There’s a rather offensive trend swirling among the nattering class that has gained momentum over the past decade or so. It is tightly interwoven with a rather pernicious type of identity politics. And so, Pari passu with the search for, and (re)assertion of identities (a crude identity politics), there has risen loaded charges of cultural appropriation, as if culture is static over time, and as if culture is the sole property of a single group of people.

This trend is part of the rise around the world of (a distinctly right-wing) ethno-nationalism, and a search for purity from Narendra Modi’s India, to Donald Trump’s America, where people like Richard Spencer celebrate white power and superiority. As for the left, and on the face of it, charges of cultural appropriation seem to be part of the left’s embrace of pernicious postie posturing, coupled with a type of closure, which presents concepts or practices as complete and, therefore abgesichert – secured from all scrutiny, questioning and evaluation. This has left most folk with deep-seated commitments to leftist principles, or driven by emancipatory principles, feeling somewhat befuddled….

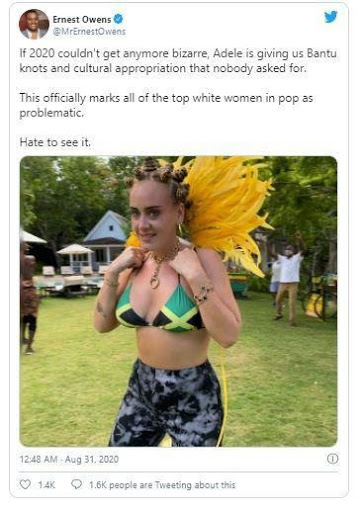

Most recently there appeared a picture of the British singer Adele dressed in a bikini top in the colours and design of the Jamaican flag. Adele was criticised for having her hair done in “Bantu knots”, which, it was claimed, amounted to cultural appropriation. I’m sure there are spokespeople for Adele, as there are for the Bantu and their culture. No pun intended, but I have no skin in the game. This is not the first, it is not the only, and it certainly will not be the last time that a person will be accused of “cultural appropriation”. The absurdity does not start or end with white people appropriating “non-white” culture.

Recently in Malaysia, a social media personality, and “influencer”, Mira Filzah, a Malay model chose to adorn herself with Indian clothing, jewellery and henna on her hands, apparently as a sign of appreciation, and according to Filzah, it was done in homage to Bollywood films and music. Filzah’s Instagram account was plastered with young Indian-heritage Malaysians who were “uneasy,” and invoked the term “cultural appropriation”. For what it’s worth, my late mother and sisters are not Indian, and often used henna or “mendi” on their hands. My father used it in his beard…

Before I start to tug at the loose strings of this concept, I should probably lay down some conceptual and historical issues about culture, and the great historical injustices against indigenous people around the world, whose customs and traditions run deep. A very basic meaning of the term “cultural appropriation” refers to taking from a culture that is not one’s own, the intellectual property, cultural expression, artefacts, history and ways of knowledge, and using it for one’s own benefit or pecuniary gain. This gain took a wicked turn with the stripping of ancient structures from Egypt, which ended up mainly in European private collections and museums.

For example, early in the 19th century, sculptured marble friezes were removed from the Parthenon. These “Elgin Marbles” were sold to the British Museum in 1916. There are very many examples of European “explorers and adventurers” removing valuable artefacts from places as far apart as Angkor Wat, Egypt, Mexico, China, Yemen, Iraq or Peru, and that have become part of the “possessions” accumulated by Europe’s wealthier classes. These things are never quite as simple as they seem; the historical theft has to be acknowledged, but so, too, should domestic theft and vandalism; from the Taliban’s destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan to local theft of relics and artefacts from Angkor Wat.

These may be placed in a separate category. It is, however, the theft, and the wilful destruction of the culture of others, often under the precept that indigenous people are unable to take care of valuable things. The argument put forward by the European world was that the stolen artefacts “were being taken to be put in museums and preserved for posterity. The sub-text, however, was that the indigenous were incapable of looking after their own cultural heritage while colonial cynics would counter that such arguments were contrived simply to justify the theft of artworks worth millions of dollars.”

The Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention, adopted in 1999, specifically defines “attacks on property under enhanced protection, using such property or its immediate surroundings in support of military action, extensive destruction or appropriation of cultural property covered by general protection, making such property the object of attack, and theft, pillage, or misappropriation of property under general protection” as a serious violation and in violation of the protocol. If anyone took that protocol seriously, the original Mostar Bridge would still be standing, and US soldiers who stole artefacts in every country they invaded, would be on trial.

