Maverick Life

Sol Plaatje and Shakespeare: A Lovedale love story

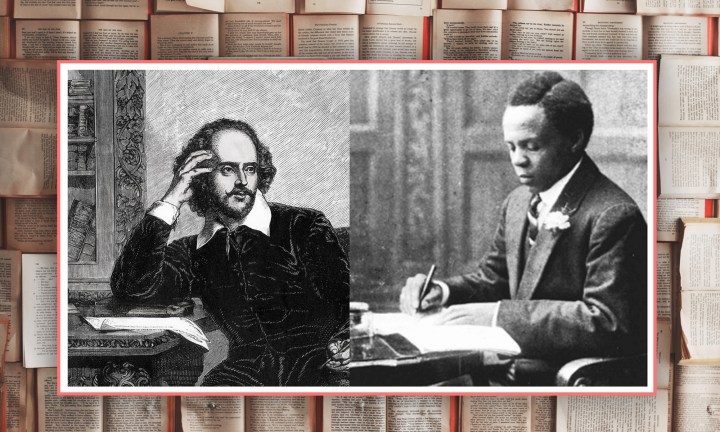

A 1995 research paper by Maverick Citizen Editor Mark Heywood reveals how a love affair between Sol Plaatje and Shakespeare left a deep impression on the writer’s own literary and intellectual views.

This is the strangers case;

And this your mountainish inhumanity.” – William Shakespeare, Sir Thomas More

“The viewpoint of the ruler is not always the viewpoint of the ruled.” – Sol Plaatje, Mhudi

Publishing houses are nothing without the stories they publish. It is what keeps the money flowing and, much like a doctor without patients, a publishing house without stories is redundant.

The 200-year old Lovedale Press has had an abundance of stories as books flow out from its hallowed doors, many being a first of something: a first Xhosa novella, a first black author publishing a novel, a first black dramatist, the firsts are endless. Lovedale, in Alice in the Eastern Cape, produced and published some of the most influential African intellectuals in the country.

Now threatened by closure, one of its most hallowed alumni, Sol Plaatje, and his love affair with Shakespeare is gaining new attention in a country grappling with Shakespeare’s role in our modern-day dialogue. Plaatje’s work, all published by Lovedale Press, is one of the multitude of Lovedale stories that warrants exploration.

His missionary school education sparked a love for language that would develop into a career of words in journalism and writing.

For many born-free South Africans, the name Sol Plaatje evokes images of a dusty university in suburban Kimberley or a woefully corrupt municipality, blissfully unaware of the immense influence he had on the rich tapestry of South African history. A group of Lovedale alumni, most notably Isaiah Bud-M’Belle, hosted literary evenings that prompted a love affair between Plaatje and Shakespeare that left a deep impression on his own literary and intellectual views.

Plaatje was one of South Africa’s foremost activist politicians, focused on the liberation of the African population. His crowning achievement, and what he is best remembered for, is the founding of the South African Native National Congress, of which he served as Secretary-General, and which a decade later would become the African National Congress.

His missionary school education sparked a love for language that would develop into a career of words in journalism and writing. He served as editor of local newspapers published in indigenous South African languages. Plaatje himself was fluent in several languages and would later go on to translate Shakespeare plays into Tswana.

Editor of Maverick Citizen Mark Heywood delved deeper into this subject in his master’s thesis, written in 1995 and dubbed “Lovedale, literature and cultural contestation” which, in one of the chapters, tracked the beginnings of Plaatje’s relationship with Shakespeare.

Plaatje became the first black South African to write an English novel, titled Mhudi, which tried to retell and reclaim the African story, focusing on the Transvaal Kingdom and the wars of that time. The story was told in a unique blend of African folktale and traditional Western novel techniques. This was in line with Plaatje’s own views, quoted in Heywood’s thesis which he expressed as “a common fund of literary and cultural symbols” that he believed the West and Africa could and did share.

