SPONSORED CONTENT

Looking for a winner? SA banks can outperform amid rising rates

In South Africa and around the world, central banks are hiking their base interest rates and cutting back their asset purchases as inflation rises. Investors are keeping a close eye on the pace and extent of the forecast monetary tightening, concerned that central bank policymakers may err on the side of tightening too much and cutting off growth. With the war in Ukraine and sanctions against Russia sending food and energy prices skyrocketing, central banks’ task of balancing future growth and inflation has been made even more difficult.

Rising interest rates are generally negative for corporate earnings, as borrowing costs become more expensive, while consumer spending slows. However, as with most things in life, there are exceptions to this broad view: history shows that banks can benefit from a rising interest rate cycle, as long as that cycle’s duration and extent remain moderate. This is because they earn a portion of their total income as an endowment – the pot of capital that they have set aside earns interest, so their income rises as interest rates increase. As long as consumers can still repay their loans, and banks’ non-performing loans (NPLs) don’t deteriorate too far, this scenario can be earnings-accretive. If, however, the rate hiking cycle is aggressive, with increases coming too fast and/or too steep for more consumers to be able to afford their debt repayments, banks’ impairment costs will rise and earnings will suffer.

Historically in South Africa we’ve seen that rate hiking cycles of over 150 basis points, spread over a short six-month period, have triggered an increase in NPLs such that banks have had to raise their provisioning levels in excess of what they would earn from the endowment benefit. For now, this is more aggressive than the current projected cycle.

Another important factor to consider is the positive impact that the National Credit Act has made – banks are now much more judicious in their lending practices. Growth in bank financing across various retail lending products on average has remained in the mid-single digits, compared to high teens before the introduction of the Act. It has been even more subdued during the Coronavirus crisis, often lower than inflation (negative in real terms). As a precaution, during the worst of the crisis banks took very large impairments, allowing them to set aside high levels of provisions and did not pay out dividends.

Thanks partly to their more conservative lending practices, banks’ performances have proved to be better than expected, as although NPLs did rise notably, they were amply provisioned and maintained healthy balance sheets. Current provisioning levels are at multiples of what they were during the Global Financial Crisis – in fact, banks have overprovisioned.

