A MASTERPIECE

Fifty years later, ‘The Godfather’ remains a landmark in cinematic history

Through its depiction of the Mafia, its drama, sweep, exploration of power and illegality, its rendering in all its complexity of a community, a family, and of the structure of American society, ‘The Godfather’ is a masterpiece.

When Francis Ford Coppola first glanced through a novel by Mario Puzo, he thought it “a rather sensational, sleazy crime novel”. Not long after, he made The Godfather, one of the greatest movies ever made.

There are not many candidates for best film ever made: Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein), Citizen Kane (Orson Welles), Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray), Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa)… the making of The Godfather was a landmark in cinematic history because of its depiction of the Mafia, its drama, sweep, exploration of power and illegality, but also its rendering in all its complexity of a community, a family, and of the structure of American society.

While the focus here is on the movie, it is inseparable from its counterparts, the second and third episodes of the saga, which together make up the kind of span covered by the miniseries of today.

The Committee on Organized Crime was convened in the US in 1950, with televised hearings, and another committee in 1963 looking into organised crime also received nationwide attention. Paramount studio boss Bob Evans was convinced interest in the Mafia was growing. Puzo, heavily in debt, submitted 60 rumpled pages to Evans, who bought the rights for $12,500 (more or less R215,000) to turn it into a movie.

Earlier treatments of the topic had failed at the box office because, Evans thought, they were not made by Italian-Americans. He was convinced the movie “must be ethnic to the core. [Y]ou must smell the spaghetti.”

Coppola, 30 at the time, had written the Oscar-winning screenplay for Patton, and just made a decent film, The Rain People, which was a box office failure. He owed the studio money but he was reluctant to make a movie that glorified violence, but producer Albert Duffy convinced him and he took on the project.

He reread the novel, this time finding it was “the story of a family, this father and his sons; and I thought it was a terrific story, if you could cut out all the other stuff.”

Aspects of production

Puzo’s novel was a bestseller, selling more copies than the Bible, but he was finding it difficult to turn it into a movie script, so he got help from Coppola.

Filmed by Gordon Willis, the movie features scenes of every kind: assassinations, funerals, sick beds, baptisms, weddings, a blood-splattered horse’s head in satin sheets, all shot in a variety of shades and lighting. Darkness is deployed as frequently as light, submerging the viewer in the play of light and shade. Willis was at odds with Coppola about how the director wanted him to render the drama, but eventually came round to his sensibility.

The music was at times moody and dark, but also light and frivolous. Nino Rota had written the music for a string of Fellini movies, and was an accomplished and innovative artist of musical soundscapes.

Composer Nino Rota, who wrote the theme for the film ‘The Godfather’, pictured at the piano, circa 1972. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

