brokers,” he said.

Van Wyk also said the Zimbabwe mines don’t employ migrants, which can be safer as contract workers are often not properly trained and often live in poor accommodation. Partly as a result, he said, “the safety record at both mines is comparable to that of Canada and Australia.”

About a third of the workers at Lonmin’s Marikana mines are contract workers.

In its response to the research, Lonmin worked hard to discredit van Wyk.

“There are factual inaccuracies within the Bench (Marks) report and the company doesn’t agree with all the findings,” said Lonmin spokeswoman Sue Vey. “Lonmin does acknowledge, however, that there are certain areas in which it could be doing better. This is a challenge faced by the entire mining community and requires the co-operation and involvement of many parties.”

Vey said Lonmin estimates that approximately 50 percent of people living in a 15-kilometre radius of its mining operations were housed in informal dwellings with little or no access to basic services.

“In 2011, Lonmin converted 26 hostel blocks into 542 bachelor and 104 family units and saw 179 employees become owners of homes sold through the Marikana Housing Development Company,” she added.

Another report by the Bench Marks Foundation enabled the Rustenburg community to collate their own account of the “suffering and hardship” they endure because of mining practices in the region. The report detailed a legion of adversities faced by people living in towns like Marikana.

These hardships included air pollution; bilharzia found in streams close to squatter camps and no bilharzia warning signs; noise and destruction to property because of mine blasting; a lack of communication between the mines and communities; and in particular the seepage of sewage from the Lonmin mine settlement into nearby streams.

Bench Marks said the sewage problem at Marikana was caused because Lonmin workers are given a living allowance which isn’t enough to cover accommodation, food and transport. The result is that people in the Marikana settlement rent out rooms or enable miners to establish squats, which puts a massive strain on the sewage system.

“The mining companies are very dishonest in the way they deal with communities,” said van Wyk. “The community has been complaining for the last five years. They have complained to Lonmin and they have complained to the local government but nothing has been done,” he said.

The Bench Marks survey of Rustenburg mines sketches a scenario reminiscent of the Apartheid days, when miners lived in compounds. John Kane-Berman, CEO of the Institute of SA Race Relations, recently wrote about what living conditions for miners were like back then. The account is eerily familiar.

“Compounds were dreadful. Men slept in three tiers with their clothes suspended from string across the ceiling. Lavatories had no seats or doors. Privacy was non-existent. Even the newer compounds were bleak. The worst feature was that black miners were unable to bring their families to live with them, even if they wanted to,” he wrote.

Well over a century ago the man who helped create De Beers would say: “Africa is lying ready for us, it is our duty to take it.” A racist colonialist, Cecil John Rhodes, would establish the first black reserves and would close down schools near these work camps for fear that education would turn labourers into agitating revolutionaries.

Speaking of mining labourers in the late 1800s, Rhodes said: “Nine-tenths of them will have to spend their lives in manual labour, and the sooner that is brought home to them, the better.”

The big question is: how much has mining labour practice in Rustenburg changed since then?

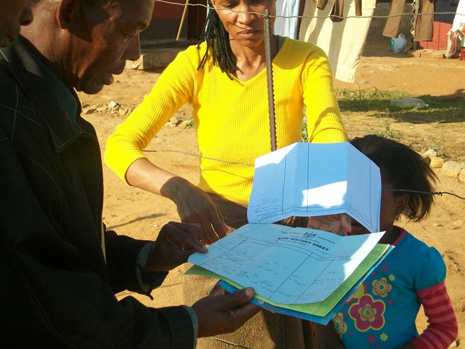

Photo: Mother showing a Bench Marks monitor the doctors reports for a young child showing her suffering from the chronic illness because of the overflowing sewerage. (David van Wyk)

Van Wyk said despite a commitment to sourcing local labour, Lonmin sources much of its labour from outside of Rustenburg.

This was borne out by a Lonmin miner. “The mines, they go to the Eastern Cape and they speak to the chiefs there and get uneducated people to work for them. Some of them they don’t even have schooling but they go to the mines, they sign the papers, and then they have no choice. They work in the mines, they live in the shacks. That is their life,” the miner told The Daily Maverick.

There’s an interesting series of quotes at the beginning of van Wyk’s research report that speaks to the relationship between mine management and the mine workers. The quote comes from some banter that took place during a break in conflict resolution discussions between a mining company and a community in Rustenburg.

Mine manager: “Our relationship with the community is like a marriage, we must not get third parties to spoil our relationship, when there are problems in a relationship we must try and resolve them. The government through its intervention is acting like a marriage councillor, but we must resolve our issues ourselves.”

Community member: “This marriage you are referring to is problematic, because we woke up one morning in 2008 to find this mining company in our bed, we were violated because there was no consultation, it was sex without consent – it was rape.”

Mine HR manager: “Hau bana, there is nothing like rape in traditional weddings or marriage, the wife has to do what the husband wants….”

Cecil John Rhodes would have been proud. DM

Read more:

- Lonmin mining communities: A powder keg of inequality in Mail & Guardian;

- Marikana: The strike might be over, but the struggle continues in Daily Maverick;

- Dire living conditions in Marikana ‘a crisis’ on IOL;

- The Marikana action is a strike by the poor against the state and the haves by Justice Malala in The Guardian.

Main photo by Kyle de Waal.