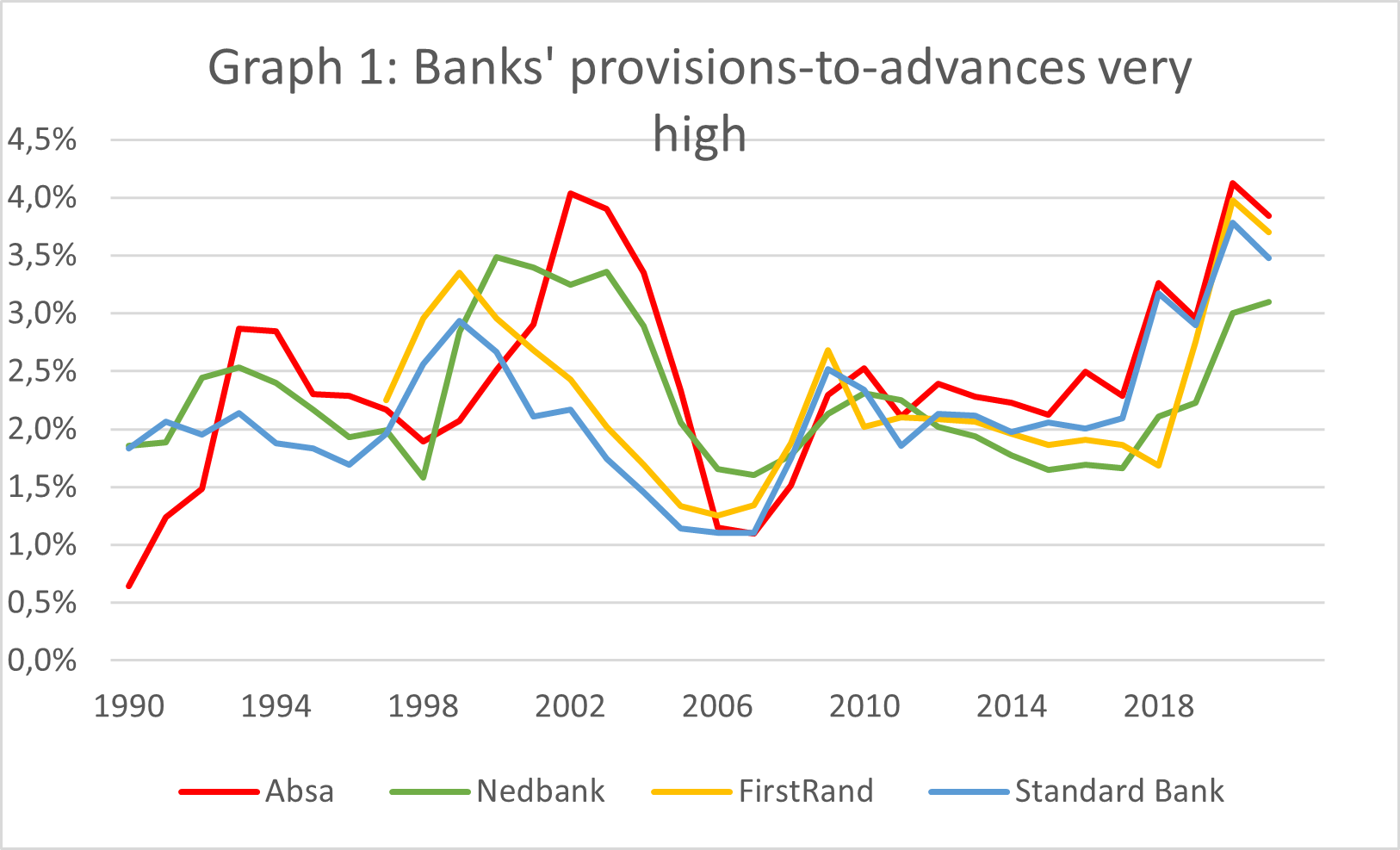

Graph 1 illustrates how banks’ provisions versus their advances are at very high levels compared to their history.

Source: Company data, M&G Investments, data as of 15 March 2022

As such, the market is anticipating that some of these provisions will be written back, improving earnings and capital levels further. Another portion could be retained in case of much worse-than-expected NPLs going forward if, for example, interest rate hikes were to be more aggressive than currently expected. In the unlikely event that NPLs are much worse than anticipated, in theory the banks already have the provisioning in place to cover a substantial amount of that uncertainty.

It is important to note that bank margins were shielded in part from the full impact of the exceptionally low interest rates of the past two years. Although they did pass on a portion of the SARB’s interest rate cuts to consumers, banks benefited from improved asset pricing, which also protected their earnings. The banks have focused on repricing assets and have successfully locked in more attractive margins over the period. Now, as interest rates rise, that buffer may narrow, but banks will benefit from higher endowment earnings. We expect bank margins to continue to expand from these levels.

In short, the above factors make us believe that it is unlikely that banks will need to raise their provisions materially higher during the current rate hiking cycle, thereby largely avoiding additional stress on earnings. They should be among the few sectors to benefit from rising interest rates, carefully compensating for rising risks of non-repayment with higher endowment earnings. Further into the cycle we do think higher rates are likely to dampen some lending activity at the margin, but not to a meaningful degree. More importantly, however, bank stock valuations remain extremely attractive compared to their history and relative to many other sectors, and have excellent potential to re-rate further once the true benefit of their high levels of provisions is considered. In our view, the South African banking sector is one of the best places to be invested going forward given the direction of interest rates. DM/BM

Author: Stefan Swanepoel, Equity Analyst at M&G Investments

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.