THE CONVERSATION

Scientists calculate the risk of someone being killed by space junk

The southern hemisphere is more likely to be hit by space debris than the northern one.

The chance of someone being killed by space junk falling from the sky may seem ridiculously tiny. After all, nobody has yet died from such an accident, though there have been instances of injury and damage to property. But given that we are launching an increasing number of satellites, rockets and probes into space, do we need to start taking the risk more seriously?

A new study, published in Nature Astronomy, has estimated the chance of causalities from falling rocket parts over the next ten years.

Every minute of every day, debris rains down on us from space – a hazard we are almost completely unaware of. The microscopic particles from asteroids and comets patter down through the atmosphere to settle unnoticed on the Earth’s surface – adding up to around 40,000 tonnes of dust each year.

While this is not a problem for us, such debris can do damage to spacecraft – as was recently reported for the James Webb space telescope. Occasionally, a larger sample arrives as a meteorite, and maybe once every 100 years or so, a body tens of metres across manages to drive through the atmosphere to excavate a crater.

And – fortunately very rarely – kilometre-sized objects can make it to the surface, causing death and destruction – as shown by the lack of dinosaurs roaming the Earth today. These are examples of natural space debris, the uncontrolled arrival of which is unpredictable and spread more or less evenly across the globe.

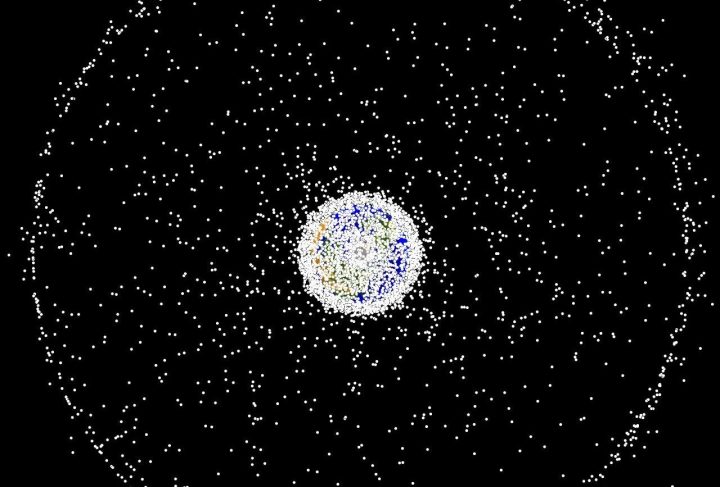

The new study, however, investigated the uncontrolled arrival of artificial space debris, such as spent rocket stages, associated with rocket launches and satellites. Using mathematical modelling of the inclinations and orbits of rocket parts in space and population density below them, as well as 30 years’ worth of past satellite data, the authors estimated where rocket debris and other pieces of space junk land when they fall back to Earth.

They found that there is a small, but significant, risk of parts re-entering in the coming decade. But this is more likely to happen over southern latitudes than northern ones. In fact, the study estimated that rocket bodies are approximately three times more likely to land at the latitudes of Jakarta in Indonesia, Dhaka in Bangladesh or Lagos in Nigeria than those of New York in the US, Beijing in China or Moscow in Russia.