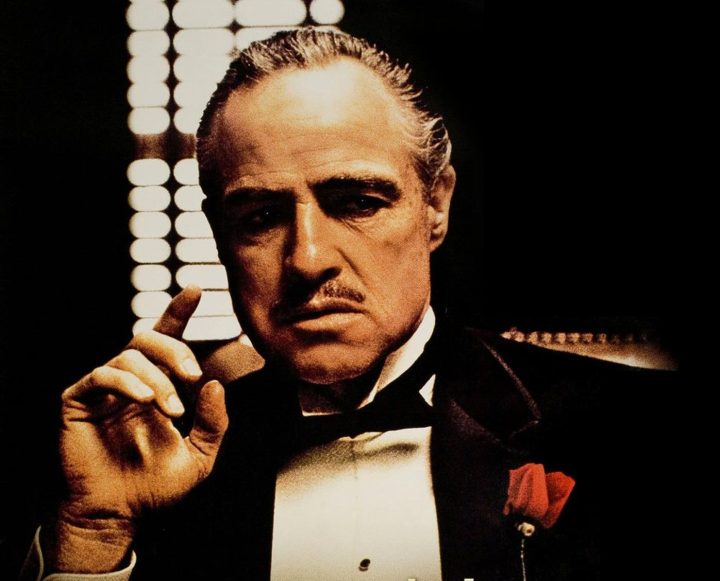

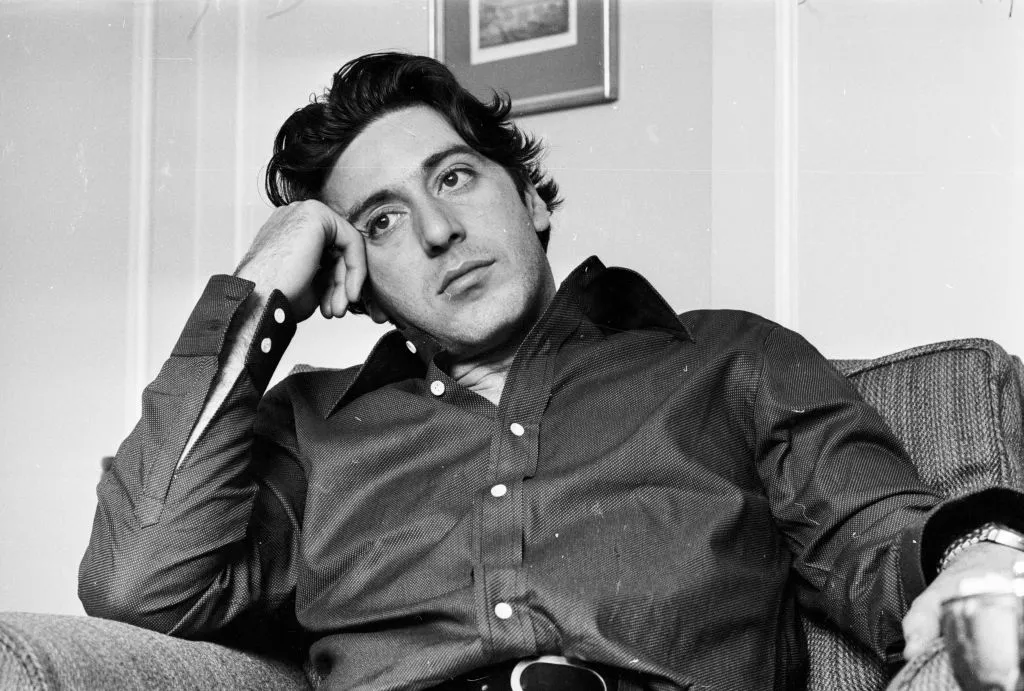

The cast contributed to the film’s greatness: Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Dianne Keaton, Robert Duval and James Caan were the best known. Brando appeared after a lull in his career, which the film resuscitated. Pacino played the main character with an intensity that is frightening, and Keaton appeared in one of her most serious roles.

25th March 1974: American actor, Al Pacino, in London. After making his name in The Godfather and Serpico, he was finally awarded the Best Actor Oscar for his role in Scent of a Woman. (Photo by Steve Wood/Express/Getty Images)

The remaining cast is a wonderful mix of characters, exuding an authentic Italian, Sicilian flavour. Oddly shaped men and women, with distinctive faces, gaits, ways of being; this was a world far, far from the superficial poise of smiley Hollywood optimism.

Drama in the Godfather’s household

Everyone knows, by now, the story: the reign of the godfather, his gradual demise as Mafia families engage in a struggle for dominance, and the accession of his third son to the seat of power.

The Mafiosi are gangsters, but they are more than a gang. Besides being larger and having more resources, they are bound by codes of honour and loyalty, a veritable object of anthropology. Nevertheless they are parasites, living off protection money, gambling, prostitution and drug running. And yet Vito Corleone accumulates respect and power by killing other parasites. He refuses to get involved in drug running, for moral as well as pragmatic reasons, initiating a mob war.

“I believe in America, America has made my fortune,” are the first words spoken in the movie’s wedding scene, with an undertaker pleading with the Godfather for justice for the two men who raped his daughter. “I want them dead,” he says. “You didn’t ask with respect, you don’t offer friendship. You ask me to murder for money? What have I done to deserve such disrespect?” The Don agrees to administer justice after the undertaker recognises him as “Godfather”. He is able to right wrongs the justice system is unable to.

He famously gets a godson a Hollywood acting gig by making a recalcitrant director “an offer he can’t refuse”, having the head of the director’s prized $600,000 horse planted in his bed. Not only is the Mafia able to silently penetrate the mansion of a revered Hollywood doyen, but it has a stealthy presence in the heart of the global American entertainment industry.

The Mafia can exercise this kind of power because it depends on the corruption of the supposedly legitimate world, especially politicians who frequent their casino-brothels. They buy politicians, judges, prosecutors, police, union leaders and even journalists. In The Godfather Part III, Michael tells his estranged wife: “All my life I’ve kept trying to go up in society, where everything higher up was legal, straight… but the higher I go, the more crooked it becomes.”

Made up of “families”, the Mafia have a presence in all the major cities of New York, and a meeting of the families reveals the structure of the many-headed hydra. The Mafia run a fledgling state within a state, a feudal hierarchy with the benefit of motor cars and mod cons. It formulates policies, engages in long-term planning, conducts inter-family and interstate relations.

Coppola straddles time zones, modernity mingling with feudalism, but these elements are found in unexpected places: the family is feudal, but the recalcitrant movie director is also a kind of feudal lord in Hollywood – as is the Mafia, a set of warlords negotiating a balance of power. Modernism also figures in unanticipated settings: references to Clark Gable in rural Sicily, Beatle-like fan hysteria at the wedding, resort to PR and the media as part of Mafia strategy.

When considering whether to get involved in narcotics, the adopted Tom Hagen, consiglieri, tells the Godfather it is the industry of the future – if they don’t get involved the other families will and slowly acquire the means to buy their own police and politicians. “Then they’ll come for us,” says Hagen.

The services the Godfather renders inspire loyalty and reciprocity in his subjects, and when he requires payback it is readily forthcoming. Enzo the baker, who gets permission to remain in the US because of the Don’s intervention, visits the Godfather in hospital and risks his life to guard his benefactor. The undertaker too pays his dues by tending to the bullet-ridden body of the Don’s eldest son, Sonny. Favours are returned and offences repaid with vengeance. But vengeance is also forgone for strategic reasons, as when Sonny is killed.