Plaatje would later go on to write a book titled Native Life in South Africa. A formative book of political protest described by Njabulo Ndebele, the former Vice-Chancellor of UCT as “Plaatje’s investigative journeying into South Africa’s rural heartlands to report on the effects of the [1913 Natives Land] Act and his involvement in the deputation to the British imperial government. At the same time it tells the bigger story of the assault on black rights and opportunities in the newly consolidated Union of South Africa – and the resistance to it”.

Sol Plaatje never officially attended Lovedale, instead moving to Kimberley. It was, however, the alumni of Lovedale that introduced him to Shakespeare more holistically and it was the Lovedale Press which published his novel and translations.

“He was introduced to Shakespeare during his education at the Pniel mission by Mrs Westphal,” Heywood notes.

“His interest was aroused after he watched Hamlet performed in a Kimberley theatre in 1896. But he attributed most of his passion to his coming into contact with a circle of ex-Lovedalians and SANCs at Kimberley, notably Isaiah Bud-M’Belle. Shakespeare had by then become all the rage.

It was the first time an African writer had written a praise-piece about Shakespeare and it remains the most valuable insight into his thinking on the author.

“Plaatje and his friends saw no reasons why Shakespeare should not be as accessible to them as he was to their white fellow citizens. This group held literary evenings which were often spent reading and discussing Shakespeare’s plays. Commenting on the results of his reading, Plaatje noted how he had found that ‘many of the current quotations used by educated natives to embellish their speeches, which I had always taken for English proverbs, were culled from Shakespeare’s works’ ”, writes Heywood.

However, the love of Shakespeare was not restricted to Plaatje and his close circle. By the 1870s, Shakespeare had become immensely popular at Lovedale and this popularity scarcely waned in the following decades.

Heywood continues, “According to Dan Twala, a student at Lovedale in 1924, there was by then a feeling that ‘if you can’t say anything about Shakespeare then you don’t know English. Shakespeare was therefore used to embellish the speeches of African politicians; to urge forward the development of an African literature’ ”.

In 1916, Sol Plaatje penned his homage to Shakespeare entitled A South African Homage. It appeared in English and Setswana in the Book of Homage to Shakespeare, published by the much better funded Oxford University Press. It was the first time an African writer had written a praise-piece about Shakespeare and it remains the most valuable insight into his thinking on the author.

The Shakespearian influence on Plaatje is multifold. First and foremost, it influenced his own writing. In an essay, Stephan Gray, a South African academic and writer, argued that Plaatje mimicked Shakespearean writing, more than it mimicked the 19th century contemporary Western writing of Plaatje’s time. Shakespeare undoubtedly shaped the narrative of Plaatje’s writing, the extent to which only the author would fully know. Heywood summarised it as “traces of Shakespeare began occurring in texts as diverse as Mhudi”.

In Plaatje’s Preface to Mhudi, an explanation to why he wrote the novel is found; he puts forward two reasons, the first is, in his words, “to interpret to the reading public one phase of ‘the back of the Native mind.’ ” His second reason was to raise money “to collect and print Sechuana folk-tales, which with the spread of European ideas, are fast being forgotten. It is hoped to arrest this process by cultivating a love for art and literature in the Vernacular.”

When studying the first reason suggested by Plaatje, it seems these ideas came from Shakespearian ideals. Plaatje himself admired Shakespeare’s ability to write emotions devoid of “the monopoly of colour” and admired his “international means of communication”. These traits Plaatje found so admirable seem strikingly similar to his aim to introduce the reader “to the back of the Native mind”.

However, beyond his writing, it seems to be politics where the Shakespearian influence was most consequential. Heywood writes “that for the first African writers, the clash of languages and literature catalysed by the presence of this new society created what he termed a ‘kind of cultural borderland’ where African writers attempted to ‘marry together two different cultural traditions.’ ” Plaatje, allegedly “delighted in exploring this borderland”.

Heywood continues, “Thus, whilst the missionaries called for a complete break with the old society, and generally insisted that no common ground existed between their two literatures, Tiyo Soga, Walter Rubusana, Samuel Mqhayi and others, like Plaatje, sometimes found room for the absorption and silent celebration of African literary forms in European literature (and vice versa). This was most definitely the case.

