Book Excerpt

Denis Hirson reflects on 1960s Joburg in his memoir My Thirty-Minute Bar Mitzvah

Denis Hirson’s memoir My Thirty-Minute Bar Mitzvah is a sensitive, poignant and beautifully written account of his thirteenth birthday, set against the menacing backdrop of 1960s Johannesburg.

South African author Denis Hirson, who has lived in France since 1975, remains true to the title of one of his prose poems: ‘The long-distance South African’. His work, both poetry and prose, is concerned with the memory of the apartheid years in South Africa, and includes the bestsellers The House Next Door to Africa and I Remember King Kong (the Boxer). My Thirty-Minute Bar Mitzvah has echoes of a detective trail as Hirson explores the wider ancestral and political strands of his story. Read the excerpt.

***

One

Of course I had a bar mitzvah.

It took place on a cool, crisp afternoon in Johannesburg on the day I turned thirteen, towards the end of August 1964.

There were three other people present, or five, depending on whom one chooses to include. Five, let’s say, the men divided from the women according to the time-worn tradition.

There were no photographs, no gifts bought or made for the occasion; no singing or elevating sound, unless one counts the bellyfuls of steam rising up from the iron grid between the flagstones of the pavement across the road. But the steam hardly made a whisper and, anyway, I cannot be sure that I noticed it at all. The ceremony lasted precisely thirty minutes, as had been agreed on well in advance, not a second longer. One of the people present announced the end in a voice as blunt as it was relieved.

Did I cross the threshold into manhood on that day, as one is, at least symbolically, supposed to do? I don’t know. I doubt it. But I did at least in the wake of this event begin to understand a number of things I had not been confronted with before.

The person who might have been called my teacher would surely have wanted me to learn these lessons in an entirely different way, if I had to learn them at all, but there was no time beforehand, and not a moment left over at the end, to express any regret.

***

There was no Hebrew spoken during my bar mitzvah, nor did I read out aloud a portion of the consecrated biblical text. Everything happened in one language, or possibly two, but Hebrew was neither of them. I already knew a number of Hebrew words, for example those that mean good morning and good night, peace, excuse me, please and thank you, boy and girl, water and prickly pear. I also knew that ‘baruch’ meant blessed, and that ‘yael’ meant ibex, which is a kind of goat. Those were the names of my parents, Baruch and Yael. I was the fruit of the union between a blessed one and a wild mountain goat, the first of their three children, the eldest by seven and a half years, and also the eldest grandchild on both sides.

As might be expected, ‘baruch’ is a holy word; it is also the beginning of many prayers. ‘Baruch ata Adonai’, Blessed art thou, Lord. I would have appreciated just a touch of holiness to add to proceedings during the thirty-minute ceremony, and why not even a prayer.

Someone might have raised a ladder of luminous words mounting rung by rung beyond the narrow, low-roofed confines where the occasion took place. This proved to be not only impossible but entirely unthinkable.

***

Several of my companions had already started learning Hebrew in preparation for their bar mitzvahs at the age of eleven or even earlier. On afternoons after school they disappeared behind the door of a room adjoining the newly built local orthodox shul, which stood like a sentinel among blocks of flats and scattered trees not three minutes from the school soccer field.

I watched them emerging an hour or so later as if they had been forcibly held under water, spluttering Hebrew syllables and exchanging jibes about their teacher, who was apparently no more than a doddering old clown.

Bevakakaka. Ani rotze, ani rotze, ani rotten tomatoes.

Bonded together in mockery they hopped around on the grass of the soccer field, the sound of their laughter rippling upwards like a single shared flag of belonging above their heads. Though they might have needed to exorcise from their bodies the boredom of their lessons, there was no question of their wanting to escape the ultimate goal: they would all end up having a bar mitzvah in shul one Saturday morning or another in the foreseeable future.

They would walk down the carpet with the eyes of the men and boys, as also the women and girls in the upper gallery, upon them. They would approach the raised lectern, passing row upon row of men wearing yarmulkes and draped in talliths, then stand at the sacred scroll and read from it to the congregation before being showered with gifts and adoration and going on to have a feast and make a speech in a marquee.

Such a procession of Jewishness they brought together before me, those boys: Stanley and JP, who was an orphan and once had ringworm; Colin who (accidentally, with a cricket ball) broke my front tooth; Jonny with the swimming pool at the bottom of his garden where Doris Day had dipped her shapely body one fabled afternoon.

There was Derek with his smooth raven-black hair and his violin; freckle-faced David; Peter of the hospitable mansion with a boxing bag swinging in the middle of the garden and a great cage of singing birds to one side; Boykie and his inexhaustible supply of jokes; Malcolm, Stephen, Ashley, Jacky whose house had recently been burgled; slothful, scheming Paul of the slack belly and bank-bags bloated with marbles. Whatever has became of those boys, I wonder, every one of them from the plush and luxuriant, tree-lined northern suburbs of Johannesburg in the early 1960s?

Then again, was I not from the same suburbs, and Jewish too? What was so different about my family? Well, we did live in the most ramshackle house on our block, with earthquake cracks across the inside walls, goose-pimpled plaster on the outside. And, unlike any of my friends’ houses, ours was filled with almost nothing new.

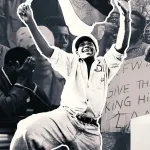

As of the age of eight or nine I was out with my father, weekend after weekend, scouting for furniture in other people’s homes: their inhabitants had fled the country in the wake of the Sharpeville massacre, the ensuing marches and violent repression of 1960. Added to this were the widely, luridly reported doings of the Mau Mau in Kenya. The writing is on the wall for the whites, went the rumour, and South Africa’s airports and harbours were a hive of activity that year as, with anxious alacrity, white families packed up and left.

We, of course, were never going to leave. Not ever. My friends’ parents might talk of buying a one-way ticket for London or Melbourne or New York, but not mine. And anyway we had just moved into our new antiquated house. So on a Saturday afternoon my father and I would add ourselves to a little crowd following a well-fed auctioneer about from room to stripped room of what had once been an absent stranger’s stately abode. After a few hours we drove back home to proudly lay our loot before my mother: Kilim carpets, a pinewood Swedish desk, lamps, vases, kitchenware, imbuia armchairs, a Morris settee dotted with little maroon roses.

At first the effect of all these things, once installed, was somewhat theatrical, like a stage set for what really stole the limelight in our house: books. I knew no one else whose house was filled with as many books, pushing their way up from the pinewood floors to the moulded ceilings; books with my parents’ first names inscribed inside them, looped together and underlined in my father’s meticulous script, Baruch & Yael, as if this were both their joint fortune and the contract of their togetherness.

Our garden, too, was different. The grass was as worn as a moth-eaten cloth, the flowerbeds lacking in that lush, perky look that comes with constant care. We had a gardener, but he was absent for weeks on end, a withdrawn, soft-spoken man who may well have been involved in some kind of political activity. On several occasions I saw my father speaking to him quietly around the back of the house; perhaps he was eventually arrested. Whatever the case, he finally disappeared, after which the grass was gradually worn even thinner than before.

But never mind the state of the grass, or the surfeit of books, or our adopted furniture. We were from the same suburbs as all my friends even if it felt as if we weren’t.

And what about the fact of being Jewish?

That was a secret which I myself could not crack. DM/ ML

My Thirty Minute Bar Mitzvah by Denis Hirson is published by Jacana Media (R260). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Comments - Please login in order to comment.