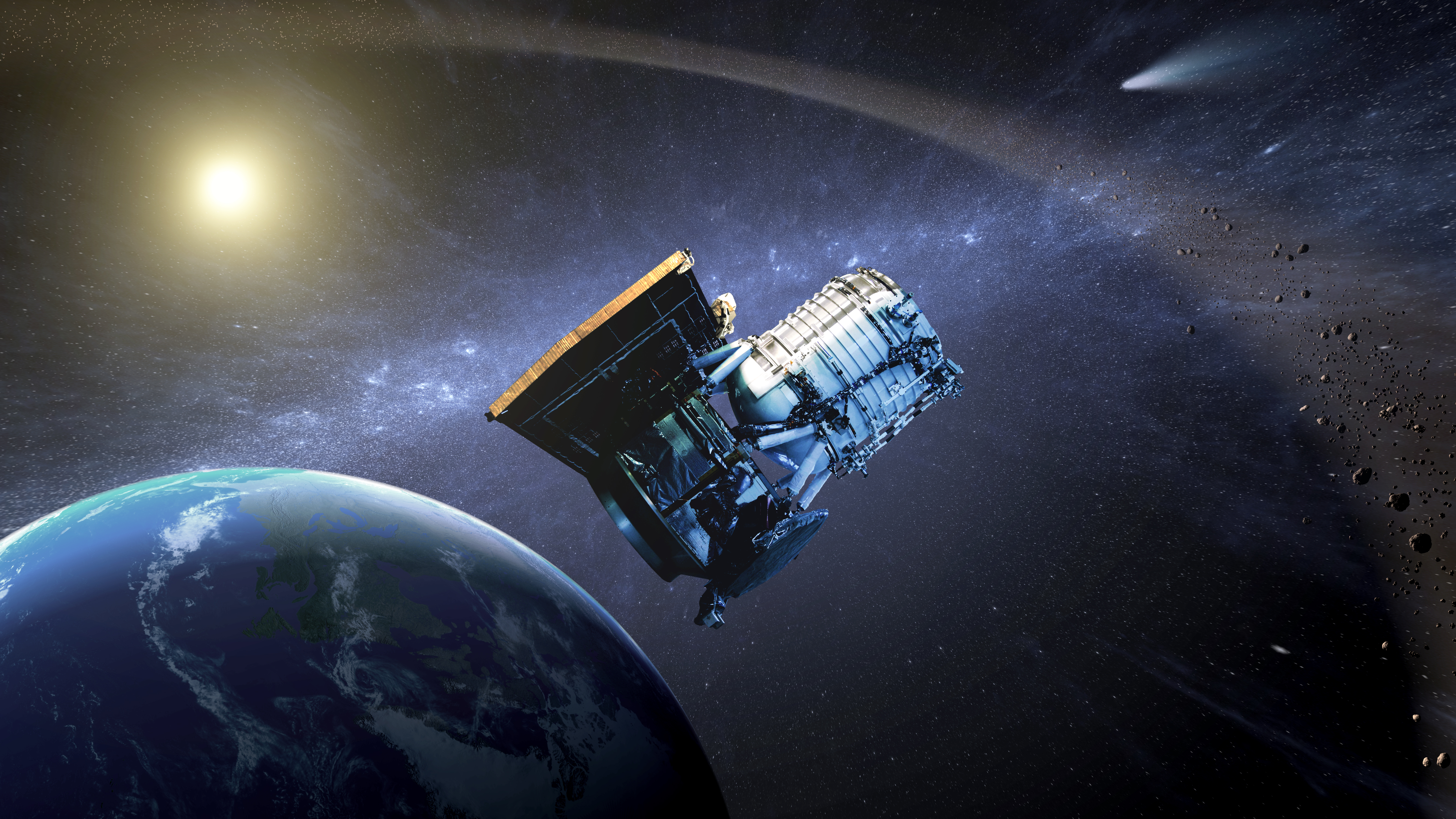

Artist’s concept of NASA’s WISE (Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer) spacecraft, which was an infrared-wavelength astronomical space telescope active from December 2009 to February 2011. In September 2013 the spacecraft was assigned a new mission as NEOWISE to help find near-Earth asteroids and comets. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