“This helps explain why, according to Plaatje, African writers sometimes discovered that the two different literary traditions shared ‘a common fund of literary and cultural symbols’.

“Plaatje more accurately captured the real reason for the interest that had developed in Shakespeare, when he stated that the dramas showed that ‘nobility and valour, like depravity and cowardice are not the monopoly of any colour.’ ”

Furthermore, Gray imagines the political value for Plaatje of Shakespeare lay in the fact “that the Shakespeare he had made himself familiar with was an international means of communication; he knew that he could interpret and prophesy quite shockingly about the death of empires in terms”.

He makes these political influences abundantly clear in his Homage to Shakespeare.

“In the beginning of this century, I became a journalist, and when called on to comment on things, social, political or military, I always found inspiration in one or other of Shakespeare’s sayings.”

Plaatje was so taken by Shakespeare that in his fawning homage to him, he described how Shakespeare had allowed his relationship with his wife to flourish.

It is difficult to determine exactly to what extent his love and study of Shakespeare influenced his political views, but it’s clear the ideas of Shakespeare he found most attractive closely mimicked his own political views and desire. Plaatje closely aligned himself with ideals of equality before the law, non-racialism and an unwavering rejection of racial segregation, on both moral and practical grounds.

In personal terms, Plaatje was so taken by Shakespeare that in his fawning homage to him, he described how Shakespeare had allowed his relationship with his wife to flourish. In his deeply emotional, Homage to Shakespeare, Plaatje pens that, “While reading Cymbeline, I met the girl who afterwards became my wife. I was not then as well acquittanced with her language – the Xosa – as I am now; and although she had a better grip of mine – the Sechuana – I was doubtful whether I could make her understand my innermost feelings, so in coming to an understanding we both used the language of educated people – the language which Shakespeare wrote – which happened to be the only official language of our country at the time.

“Some of the daily episodes were rather lengthy, for I usually started with the bare intention of expressing the affections of my heart, but generally finished up by completely unburdening my soul. For command of language and giving expression to abstract ideas, the success of my efforts were second only to that of my wife’s and it is to divine that Shakespeare’s poems fed our thoughts” he continued.

Further on in Homage to Shakespeare, Plaatje wrote, “My people resented the idea of my marrying a girl who spoke a language which like the Hottentot language, had clicks in it; while her people likewise abominated the idea of giving their daughter in marriage to a fellow who spoke a language so imperfect as to be without any clicks. But the civilized laws of Cape Colony saved us from a double tragedy in a cemetery.”

Plaatje would translate Shakespeare plays into Setswana. The Merchant of Venice (Mashoabi-shoabi), The Comedy of Errors (Diphosho-phosho), Much Ado about Nothing (Matsepa-tsapa a Lefeala), Julius Caesar (Dintshontsho-ncho tsa bo-Juliuse Kesara), Othello and Romeo and Juliet, the latter two being left without a Setswana title.

The influence and legacy of the Lovedale publications and translations still have a vivid imprint on the South African cultural scene. The actor and author John Kani once said that upon reading BB Mdledle’s isiXhosa version of Julius Caesar, predictably published by Lovedale Press, he found the original Shakespeare text dull in comparison.

“I felt that Shakespeare had failed to capture the beauty of Mdledle’s writing!”

It’s hard to imagine figures that conjure up more starkly contrasting ideas and imagery. Shakespeare, a symbol of British cultures, transported to her colonies in an attempt to spread British cultures, and wrongly or rightly associated with extreme elitism. Plaatje, an intellectual so opposed to the actions and consequences of the British Empire that he penned an entire novel about it. It seems however, that Plaatje not only acknowledged those contradictions, but he embraced them and used his work to find, to quote Heywood’s thesis, “a common fund of literary and cultural symbols” between cultures.

The perennial debate about whether Shakespeare should be taught in South African schools, or have a place in our national conversation, has consistently raised its head. In many ways, South Africa still faces the same contradictions of those eras – navigating it is still equally treacherous. DM/ ML/ MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider