Theatre Review

Kunene and the King: A meditation on power and the violence of racism

“The weight of this sad time we must obey. Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.” — Shakespeare, King Lear

On 16 June, after joining a long day’s march with young people to the Union Buildings, I went to watch John Kani and Michael Richard perform Kani’s play Kunene and the King at the Joburg Theatre.

I wasn’t disappointed. I was reminded why the theatre was such a wonderful invention. It has the power to induce reflection on the state we are in — be it personal or political — that is as strong today as it was after Shakespeare had the Globe Theatre constructed on the banks of the River Thames 423 years ago.

Kunene and the King was written by Kani to mark the 25th anniversary of our democracy. It was first produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company and performed in London’s West End to critical acclaim, interrupted by Covid and came home in 2022. It’s a meditation on racism and reconciliation in South Africa pre- and post-1994, a tale told through the experience of an ageing cancer-afflicted actor, Jack Morris and his male nurse, Lunga Kunene.

A tale told by an actor signifying everything.

Sounds like we’ve been through these themes before?

Maybe, but Kani does it differently. His is a tragi-comedy about two frustrated men looking back in anger. One has lived vicariously through Shakespeare’s tragic heroes, the other was a would-be doctor cum nurse. One is thwarted by alcoholism and his own mediocrity; the other by apartheid, racism and ironically the comrades.

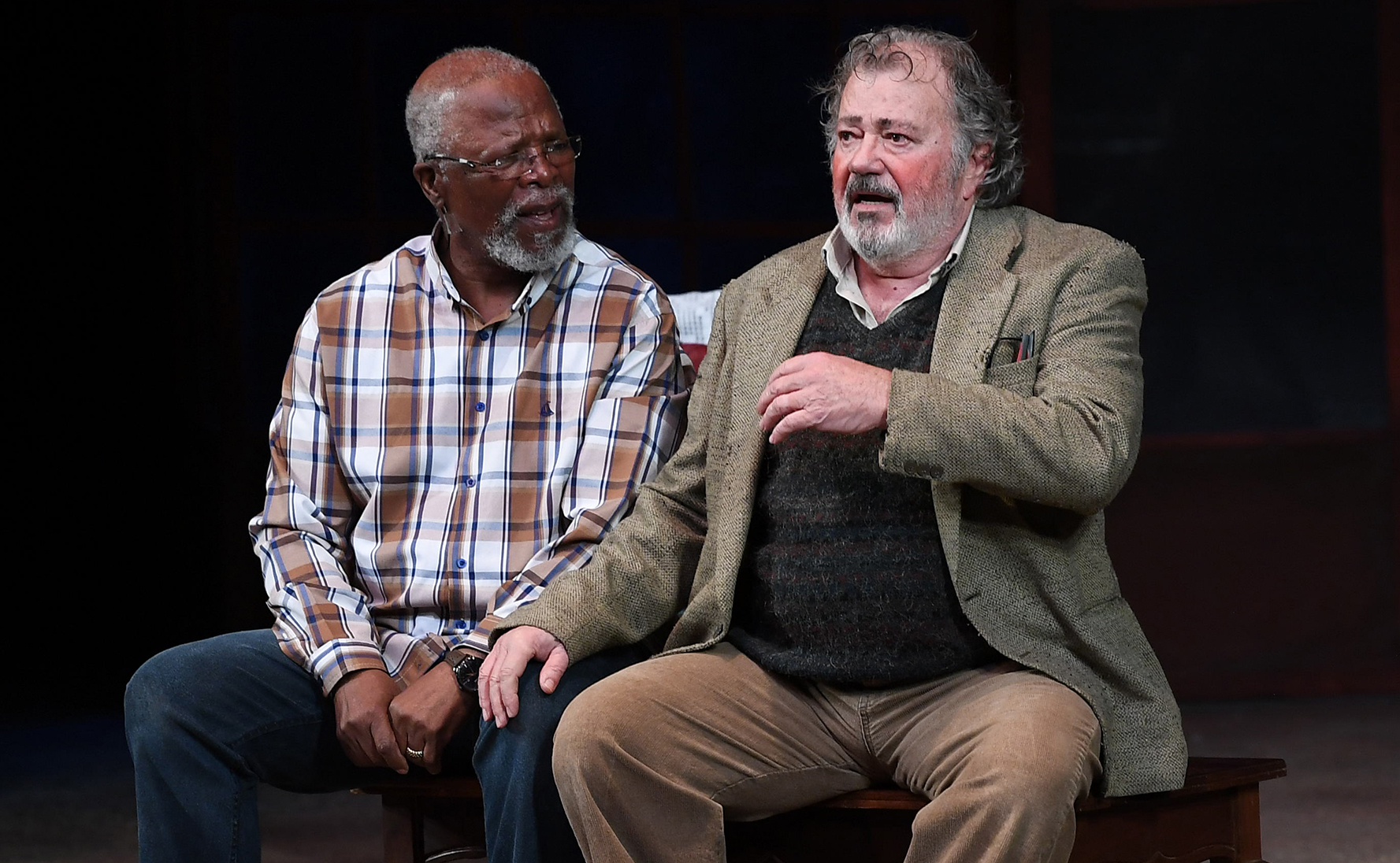

Michael Richard & Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

Michael Richard & Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Frennie Shivambu)