But there is another sense of family that looms large in the movie, the traditional sense. “A man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man,” says the Don.

The family is sacrosanct, with a strict line between the inside and the outside, although there are border elements, such as Hagen, who retains his surname, yet is more or less inside; Carlo the son-in-law is admitted into the family, yet he is never really inside. The family must never be seen to be divided, and the Godfather warns Sonny, his eldest son, “never tell anybody outside the family what you’re thinking”.

Sibling rivalry looms large. Sonny arrogates the Don’s power to himself when the Don is shot, but his tempestuous nature ensures an untimely end. Middle son Ferdy is too feeble-minded and weak to succeed his father, but he wants more. Michael is the rebel, the individual, the at-first reluctant but chosen heir.

In the second scene, the Don refuses to take a family picture if Michael isn’t in it. Michael is his favourite, who the Don hopes will stay out of the family business and become a legitimate force, a senator in a world that excludes wops.

Michael’s story is the central thread: his transformation is from the college-educated soldier with military honours, the civilian and butt of jokes, to the new godfather. The transformation begins after the hospital scene, when the crooked cop assaults him, and it is completed when plans the murder of the cop and the drug dealer – he becomes the strategist and executioner.

When Michael kills the cop – a move no mere hood would dare to undertake – he uses the machinery of public relations to legitimise the murder, getting journalists on their payroll to write about the cop’s ties with organised crime, exploiting the sensationalism while winning public sympathy. “Police captain linked with drug rackets,” a front-page headline screams.

He effectively succeeds his father by avenging the attempt on the Don’s life. In Italy, his marriage is an affair of the entire village, the feudal world the Mafia emerges from. On his return from Italy his transformation is complete. His conversation with Kay is a key to his new worldview. He tells her he is now working for his father. When she questions his link to a business that relies on murder that he once disavowed, he says: “My father is no different than any other powerful man. Any man who’s responsible for other people, like a senator or a president.”

Michael is given the gift of his father’s support, appointed to replace him. The intimacy between them is exceptional. No Oedipal tensions here, just pure trust and love. But Michael proves to be nothing like his father, far more ruthless than he has to be. He accepts his sister’s plea for him to be godfather to her son, knowing that on that same day, he will have the father of that child killed. And while he presides as godfather at his nephew’s ceremony, he has the heads of the other five families killed, being the Godfather in the other sense of the word, the Don, the dispenser of life and death.

He wrings out a confession from brother-in-law Carlo after assuring him: “You think I’d make my sister a widow?”; and then has him killed in cinematically spectacular fashion, strangled in the front seat of a car, his writhing feet smashing through the windscreen, revealing the worn soles of his shoes.

This is a strictly patriarchal world, where men decide and act and women play support roles. “Women and children can be careless, but not men,” the Don advises Michael just before he dies. When in the village Michael is struck, as if by a bullet, by love, he is told: “In Sicily, women are more dangerous than shotguns.”

“Don’t ask me about my business, Kay,” Michael tells his wife when she asks if he had Carlo killed. He lies to her, and in the final scene of the film, she leaves the room to have the door closed on her as the capos come in to pay obeisance to the new Don Corleone, and as she witnesses the scene unfold, she realises he lied to her. Gradually, in The Godfather Part II, she is one of the few who come to see the horror of his persona.

The Godfather as tragedy

The whole panoply of weddings, funerals, killings and negotiations is held together by a thread of intrigue about who is in power and how he might be toppled.

Unlike most gangster movies, with their foregrounding of violence, there are many moments of warmth and kindness. The Mafiosi are humanised. The Don comes across as strong but fair, even compassionate, a man of his word, who uses violence only as a last resort.

Audiences were captivated by the characters, especially the Don, saturated as he was by Brando’s charisma. Instead of offending the morality of the viewer, he, more often than she, saw a role he would very much like to inhabit. People went around performing passages from Brando’s dialogue, verbatim.

The movie showed what crime can achieve when it is organised, a social structure with a specific purpose, an accepted hierarchy, a division of labour, a set of policies, an infrastructure in the service of a tribe. Far from being a moralistic warning about the horrors of crime, the movie was a masterclass in how to conduct criminal activity, with gangs everywhere attempting to replicate the example.

A tale of power, corruption, murder, loyalty, betrayal, revenge, estrangement, family, sibling love and rivalry, and crimes of every sort, it is the primaeval nature of the film that enthralled audiences, as well its artistic rendering by Coppola.

The structure of the movie was taut, economic and aesthetic. Each of those services requested in the opening wedding scene plays a part in the war that follows. Everything has a consequence as decisions play themselves out. The entire series unfolds the stories of Vito Corleone, the Godfather, and Michael Corleone, who transforms into a ruthless capo, ultimately making for an epic tragedy. Fifty years later, its influence persists. DM/ML

Comments - Please login in order to comment.