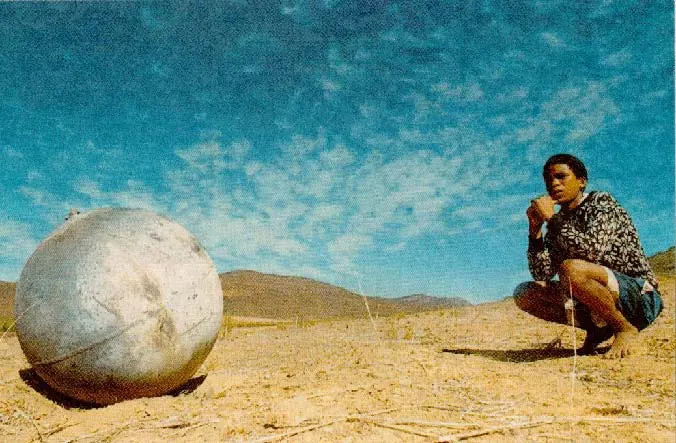

Theodore Solomons sits next to the metal ball that he saw fall from the sky on a farm close to Worcester, about 150 kilometres outside of Cape Town, South Africa in April 2000. A second metal ball dropped out of the sky the following day on a farm approximately 50 kilometres outside of Cape Town. Astronomers said the balls, which were white-hot when they landed, could be parts of a decaying satellite. Image: Enver Essop/EPA

The authors also calculated a “casualty expectation” — the risk to human life — over the next decade as a result of uncontrolled rocket re-entries. Assuming that each re-entry spreads lethal debris over an area of ten square metres, they found that there is a 10% chance of one or more casualties over the next decade, on average.

To date, the potential for debris from satellites and rockets to cause harm at the Earth’s surface (or in the atmosphere to air traffic) has been regarded as negligible. Most studies of such space debris have focused on the risk generated in orbit by defunct satellites which might obstruct the safe operation of functioning satellites. Unused fuel and batteries also lead to explosions in orbit which generate additional waste.

But as the number of entries into the rocket launch business increases – and moves from government to private enterprise – it is highly likely that the number of accidents, both in space and on Earth, such as that which followed the launch of the Chinese Long March 5b, will also increase. The new study warns that the 10% figure is therefore a conservative estimate.

What can be done

There are a range of technologies that make it entirely possible to control the re-entry of debris, but they are expensive to implement. For example, spacecraft can be “passivated”, whereby unused energy (such as fuel or batteries) is expended rather than stored once the lifetime of the spacecraft has ended.

The choice of orbit for a satellite can also reduce the chance of producing debris. A defunct satellite can be programmed to move into low Earth orbit, where it will burn up.

Farmer James Striton next to a metal object he discovered on his farm in Cheepie, 130km from Charleville in southwestern Queensland in November 2007. The ball of twisted metal is believed to be space junk, possibly from a rocket used to launch satellites into space. EPA/James Striton

The NASA Orbital Debris Program Office, recognized worldwide for its initiative in addressing orbital debris issues, determined that this large piece of debris was the main propellant tank of the second stage of a Delta II launch vehicle. Image: NASA

There are also attempts to launch re-usable rockets which, for example, SpaceX has demonstrated and Blue Origin is developing. These create a lot less debris, though there will be some from paint and metal shavings, as they return to Earth in a controlled way.

Many agencies do take the risks seriously. The European Space Agency is planning a mission to attempt the capture and removal of space debris with a four-armed robot. The UN, through its Office of Outer Space Affairs, issued a set of Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines in 2010, which was reinforced in 2018. However, as the authors behind the new study point out, these are guidelines, not international law, and do not give specifics as to how mitigation activities should be implemented or controlled.

The study argues that advancing technologies and more thoughtful mission design would reduce the rate of uncontrolled re-entry of spacecraft debris, decreasing the hazard risk across the globe. It states that “uncontrolled rocket body reentries constitute a collective action problem; solutions exist, but every launching state must adopt them.”

A requirement for governments to act together is not unprecedented, as shown by the agreement to ban ozone layer-destroying chlorofluorcarbon chemicals. But, rather sadly, this kind of action usually requires a major event with significant consequences for the northern hemisphere before action is taken. And changes to international protocols and conventions take time.

In five years, it will be 70 years since the launch of the first satellite into space. It would be a fitting celebration of that event if it could be marked by a strengthened and mandatory international treaty on space debris, ratified by all UN states. Ultimately, all nations would benefit from such an agreement. DM/ML

This story was first published in The Conversation.

Monica Grady is a Professor of Planetary and Space Sciences at The Open University.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.