OBSTRUCTED WATER FLOW

River roadblocks — South Africa’s waterways need help to be brought back to life

Stained and depleted by the time they reach the coast, many rivers are in trouble. It’s not just sewage, plastic or industrial pollution. A multitude of man-made ‘roadblocks’ are restricting or completely stopping fish and other freshwater life from moving freely to breed and survive.

Far from being rivers of life, many of South Africa’s freshwater systems are becoming rivers of death – mere channels from which water is extracted, or used as a dumping ground for human and industrial effluent.

The problems of excessive water extraction and pollution of local rivers are relatively well known.

But there is another critical threat to river life that has received far less attention: the steady proliferation of man-made obstacles such as dams, weirs, culverts or river crossings that create physical barriers to the vital movements of fish and other aquatic life.

Much like birds and several animals, fish also need to move or migrate for a variety of reasons.

During the cold winter months, some species need to move into deeper, warmer water to survive sudden temperature shocks. When oxygen levels in the water drop suddenly because of rotting effluent, or when chemicals pollute their living environment, fish need an escape route to cleaner water.

And critically, many local fish species also need to migrate within a river system or into the sea (or vice versa) to complete their complex biological life cycles.

Several species live entirely within freshwater, but many others depend partly or entirely on the ocean to complete their life cycles.

Catadromous fishes (like freshwater eels) are born in the ocean, but they feed and grow in fresh waters or estuaries before returning to the sea many years later to breed.

The life cycle of several fish species such as the river bream depend on access to both fresh water and sea water. (Photo: Matthew Burnett/UKZN)

Towering concrete barrier traps

Now, however, many of these fish are increasingly trapped by a multitude of towering concrete barriers that have confined them into degraded living spaces that become inexorably smaller each year.

Dr Gordon O’Brien, an aquatic ecologist and senior lecturer at the University of Mpumalanga, reports that there are now more than 4,000 formal dams with impoundments and another 1,400 gauging weirs spread across rivers nationwide that form “partial, temporary or complete barriers to fish migration”.

Yet, there are only about 60 engineered fish-passageways across the country, and it remains unclear how well these structures are working.

This comes at a time when new dams or weirs are being planned on several of the last, largely free-flowing rivers in South Africa to store more water, including the Limpopo, Crocodile, Thukela, Umkomaas, Mzimkulu and Mzimvubu. None of these new structures will be legally obliged to incorporate fish pass structures.

Is there a solution to these problems?

“Yes,” suggests Dr Matthew Burnett, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) School of Life Sciences and senior scientist with the “Rivers of Life” aquatic health research group in Pietermaritzburg.

He is also closely involved in using fish telemetry to monitor the effectiveness of fishways and fish ladders – specially designed structures that have been fitted to several dams and other riverine obstacles across the world to give fish a fighting chance at migration or movement along obstructed river courses.

Earlier this month, at The Conservation Symposium 2022 in Scottburgh, Burnett chaired a special session on the numerous threats to local freshwater ecosystems entitled “Out of Sight, Out of Mind: The Fish Below the Surface”.

The session featured presentations by several aquatic researchers on the restrictions to movement in freshwater ecosystems in south and east Africa.

One such project, involving UKZN masters student Bradley van Zyl, is focused on the Lower Thukela Bulk Water Supply Scheme, which incorporates a 9m high concrete weir about 20km upstream of the Thukela River mouth. It’s the largest river in KZN and the second largest in the country.

Burnett notes that while the Lower Thukela weir incorporates an artificial fishway and rock ramp, it is still not clear whether these structures are working effectively to enable the movement of fish, and other aquatic life such as freshwater prawns or swimming (varuna) crabs.

In some senses, finding the entrance to the Thukela fishway is a bit like looking for a needle in a haystack, considering that the entrance is just 1m wide, whereas the weir is 100m wide. There is also a rock ramp that provides another 2m of width for fish movement.

Dr Matthew Burnett with a KZN yellowfish caught in the Dusi River near Pietermaritzburg. (Photo: Matthew Burnett/UKZN)

“One of the questions we are looking at is whether existing fishways or fishway design in South Africa can be improved for different local species, as most of these designs are adapted from salmon passages in Europe and North America,” Burnett told Our Burning Planet.

“What we are finding is that it’s hard to distinguish whether the fishway on the Thukela is working, or whether the abundance of fish is low because of multiple stressors, including effluent discharges from the Sappi pulp mill or the Mandeni industrial area.”

In other words, is poor passage design responsible for the low numbers of river creatures using the fishway and rock ramp? Or is pollution and reduced water flow driving down fish numbers in the lower reaches of the Thukela?

