This weekend we’re watching

Oscar winner: Alberto Mielgo’s distinctive animation

The Windshield Wiper’s win of Best Animated Short at the 94th Academy Awards is a triumph for animation as an art form, which is still largely misunderstood as an immature medium.

The unseen minds that decide the Oscars — The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences — still don’t get animation. Apparently, neither do the actors who present the awards. Before presenting the award for Best Animated Feature Film at the 94th Academy Awards, Halle Bailey joked that parents are forced by their kids to watch animated movies “over and over and over and over and over.” I see some parents out there know exactly what we’re talking about,” said presenter Naomi Scott.

These quips which posit animation as a medium for children that is tolerated by reluctant adults were echoed throughout the ceremony (to use Bailey’s words) “over and over and over and over and over.” Of the five nominees for best-animated picture, three were Disney and four were for children. The only beacon of hope for a sophisticated approach to animation was Flee, an extraordinary Danish documentary about an Afghan refugee.

But of course, the award went to yet another delightful Disney princess.

In his acceptance speech for Best Animated Short for his film The Windshield Wiper, Alberto Mielgo asserted that “animation for adults is a fact. It’s happening. Let’s call it cinema.” Historically, the Oscars have been willing to take slightly more risks with animated shorts than feature films (less chance of pissing off Disney-Pixar) but even when several unique mould-breaking shorts have been nominated, there has still been a trend of the soppiest and most conventional bringing home the prize, as was the case in the previous awards where If Anything Happens I Love You, a touching but rather clichéd film about a school shooting, won the award over the exquisite hallucinatory Genius Loci and the surreal experimental looping film Opera.

This year, animation lovers will be pleased that the award went to Mielgo, an animator and director whose innovative work has been making waves over the past few years. The Windshield Wiper opens its 15 minutes with a man thoughtfully nursing a cigarette in a smoky café, overhearing millennial Americans loudly discussing relationships and their ideal partners.

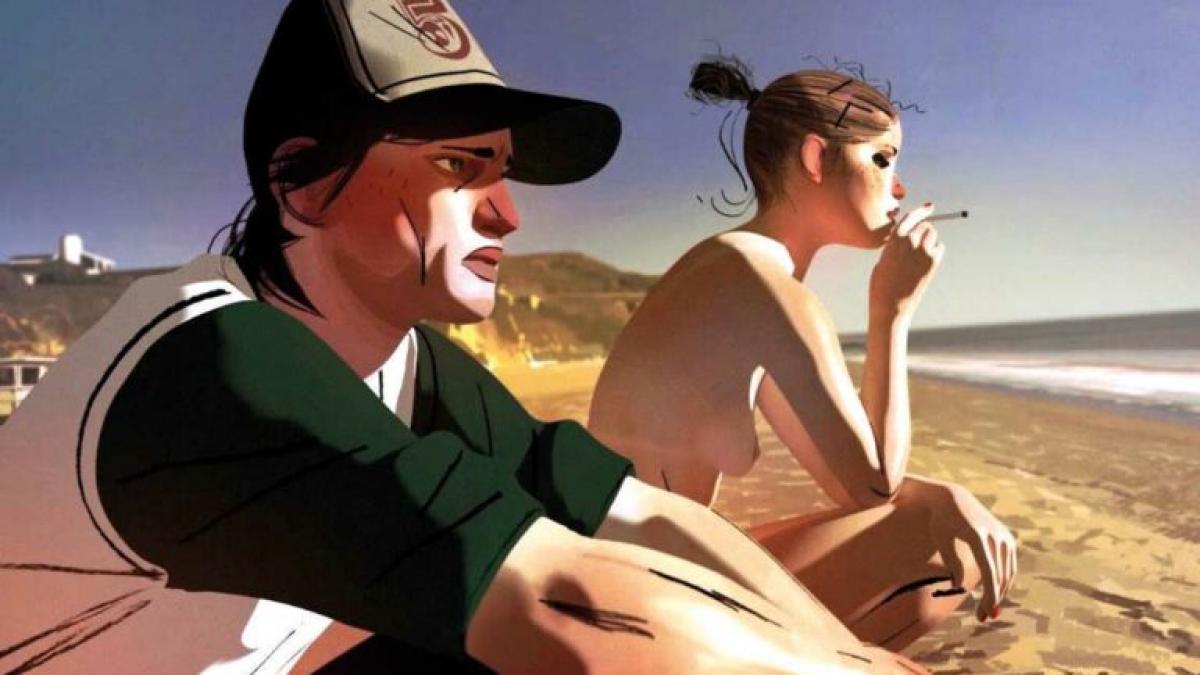

Somehow it’s embarrassing that he must hear their shallow pontificating, but he turns to the camera affectionately and asks us “What is love?” Immediately after this question is posed we are shown the scene of two towers imploding, crumbling and colliding with a roaring crash. This less than romantic metaphor is followed by a vacant-faced couple devoid of passion sharing a smoke on a beach. Clearly, Mielgo is not optimistic about the purity of love.