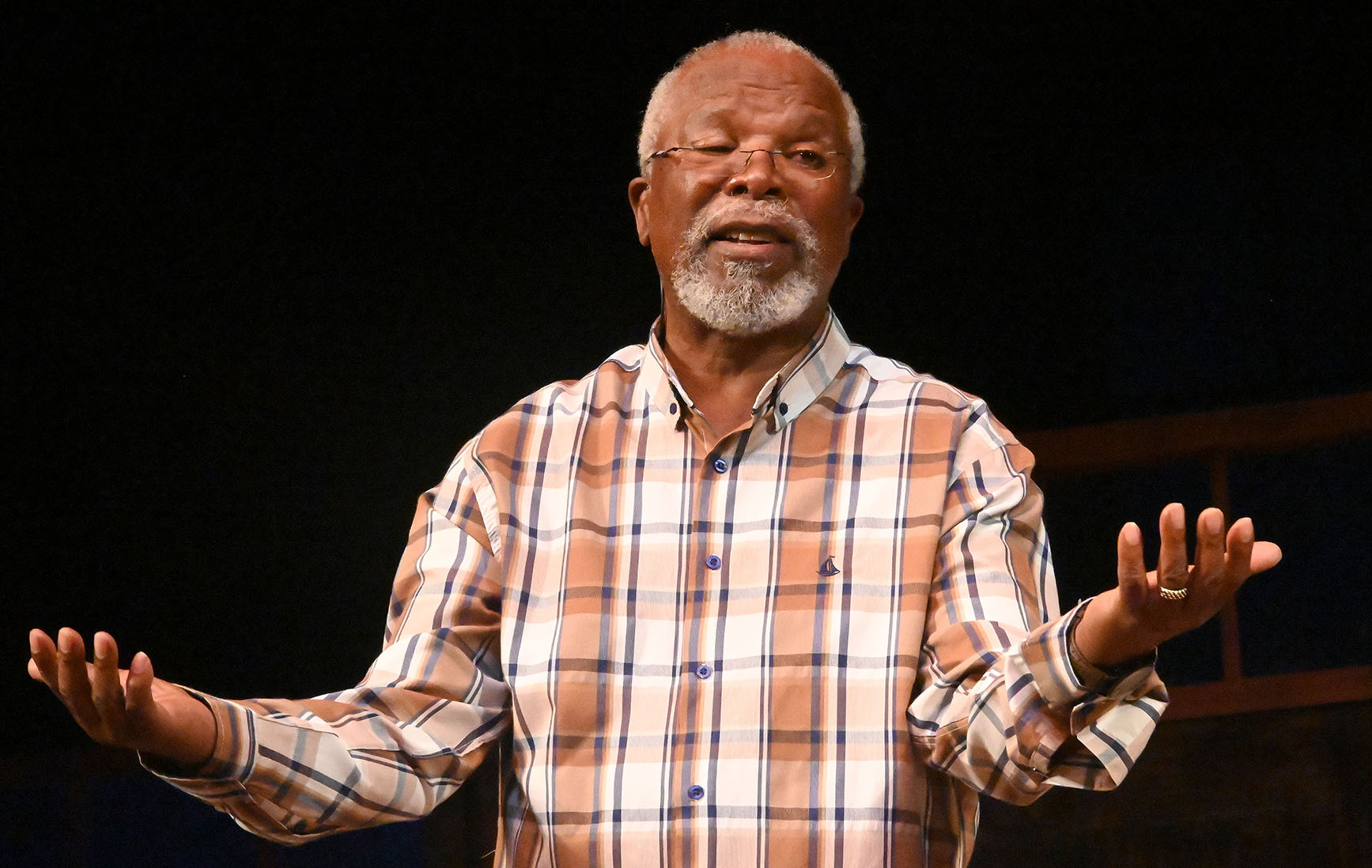

Michael Richard & Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Frennie Shivambu)

The duet takes place over three scenes, as Jack prepares haplessly and increasingly hopelessly for one last performance of King Lear that his cancer will not let happen. This way, snippets of Shakespeare’s plays, King Lear in particular, become the pivot for a reflection on racism, poverty and the souls of South African folk.

As Kunene and Morris clash with each other, sometimes humorously, sometimes violently, Jack comes to understand that the weeds of racism have long remained untended in his own backyard.

Or does he?

We might call Morris’s the ‘civilized racism of the suburbs’, the benign demeaning of black personhood that takes place behind high walls. It’s comic because it’s ridiculous (and Kani shows us why), but it’s also tragic.

Riffing with Shakespeare sets up some wonderful scenes. It bears out the fact that, counter-intuitively, Shakespeare has long been complicit with black South Africans’ struggles for liberation and revolution.

The Bard, represented in the play by a bust, had been brought to black South Africans through mission schools like Lovedale College, where (for the most part) his plays were taught to demonstrate the heights reached by Western civilisation. To intimidate, as it were.

Michael Richard & Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

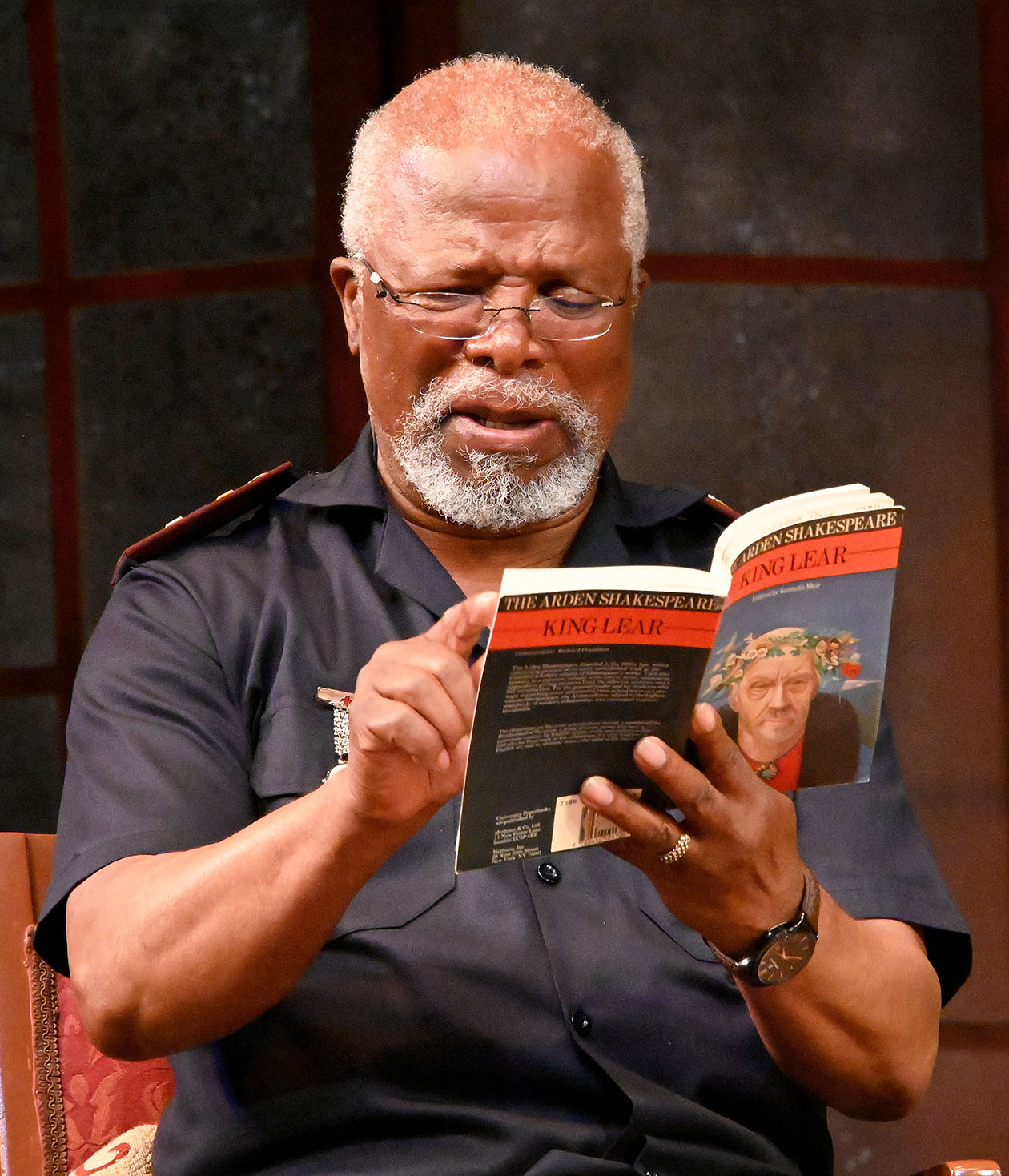

Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

But ironically black students instead found something deeper and more revolutionary in Shakespeare, for reasons Kani explains briefly in his introduction to the text of the play (published by Jonathan Ball in 2021). Sol Plaatje was a fan, so was AC Jordan, Mandela and Chris Hani.