We should, then, draw a clear distinction between theft and destruction, or appropriation of cultural artefacts for financial gain and someone dressing in a toga, or tying her hair in “Bantu knots”, or a non-Indian Malaysian putting henna on her hands. The former are clearly cases of vandalism, theft, destruction and rapine. If we include all cultural exchanges reflected in the second example, cultural appropriation is in a bog, in which it’s difficult to swim and easy to sink – and drown. As mentioned, it’s all rather befuddling.

We know that Adele is not allowed to shape her hair in a way that is not shaped by her cultural moorings in London. We also know that the journalist Afua Hirsch is allowed to leave her London moorings, embark on a search for her African identity, and (re)adopt them – if she so chooses. I have some sympathy for Hirsch’s position, as I too, am interested in my family heritage, which was shaped by the first Southeast Asian slaves that were brought to the Cape by the Dutch colonists from 1652 onward. But that does not shape my culture – which is fairly secular, cosmopolitan and dynamic.

Let’s come together, but stay apart…

Later this month, South Africans will celebrate Heritage Day. It does not matter how it is spun, it is the day in which Zulus go to their Zulu family, Xhosas go to their Xhosa family, Jews go to their Jewish family, and well, us ideologically or religiously lost bandits find things to do with our time. The point here is that with Heritage Day, we recognise that each person, or group of people, has a cultural identity, and must be given time to “go and celebrate their culture with their people”. Well-intended an initiative as it may be, it is somewhat strange; to bring people together, and establish some kind of social cohesion, and build trust in a new democracy, we have to separate people by an iniquitous racial classification system, and promote a retreat into “cultural” identity under the guise of “heritage”.

By way of example. As a coloured person, so classified by the state, on Heritage Day I can travel to Eastern Cape with the Xhosa love of my life, but I can’t dress in local (Xhosa) garb, nor can I join the family in (isiXhosa) song, because that would be cultural appropriation. It’s not always the case. I have been to several seders on Passover, and celebrated High Holidays with Jewish families, and was most welcomed. I even wore a yarmulke, and nobody complained. Also for the record, I have a very deep appreciation for Yiddish culture, and no Eastern European has accused me of “cultural appropriation”.

Let’s come back to Adele’s “Bantu knots” and what it may mean. I will use an example I know best. My own experiences and encounters. I will, for the first time, and for the sake of this discussion, define myself as rootless cosmopolitan coloured. As a child I was immersed in a quasi-Malay culture (historical, genetic and familial evidence confirm that I am of Malay heritage), I grew up in a coloured township, called myself black, and travelled the world where I learnt smatterings of languages from around the world.

I have eaten, sung and danced with people in Manaus, Buenos Aires, Georgetown (Guyana), Colombia, South Carolina, Reykjavik, Tromso, London, Glasgow, Paris, Berlin, Novi Sad, Palestine, Abu Dhabi, Mumbai, Rangoon, Kuala Lumpur, Taipei, on an island in the Sulu Sea, and very many other places. I was welcomed everywhere, and acquired or adopted cultural habits or traits everywhere. In Mexico, I learnt to refer to men as Querido, and women as Querida – which basically translates to “darling” – without romantic connotations. Whenever I visit a Spanish country, I use it, and whenever I am among fellow Arsenal supporters in North London, I slip seamlessly into a type of cockney…. Along come my comrades on the left, the ugly (expletive deleted) posties, and the wokemeisters.

What’s a good coloured to do?

Again, using my own experience (so I don’t melt any snowflakes) I am now supposed to behave like a good coloured, but I have no idea where to start. What I have learnt, from the ugly (expletive deleted) posties, and the wokemeisters, is that I cannot sing and dance like a Zulu, a Greek, or a whirling dervish. My shaven head makes me look a lot like a Glaswegian skinhead. I eat way too much French and Italian cheese and salami. Feijoada (a Brazilian black bean stew – with a few alterations) and a beef rendang (Southeast Asia) are my favourite dishes. I would do anything for a good cevapcici – with a few tasty changes. I like Indian and Southeast Asian food.