Production still from ‘Windshield Wiper”. Image: Supplied / Pinkman TV

Throughout the film, we return to the smoking man as he overhears the thoughts of random strangers, but we see that he’s not thinking about it too hard. He knows better than that. As cryptic and darkly poetic as the film is, Mielgo doesn’t expect us to guess what it’s about. He describes it as “a very personal and particular vision on love and relationships.” This emphasis on subjectivity suggests strongly that the smoking man is an embodiment of Mielgo himself.

The Windshield Wiper does return to some of its other characters and stories as well, but for the most part, its scenes are freestanding, linked by a cynical conception of doomed love. Frequently the visuals and audio are not linked in an obvious way and their meaning is left up to the viewer, but one message that comes through unambiguously is a critique of online dating and modern detachment in love.

In a particularly memorable scene, two young adults in a supermarket attentively evaluate the faces of strangers on Tinder, swiping furiously at their phones without any awareness of one another. They each reach for a carton of milk, and a lifetime of meet-cute anecdotes and stories makes us certain that their hands will touch, and they will turn to see one another. Instead, they grope unseeingly at separate cartons, their proximity subsumed by their virtual preoccupation.

As they absent-mindedly attempt to put their cartons in their respective baskets, both of them miss completely — there is comedy in their distraction — but for the most part, their blinkered vision seems tragic, and disrupts the romantic narrative we are so accustomed to.

Production still from ‘Windshield Wiper”. Image: Supplied / Pinkman TV

Mielgo says, “Something that either accidentally or on purpose I always want to do in my projects is to break the repetitive and very successful ‘look’ and pipeline that all the big Giants Corps in animation had been smashing in our faces for the last decade, up to a point that is difficult to differentiate who did what.”

One gets a good sense of what Mielgo is all about by wandering around his website which is visually crisp and well-designed, yet full of grammatical mistakes, swear words and casual, rambling first-person accounts of his astonishing career.

He’s worked on hugely influential projects like Gorillaz and Harry Potter and was the Production Designer for the acclaimed Spiderman: Into the Spider-verse.

Production still from ‘Windshield Wiper”. Image: Supplied / Pinkman TV

Production still from ‘Windshield Wiper”. Image: Supplied / Pinkman TV

Mielgo’s style is exaggerated and messy. The aesthetic is somewhere between digital art, pastel comic sketch, and oil painting. His images are built on the skeletons of real footage, making them life-like, but they’re exaggerated in dimensions, perspective and colour. His huge colour palette and range of lighting techniques brings fantastical magic to everyday scenes.

If nothing else, Mielgo’s imagery will stick in your mind. He doesn’t shy away from nudity and uses cinematic techniques like blurs which imitate a camera struggling to focus, creating dramatic scenes that often climax with a single beautiful frame. If you enjoy his unique, fast and loose style check out his personal favourite of his films, The Witness — an animated film from the first season of Netflix’s sci-fi anthology Love, Death and Robots. The Witness deservingly won three Emmys.

Production still from “The Witness” in “Love Death and Robots”. Image: Supplied / Netflix

Production still from “The Witness” in “Love Death and Robots”. Image: Supplied / Netflix

The Windshield Wiper explores so many aspects of our desire for human connection in a mere 15 minutes. The fatuous nature of texting; the emotional disassociation of modern dating; the intense pain of unrequited feelings; the animalistic objectification of desire; the implied dichotomy between male and female perceptions of love… The list goes on.

As the scenes progress, there is more variety in the emotions embodied, and we get the sense that Mielgo is actually romantic about love in some ways.

As the film comes to a close, the smoking man looks at the camera as if preparing to impart to us his wisdom about what love is, but then he seems uncertain and thinks better of it. He does eventually provide an answer, but that moment of hesitation communicates that he’s not claiming to know for sure. Just like Mielgo’s film, the definition of love is subjective. DM/ ML

The Windshield Wiper is available on Youtube. You can contact This Weekend We’re Watching via [email protected]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.