Van Zyl notes that up to 55Ml of water is abstracted daily from the Lower Thukela weir and there are plans to double this abstraction volume to 110Ml.

In such conditions, where fish abundance already seems to be declining, it is essential to ensure a guaranteed level of water for the environmental health of river life and for the dilution of industrial and domestic effluent.

On paper, the National Water Act makes provision for a minimum guaranteed water flow or “ecological reserve” to ensure the wellbeing of freshwater and the marine environment – but it remains unclear whether this reserve determination is implemented and enforced for all rivers.

“Getting the balance right between people’s needs and the environment’s needs will be challenging,” he says, noting that the Thukela is a perennial river whose mouth should remain open year-round – yet it was closed for two months last year.

“Its closure is almost unheard of, but sadly becoming a reality.”

Researchers Bradley van Zyl and Nolwazi Ngcobo with a marmorata eel caught in the Bushmens River, KZN. (Photo: Matthew Burnett /UKZN)

Freshwater eels

Over recent years, UKZN researchers have also been studying several life forms along the river – including the remarkable sea-to-river and river-to-sea movements of four freshwater (anguillid) eel species.

“Most people don’t realise that eels can move up to 2,000km to complete their life cycles – and some of these eels move all the way up to the Thukela Falls in the Drakensberg mountain range. We have caught some monster-size eels in the Thukela,” he said.

Several of these eels are already in trouble, according to recent studies by former UKZN researcher Dr Céline Hanzen.

In a research paper published earlier this year, Hanzen and her colleagues noted that the range of four freshwater eel species found in KZN rivers has declined by between 35% and 82% since the 1950s. She also warned that two of these species may be extirpated from the country in coming decades.

This is despite the fact that eels are remarkable climbers, with records of an African mottled eel being found 320km inland. During the 1960s, some eel species (such as the African longfin eel) were recorded at 1,670m above sea level in the Mzimkhulu River and in the Ncandu River, about 500km from the sea in the Thukela catchment.

Freshwater eels are not the only species in trouble.

Burnett is also worried about the red-tailed barb, a small fish species once common in KZN rivers but now classified as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Study of fish life

There is similar concern around the future of the indigenous yellowfish species in several local rivers.

This is one of the reasons why UKZN masters student Nolwazi Ngcobo is studying obstacles along the Msunduzi (Dusi) River system near Pietermaritzburg.

Ngcobo’s study of fish life in the Dusi is focused on the extent to which artificial barriers such as bridges and culverts (along with accumulations of plastic and other solid waste) prevent or restrict migration by fish and other freshwater species at six sites along this river system.

Burnett explained that the Camps Drift paddler ramp incorporates a fishway, but it’s still unclear how effective it is to facilitate fish movement.

The Dusi has also been in the news over recent years because of regular sewage spills from the Darvill wastewater treatment works and a devastating spill of vegetable oil and caustic soda from the Willowton Oil factory in August 2019. Fish, crabs and invertebrate life were all but wiped out from a 40km river stretch.

______________________________

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

______________________________

Burnett says that regardless of whether water quality improves or deteriorates in the coming years, fish will still need to move.

“When there are high levels of pollution, fish cannot escape or recolonise impacted areas – because they cannot move.”

In a paper published last year, Burnett and colleagues studied movements of KZN yellowfish along the Umgeni River between Midmar and Albert Falls Dams, and found that these fish deliberately seek out deeper, warmer river habitats when winter temperatures drop below a certain threshold.

Yet in the summer months, they also need to move up or downstream in search of food or unique spots to spawn.

