DINING IN A WAR ZONE

Fish and hope are on the dinner menu in Ukraine

Pull up a chair and let’s order some fish and pickles. In Odesa, the fish is fresh, the tourists are gone and the locals are holding out for a return to better times.

In times of war, food is synonymous with survival. In a slow, protracted conflict, it becomes a matter of resilience. In Ukraine, good food is as plentiful as the air raid sirens, nowadays only heeded by visitors to the country with strict security minders, like ourselves.

But it’s a near-daily reminder that the war is still hot, even if life goes on in those towns and cities not on the frontlines. Sometimes, though, a deadly drone slips through Ukraine’s air defence systems and strikes five storeys out of the side of a Soviet-era apartment block, like it did last Saturday morning, shortly after midnight. Twelve lives were gone, as they slept, the worst loss of life in Odesa since Russia’s full-scale invasion two years ago.

“We think the Russians should answer about that hit,” the mayor said later in the day. A strong whiff of vodka mingled with that of the calming valerian drops given to family members anxiously waiting as rescue workers searched through the rubble for those still missing.

Overwhelming was the smell of the insides of home, of food scraps, onions, on the verge of going off, so ordinary that it throws you completely.

Odesa is a main Ukrainian port city on the Black Sea, side-eyeing Russian-occupied Crimea to the east and looking over its shoulder to the west to Transnistria, a separatist pro-Russian enclave sandwiched between Ukraine and Moldova.

Fish is what you’ll find here, even if you’re no longer sure that the Black Sea exists, as the military has blocked access to most strategic viewpoints. Even the famous Potemkin steps, named for a scene in Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 classic, are damaged and closed, a drive-by attraction only, no photos.

Tyulka is the name of a fish, and of this restaurant. It is hidden in plain sight, across from the Transfiguration Cathedral where a missile last July struck a gaping hole next to where the altar should be.

Tyulka restaurant, Odesa. (Photo: Carien du Plessis)

The aim of the restaurant’s founder, Volodymyr Bulgakov, was “to make the focus Odesa Jewish cuisine, and to cherish the spirit of Odesa Jews, and the small talk over drinks, this attitude that Odesa has,” the waiter, Olga Potapova, says.

She’s been there 12 of the 14 years of the restaurant’s existence. It’s an old and established Jewish community that has lived here since the 16th century, but nowadays it’s shrunk to a single digit percentage of the total population.

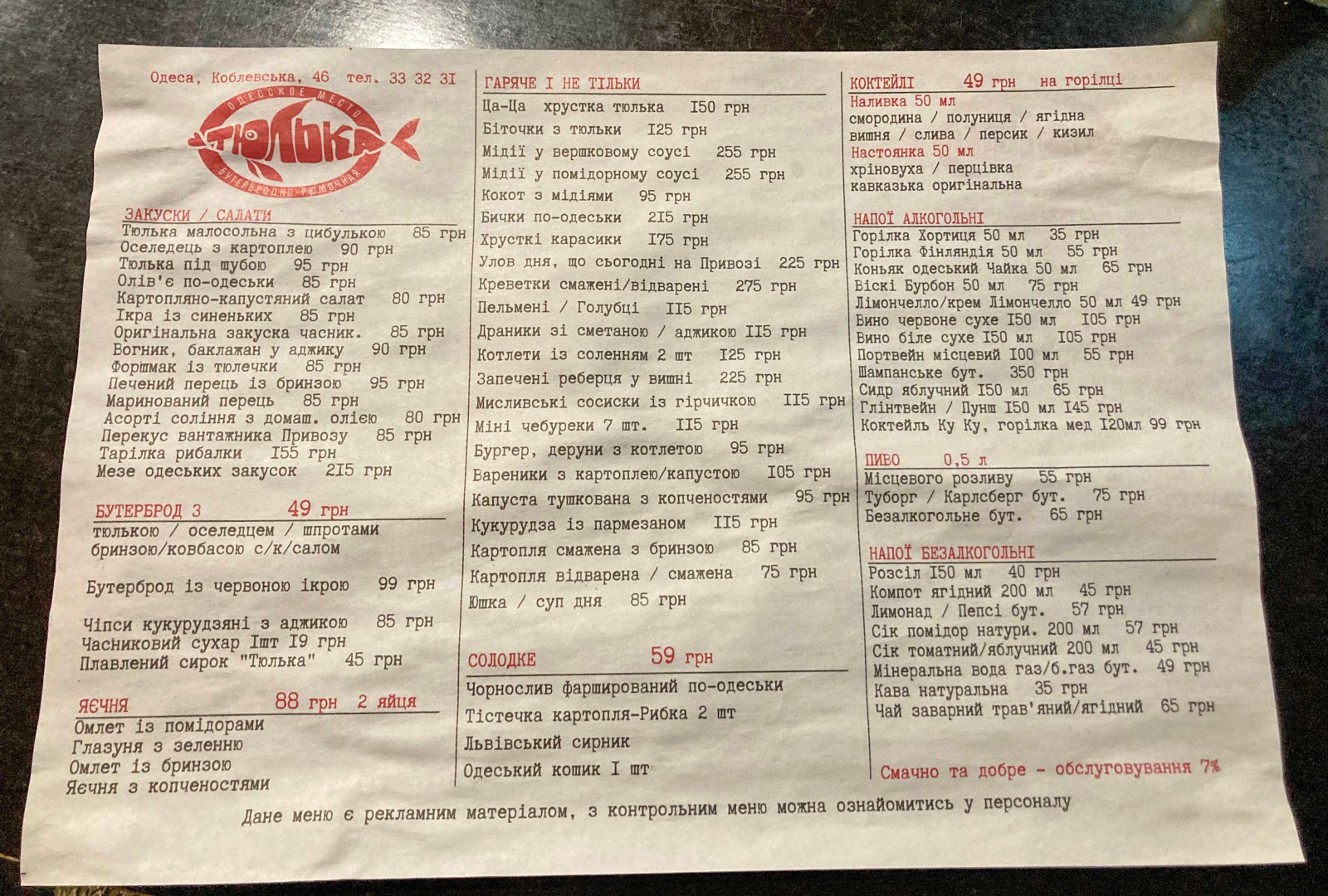

Having a translator to hand helps when choosing from the menu. (Photo: Carien du Plessis)