The deep and nuanced relationship between Shakespeare and black South Africans, his re-appropriation from whiteness, makes a mockery of the superficiality of white people’s understanding of the Bard. For them Shakespeare is a bauble not a beacon; in reality he is a figure more sinned against in the way his plays have been appropriated by ruling classes, than sinning in the actual text of the plays (as some anti-colonialists would argue).

Kani makes fun of this.

For example, Lunga recalls how “under Bantu Education one Shakespeare was enough for a native child. What use will Shakespeare be in his later life under Apartheid? So said Dr Hendrik Verwoed.”

But, in the next breath, Kani has Lunga make a mockery of the fact that “a couple of years ago our government suggested that Shakespeare be dropped from the syllabus of all schools and be replaced by other African languages.”

The worst returns to laughter indeed.

The truth is that in much of African literature and liberation philosophy there is a demonstrable affinity with Shakespeare and multiple reasons for it.

There is the poetry the Bard extracts from the English language and its closeness to the natural rhythms, metaphors and expressiveness of African languages. In Kunene and the King this is captured in a wonderful scene where the two men discuss Julius Caesar, with Morris reciting Antony’s funeral speech (“for some reason, I’m into funerals these days”) and Kunene providing a simultaneous translation into Xhosa (as translated long ago by WB Mdledle).

Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The play was written by South African actor, activist and playwright John Kani and marks the 25th anniversary of the end of apartheid in South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

Michael Richard & Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

‘Shakespeare lives’ — John Kani

But there’s also a deadly serious side to the invocation of Shakespeare. Many of Shakespeare’s plays are a meditation on power, war and the irrepressible humanity of the poor, even when faced with the worst of material circumstances and the worst of oppression. So it’s perhaps not surprising that in Kunene and the King, the meaning of Lear’s “O, reason not the need” speech is recalled and debated between the two as Jack explains to Lunga why in his preparation he first has to translate Shakespeare into ‘English-English’.

The speech reflects Lear’s growing realisation that as King he has neglected the poor:

Jack: ‘O, Reason not the need’ … Don’t ask why people need things … ‘Our basest beggars are in the poorest things superfluous’ … Even a beggar owns something he doesn’t strictly need …

Lunga: And what does this king know about beggars?

Jack: Not much. Yet. He’ll have just seen them from his horse and carriage.

Lunga: Like here is Joburg, when you stop at the traffic lights.

In essence, the play uses Shakespeare as a prop to meditate upon South Africa’s past and present and the unstaunched wounds of micro-racism. On that 16 June night at the Joburg Theatre, the audience was overwhelmingly black. There was much nodding, nudging and exhaling as people recognised the everyday micro-racisms of Jack Morris.

Michael Richard & Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

Michael Richard & Dr John Kani at the Premiere of Kunene And The King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre on May 29, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

For white people in the audience, by contrast, the play must have been more difficult because the racism it depicts comes from the mouth and behaviours of a likeable and humorous “artiste” not a villain. What we are made to witness is not the boorish racism of the Boer but the everyday racism that still permeates most white households in language (“You people”), in not seeing black people, even those you work with (Jack Morris can’t remember his “maid’s” surname (“It starts with an ‘M’ like they all do. Thabo Mbeki. Mbuli, Mbata, Mbethe. Mum, mum, mum, mmmmmm.”) and in still not understanding the hurt and existential disruption that apartheid caused to all black people.

As a white person, it’s hard to other yourself from it.

That’s why the play’s climax and bathetic denouement is so powerful. Eventually, but only momentarily, Lunga loses his control and expresses all his hurt, this after proper Jack has told him he never voted for the Nats:

Jack: “Here we go again. Steve Biko, Chris Hani. Fucking Vlakplaas. The same old shit, it’s like a stuck record.”

Sounds familiar?

To which Lunga retorts:

“My life has been stuck. Stuck because of you.”

By the end, watching John Kani perform Kunene and the King on 16 June 2022 had unintentionally proved to be the best way to meditate on the meaning of 16 June, 1976 and the failures of our white selves and the ANC to seriously address racism and reconciliation. Kani puts it this way in his introduction: “Their relationship examines the very foundation on which our democracy is built.”

Before concluding: “Shakespeare lives!” DM/MC/ ML

Kunene and the King, a play by John Kani, published by Jonathan Ball (2021), is at the Playhouse Company until 3 July. On the day I sought it out from Exclusive Books, there were 353 copies available, but all in one store, the Mall of the South, and only one in one other shop in the country. What does that tell you?

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.