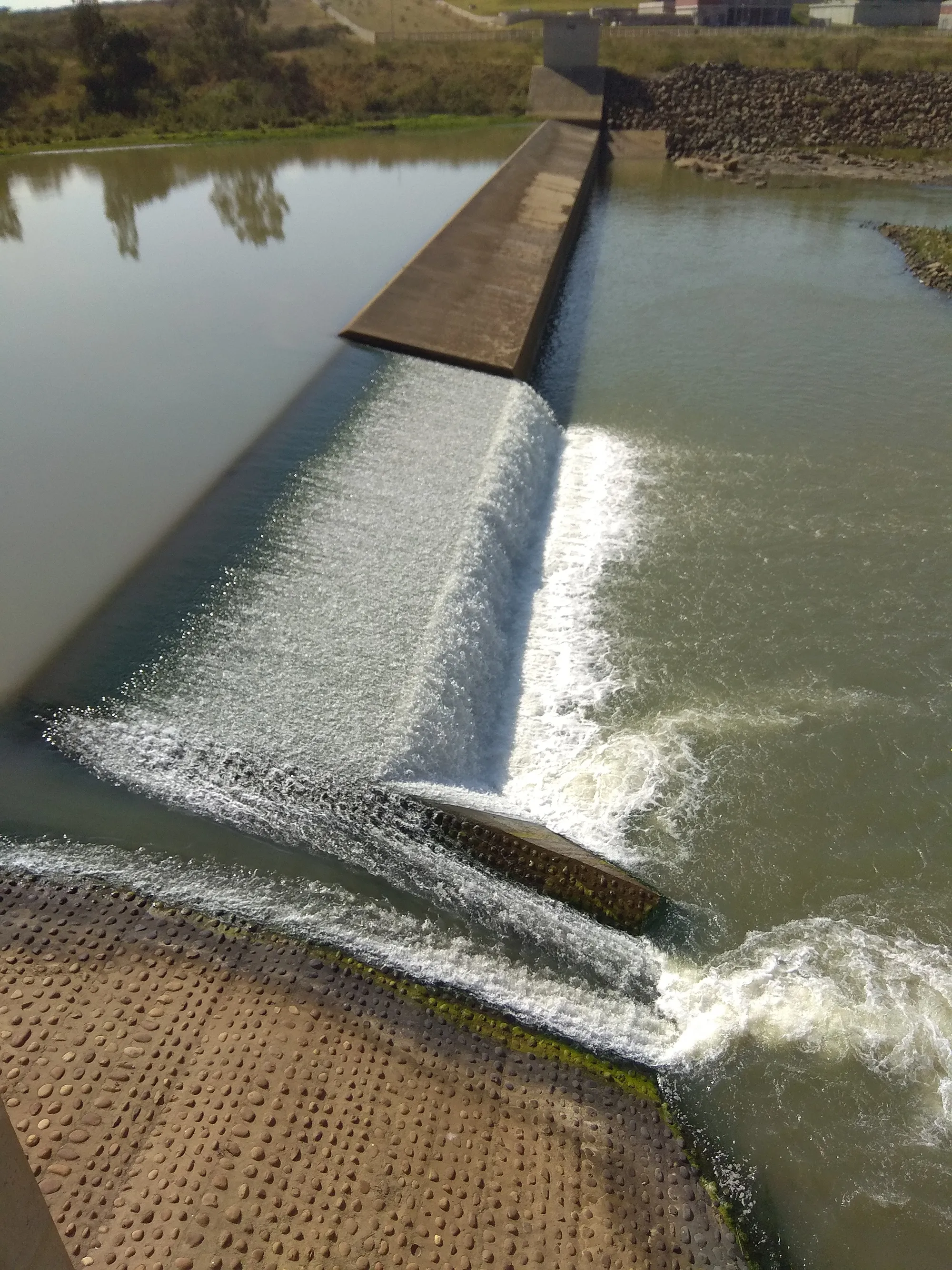

This sloping rockway on the Lower Tugela River weir was designed to help fish, crabs and other freshwater species to move upstream. (Photo: Bradley van Zyl/UKZN)

Removing river obstacles

According to Burnett, this growing global appreciation of the needs of fish gave rise to organisations such as the World Fish Migration Foundation, which is trying to remove river obstacles across the world.

So why aren’t there more fishways or fish ladders in South Africa’s rivers? And are there ways to design better road crossings, culverts and other river obstacles?

“We are often told that it costs too much. But one of the questions we need to be asking is: What barriers are there that don’t need to be there anymore? And what are the long-term costs for fish and the people who depend on fish?” Burnett asks.

Along the Dusi/Umgeni River system, there are currently no fishways or ladders on most of the constructed dams such as Inanda, Midmar, Albert Falls, Nagle or Henley.

While it seems highly unlikely that any of these dams will ever be demolished to restore fish migration paths, Burnett says there are some easy fixes available to retrofit fish ladders to some dams, or to replace smaller obstacles through better design.

One of the aims of Ngcobo’s study is to quantify the number and location of barriers in the Dusi, and also to examine whether it is possible to upgrade road crossings to cater for fish migration.

Burnett and his colleagues also point to the emerging risks that have become apparent on dry land, where wild animals isolated in relatively small game and nature reserves can suffer from genetic inbreeding depression because they can no longer migrate to ensure richer and more varied gene flows.

The same risks apply to fish. Over the long term – unless fish can move – their genetic richness and ultimate survival in several rivers remains in question, he warns. DM/OBP.

- Learn more about fish migration and barriers to their movement in this 35-minute World Fish Migration Foundation documentary.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.