Dima, the fellow hack who brought us here, translates. Just as well, because the menu is in a dense Cyrillic, no English reprieve, and my Russian’s gone rusty from lack of practice, and my Polish minder, N, never cared for the language forced on him at school, many moons ago.

Tyulka fish, sour cream, pickles and courage are on the table at Tyulka restaurant in Odesa. (Photo: Carien du Plessis)

Dima’s a foodie and loves the restaurant’s signature dish, tyulka, so much that he carried a portion of the small salted herring-type fishes back to Kyiv with him. The weather’s cold and it stayed fresh.

A brief back-and-forth with the waiter eventually settled us on the restaurant’s favourites: tyulka lying three-a-side on a slice of dark brown bread spread with cream cheese, a halfmoon of tomato at their tails, with a sprinkling of spring onions; tyulka fried with egg, like omelettes; tsatsa, small little fried fishes eaten whole and dipped in sour cream, and forschmak, which could send you close to tears longing for the home in Odesa you always wanted to have.

“I cannot share the recipe of the restaurant,” Olga predictably says, “but usually it’s herring, and sour apples from the jar.” It’s pickled apples! Dima adds to the translation, his eyes wide with enthusiasm and his arms embracing the thought. Also, boiled eggs and bread go into the mixture. “And love,” Olga smiles.

It’s a recipe born of hardship, and now so delicious that it makes you want to stay here.

Aquamarine hues reflect the seafood theme at restaurant Tyulka. (Photo: Carien du Plessis)

There is also a menu item which translates into “anything we could find from the Privoz Market”. The place sells anything from fish, fresh fish, smoked fish and fish to pickles, fruit, veggies and as many different cottage cheeses as the hands that make and sell them.

Earlier in the day, at Privoz, I asked Dima to convince a woman to sell me some cottage cheese in a blini (pancake), because that’s how the babushkas sold it on the Trans-Siberian train I travelled on when I was in this part of the world in 2000.

She sold it to us like that, as an exception, treating us to extra smetana (sour cream) on top. Some of the sellers here don’t like tourists, like the stout, red-faced woman selling redcurrants and berries who shooed us on so she could continue with her life.

Tyulka gets its fish from this market. “It’s a flavour of Odesa, and all the fish in the restaurants come from Privoz,” Olga says.

Tyulka on a slice of dark brown bread spread with cream cheese, a halfmoon of tomato at their tails, and a sprinkling of spring onions. (Photo: Carien du Plessis)

When the war started, fishing stopped, but Tyulka stayed open.

“We used frozen fish,” Olga says, “but then the fresh fish gradually came back.”

Parts of the Black Sea remain heavily mined, but the fishers apparently find a way.

For now it’s mostly the locals who visit the restaurant.

“We lost tourists from the country where we don’t need them from,” Olga says, without mentioning neighbouring Russia’s name.

“The first year was very difficult before everyone adapted, but now we see a revival and the local tourists are coming back.”

These are mostly from the west and north of Ukraine.

Still, cities and towns have visibly emptied. About six million of the country’s 43 million have fled the war and are still outside Ukraine, according to the UN Refugee Agency’s February 2024 figures.

There are also the funerals and the fighting, says Alyona Symonenko, chief brewer of Hoppy Hog, a family beer business in Odesa that started after the war.

“One of our best, most wonderful bartenders here, Tomasz, he joined the military. And fewer of our military friends come here, because they’re all either injured or killed in action, or they are holding the frontline without any rest, without any rotation.”

Mostly those in their early 20s, too young to be conscripted, or the much older crowd, who cannot go to war, now frequent the establishments.

International tourists, though, have mostly dried up. The Odesan-bred deputy CEO of the Ukrainian Sea Ports Authority, Dmytro Barinov, remembers the time before 24 February 2022 fondly.

“Before the war there were thousands of guests, big cruise vessels from worldwide,” he says.

“Every day there were hundreds of buses and guides. They bring tourists, going through the city centre, all bars were filled, shops, cafes, all full of tourists.”

It’s a problem, this, for people big on hospitality, to have nobody to heap it on.

“That is why we try to survive, that is why we hope that after our victory, we return to this passenger market. We have lots of sites with good food, nice beer,” he says and smiles slightly.

Hours after leaving Tyulka on Monday night, an air raid siren tore through the beginnings of our dreams and assembled us in the shelter, which is also the hotel cellar which hosts a local brand of Odesan wine.

Three hours later, shortly before 3am, we returned to bed to a brief rest before departing for Kyiv, but one day I hope to come back here again, to find the tyulka and the tourists. DM

Carien du Plessis is in Ukraine for a reporting trip on the invitation of Zinc Network. She works for The Africa Report and occasionally contributes to Daily Maverick.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.