The Swan Theme of Swan Lake is probably the most beautiful piece of music ever written. Edgar Degas and Toulouse Lautrec are my favourite painters. Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekov and Fyodor Dostoyevsky are among my favourite writers and, well, when I was a child, I knew only jazz (from the United States). I love movies (initially from the US), and only later in life developed a preference for French jazz, and for European and Russian film. I love wearing a sarong, and used to enjoy wearing my grandfather’s kaparangs.

A photo taken in a Javanese madrassah in the Dutch Colonial period. Left-hand corner of the picture shows two pairs of wooden Javanese clogs. In Cape Town, these were called kaparangs and could be found in many old masjids. (Source: Kaparangs – Aljaamiah Academy)

Although I am what in the lexicon of apartheid and the African National Congress, is considered to be a coloured, and “non-African,” I still use Melayu words and phrases like Terima Kasih (thank you) Selamat Jalan (travel safely), and Selamat Hari Raya Puasa (Eid Mubarak) – most of which have been handed down by my forebears over centuries. But none of this defines me, and nor does it make me the curator or owner of Malay heritage.

As it goes, I follow the politics, arts and culture from almost all countries east and south of Europe (a conscious decision to break from Eurocentric thought and reportage as the mainstay of my daily consumption), and I am especially interested in the vernacular architecture on the steppes of Asia, and that of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Sometimes I listen to klezmer music, and sometimes I listen to Indian, Chinese, Malaysian or Malian music. All of it just broadens my “cultural” and intellectual horizons. I dress in mainly Western clothing, and almost all the technology I use daily has its immediate origins in the sciences and technologies pioneered – at least as far as I know – by Europeans.

Unless, of course, televisions, refrigerators and computers – in their 20th-century incarnation – were designed and manufactured by technologies in Africa, Asia, Latin America or the Polynesian Islands. To the extent that these things all constitute a culture, what then, should my culture be? While that question is rhetorical, and at the same time provocative. There is this thing called syncretism which enters the discussion. The last time the term was used was when I asked a political leader why he was so opposed to everything non-African, but he liked his luxury German automobile, and Breitling watch. He resorted to insults, name-calling and threats of violence. Biasa lah! (Malay for that’s the way things are.)

All of this beggars the question, at what point is cultural cross-pollination “syncretism,” and at what point is it “cultural appropriation”. The answer in South Africa is easy. When Johnny Clegg died last year, Twitter was aflutter with accusations that he became wealthy by appropriating black culture. Paul Simon was similarly accused of benefiting from African culture with his album Graceland (although he did use Brazilian musicians in some of his other work, but we are not allowed to mention that).

If you ignore the frippery and chauvinism, cultural appropriation is actually a real thing. In its most rapacious form it is the theft of cultural artefacts for personal pecuniary gain. The problems emerge when one culture is imagined to be more superior than any other, when one culture is foisted on people against their will, and when people assume that culture is static, and eternally so.

Of course, none of this means people are not able to “practice” their culture any which way they wish. It simply means that culture is, necessarily open, dynamic, that it changes in places. It is appropriated and redeployed – the way the English language is appropriated in, say, Jamaica, and redeployed. Edward Said once wrote that there are many Islams, and simplifying the Islamic religion, or placing it in a fixed category, sealing it off, is almost impossible. Indeed, every Arab country has a different set of customs and traditions. As much as you can call someone an African, it’s incredibly difficult to claim that there is a single African culture. The same would apply to Europe and Asia, for that matter.

As for Adele and her “Bantu knots,” or Filzah and her henna; they should be able to make of culture what it is meant to be. Dynamic, open to change and transformation, available to anyone and everyone. To paraphrase Eric Hobsbawm on tradition: Customs which claim to be old (and deeply ingrained in communities) are often quite recent in origin, and sometimes invented.

If I take this further: “It is the contrast between the constant change and innovation of the modern world and the attempt to structure at least some parts of social life within it as unchanging and invariant, that makes the ‘invention of tradition’ so interesting for historians of the past two centuries,” Hobsbawm wrote in, The Invention of Tradition.

In closing, and admittedly, I have no answers, daring or revelatory conclusions; this evening I had dhal for dinner, tomorrow, I will make Umngqusho, and for health reasons, I will refrain from drinking Umqombothi. I trust no one will be offended, or call that cultural appropriation. Dhal and Umngqusho do not make me anymore, or any less, coloured, Malay, African, or whatever people in power deign to call me in this befuddling world of identity politics, and the policing of culture and invented traditions. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider