SCOFF

Tallow: The fatty flavour foundation of Mzansi food

Without traditional fats, cooks cannot convey South Africa’s ancestral tastes and textures.

What would Italian food be without olive oil? Is French food even French without duck fat? These and many other regionally specific oils do so much more than fry. They not only carry and concentrate the tastes and aromas of other ingredients but also add unique, layered umami elements. Take away the oil that has evolved to grease the wheels of a culinary culture and that cuisine is robbed of its flavour foundation.

Which is why it is alarming that our nation’s heritage fats are almost entirely absent from modern South African cooking. Read historical cookbooks and anthropological accounts of various sorts of South Africans food and it becomes apparent that most of our classic recipes were intended to be made with one of two fabulous fats. For the northern regions that fat is marula nut oil. In the Cape, Free State and KZN it is sheep tallow.

When did you last see either in a supermarket? Savvy consumers can buy both but not without considerable effort. Which means that those trying to promote traditional tastes are almost always cooking with one hand tied behind their backs.

Because both fats would constitute too much good living for one article, I am temporarily parking marula nut oil which I will come back to in a subsequent story. For now, let us look at rendered (melted and clarified) sheep tallow. Specifically fat tailed, indigenous sheep tallow. As the name suggests, these creatures concentrate almost all body fat in their tails. In some cases, the extremity constitutes as much as 15% of the total weight of the animal. Occasionally farmers make them little carts to carry their appendages around.

Lamb tallow at Indochine restaurant. (Photo: Lizelle Lazarus)

For the sheep, this extra junk in the trunk is an evolutionary adaptation providing energy reserves in harsh, dry climates. For humans, the appeal is epicurean. All sheep have body fat that can be rendered and it all tastes good, but nothing tastes and feels quite as succulently silken as tallow extracted from fat tailed sheep. Since tail fat is exposed to cold more often than fat from other parts of the body, it has a lower melting point which contributes to a superb, soft, buttery mouthfeel. We are talking chocolate level melt-in-the-mouth magnificence. Did I mention the high smoke point? Real, old-school Namaqualand skuinskoek (aniseed infused fritters) made with and then fried in tallow are exquisite.

Sadly, these local bleaters are now few and far between having fallen out of favour and been largely replaced by imported animals in the 19th century. They are slow growing and small with hair, not wool. They are also reputed to be feisty. I can neither confirm nor deny this last trait as my experience has been mixed. I was once charged by a Namaqua heritage sheep at the Solms Delta estate, Franschhoek – in her defence, she did have a newborn with her, and I was walking towards the wine farm restaurant which served lamb fynvleis on a brioche-like tallow enriched bun. Conversely, I have never had anything other than serene sweetness from the Zulu Swelamadlebe (literally those lacking ears) sheep at Enaleni Farm (35km from Hillcrest, outside Durban).

While fat doesn’t fossilise, rock art depicts unmistakably fat tailed sheep and the earliest written records are replete with reference to their tasty tallow. From 1849 to 1853 Francis Fleming served at King William’s Town as chaplain to the British troops. In his book, Kaffraria and its inhabitants (1853), Fleming writes that: “Both Korannas and Bushmen live for months on locusts which they grind into a meal, mix with sheep fat and bake into breads.” I was recently served a slice of mopane flour bread at a Cape Town hipster popup. After one bite my mouth was sandpaper dry. Having read Fleming’s description I think I know what the chef did wrong. Experienced insectivors know to include tallow in the dough.

Where there is bread there is spread. Renata Coetzee’s book A Feast from Nature: Food Culture of the First Humans on the Planet (2015) offers us recipes for Khoi breads (some made with flour obtained from indigenous dried and ground veld plants and other transitional culture wheat flour doughs) which were “spread with rendered lamb fat which was considered a special treat when served with a syrup prepared from suikerkan (sugar bush protea nectar)”.

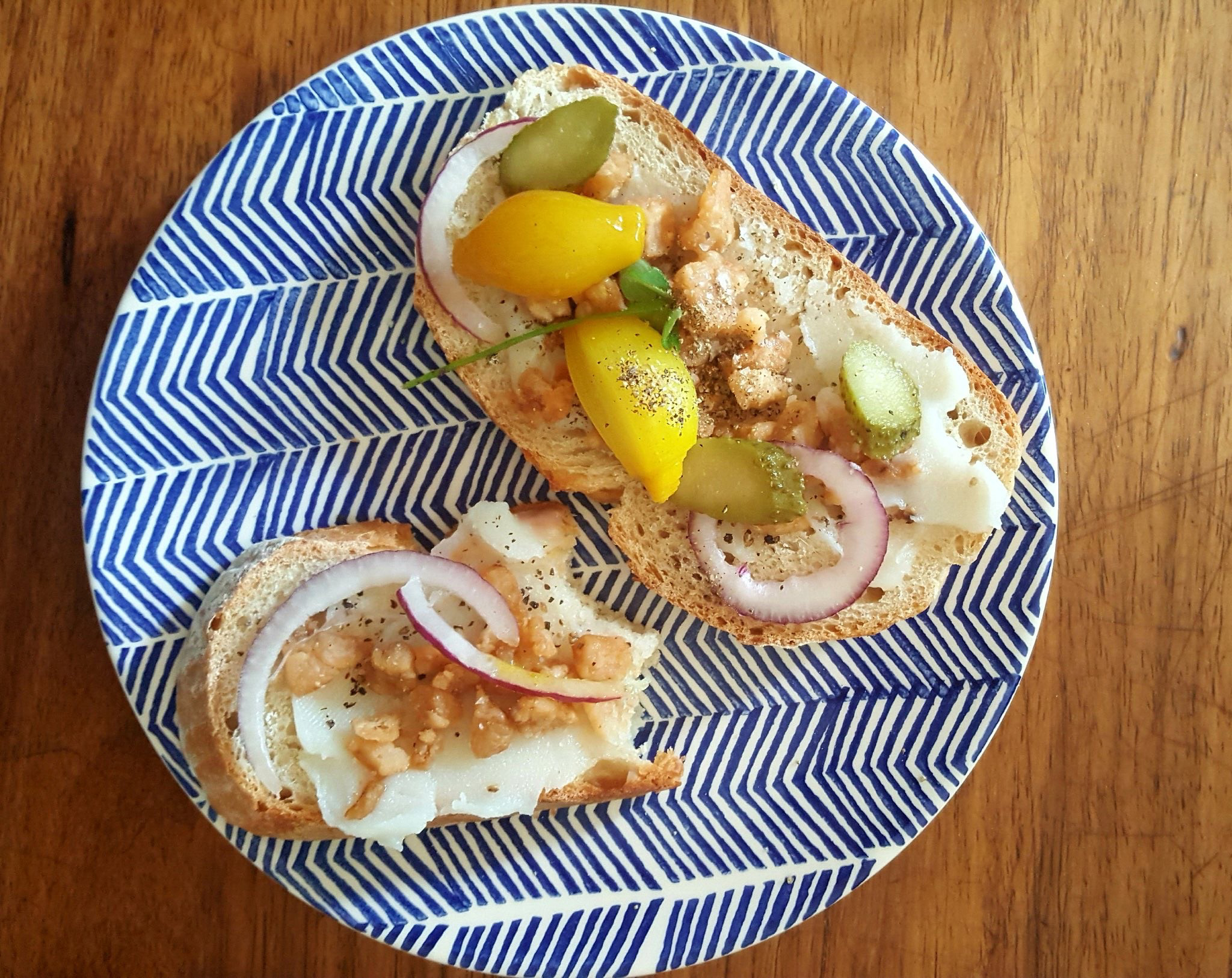

Vestiges of significant cross-cultural fusion at the Cape are apparent in food writer Errieda du Toit’s memory of: “My mother’s favourite treat of soft, white skaapvet with golden syrup on soetsuurdeeg bread. Mixing golden syrup (or further back – wild honey) with the fat is called ‘rekvet’ (‘stretched fat’) as mixing the runny syrup – a luxury – with the fat, prevents the syrup from dripping down the bread and wasting the precious sweet.” For those of a more savoury disposition Errieda’s skaapvet sandwich with curried pickling onion salad is a foretaste of heaven.

Errieda du Toit’s sandwich with tallow kaiings and curried pickling onion salad. (Photo: Ian du Toit)

In the Eastern Cape chef Siya Kobo has childhood memories of: “My mother always finishing the cooking of her wonderful umngqusho with a spoon of tallow. Almost in the same way that Italians might add parmesan cheese at the end of making risotto. It was that lamb fat that turned a relatively plain starch into something more than that. Savoury, meaty, almost gamey. It brought out the soft sweetness of maize and earthy, nuttiness in beans. Something that could have been flat became three dimensional, precisely because the fat was carrying the flavours.“ Chef Kobo also recalls imbicane (pigweed, wild herb) fried in such fats.

Beyond the pleasures of rendered fat is the bliss of its byproduct. As the fat is melted down, there are golden brown crispy bits that will not render. This deeply delicious, unmeltable sediment, once sieved and set aside, is variously known as kaiings (Afrikaans), greaves (English), amankanya (isiXhosa).

Surita Riffel has this memory of her Franschhoek childhood: “My ouma het ’n spesiale pot gehad waarin sy kaiings uitgebraai het. Dit in ’n Consol fles vir paar daê in yskas gehou en daarmee vir ons die heerlikste kaiing bakbrood gemaak. Die spierwit vet was ook so gebêre in die yskas. Glaspotjies met skroefdeksels. En dit was later gebruik om kos mee te maak ipv [in plek van] olie, veral bredies soos kool, groenboontjie en wortelbredie. Die vet was ook gedeel met mense wat kom vra het vir dit. Om kos te deel was vir haar niks. Vandag is dit ingeprent in my. Ek deel graag kos uit. Brood veral, iets lekker wat ek soms in oormaat maak. Ek moet deel en dis lekker… Ons het as kinders voor my ouma se kolestoof gesit en kaiings eet.. wat sy spesiaal vir ons uitgehou het. Heerlik sout. Ek dink nou met heimee terug na my ouma se warm kaiingbrood.”

Translated: “My grandmother had a special pot in which she fried kaiings. Kept it in a consol jar in the fridge for a few days and made us the most delicious kaiing baked bread. The pure white fat was also stored like this in the fridge. Glass jars with screw lids. And it was later used to make food instead of oil, especially stews such as cabbage, green bean and carrot bredie. The fat was also shared with people who came to ask for it. Sharing food was nothing to her. Today it is imprinted in me. I like to share food. Bread especially, something delicious that I sometimes make in excess… As children we sat in front of my grandmother’s coal stove and ate kaiings… which she kept especially for us. Deliciously salty. I now think back to my grandmother’s warm kaiing bread.”

My reading of Ouma Riffel’s method is that she put the crackling on top of the bread whereas Vissie Oberholster in Upington puts kaiings into her soetsuurdeegbrood dough. I suffer from intense ouma envy when I read about the late great chef and food writer Niël Stemmet’s Robertson grandmother who made kaiing soetkoekies. The recipe for which is in his wonderful memoir/ recipe book Salt+pepper: Heritage Food/journey.

And let us not leave the Riffel household without underlining the importance of that bredie. A Cape lamb tail stew with waterblommetjies bobbing about is a glorious Khoi-Dutch creole creation. Especially when finished with a sprinkling of suring to create crisp, tart contrast against the opulent tallow-led lamb.

So, what happened? Essentially everything you currently cook with either butter or sunflower/olive oil was once made with sheep fat. One minute we were all juice and joy and the next we were stuck in a tranche of trans-fats. I have already explained the relative absence of fat tailed sheep tallow but even their thin tailed cousins potentially produce deeply delicious rendered oils.

So, where is it and why aren’t we using it? For some South Africans it was land dispossession, apartheid geography and poverty that limited access to sheep. For others it was (now mostly debunked) dire warnings about the link between saturated animal fats and heart health that caused those jars of tallow to all but disappear from Mzansi’s modern kitchens. With the tallow went much of the taste and texture that once carried South African cuisine. It is possible to make bredies, umngqusho, wild leaf melanges and all manner of doughs without tallow but it’s nowhere near as nice. By the same token I could try to make a lamb curry without ghee, chow mein without sesame oil and pasta alla Genovese without olive oil – but why would I?

All of the above explains why I was so ridiculously happy on my recent visit to Indochine restaurant on the Delaire Graff Estate, Stellenbosch. Chef Virgil Kahn’s bread basket included delicious dombolo-style steamed buns and a kaiing-topped quenelle of lovely lamb fat. Obviously, I enjoyed the entire meal, but it is the tallow and kaiings that I regularly return to in my dreams…. DM/TGIFood

The author supports the Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and Children in Manenberg.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.