BOOK EXCERPT

The World: A Family History – on the families, kingdoms and civilisations that have shaped our world

‘The World: A Family History’ by master storyteller and internationally bestselling author Simon Sebag Montefiore tells the story of humanity from prehistory to the present day through the one thing all humans have in common: family.

The book begins with the footsteps of a family walking along a beach 950,000 years ago, and from there Montefiore takes the reader on an epic journey through the families, kingdoms and civilisations that have shaped our world.

The World is as enthralling as fiction, capturing the story of humankind in all its joy, sorrow, romance and cruelty.

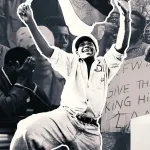

The following excerpt follows the rise and fall of Shaka Zulu, 19th-century king of the Zulu Kingdom, his age-mate Moshoeshoe, leader of the Sotho, and the emergence of the present shape of southern Africa. Here is an excerpt.

***

As Shaka’s conquests intensified the Mfecane, he was just one player in a multi-ethnic tournament for power and resources. To the north-east, the Portuguese forged a unique model of European empire. Portuguese kings granted titles and estates to Luso-African warlords, the prazo senhors, who ruled alongside African magnates and formed their own private armies of African slaves – chicundas – in Zambezia. Afro-Portuguese lords of Zambezia – the prazeiros, commanding armies of African colonos – hunted deeper into Africa for cattle, slaves and ivory to sell in Lourenço Marques (Mozambique); further north, Omani and Swahili slave traders hacked their way into central Africa, selling their captives around the Indian Ocean as Mehmed Ali raided into Sudan. To the south, the mixed-race Griqua raided into the northern Cape; Xhosa kings conquered the east Cape; and behind them came the Dutch and the British.

The Dutch traders of the VOC had founded Cape Town, where they settled thousands of poor Boers – farmers, devout Calvinists – who soon encountered the hunter-gatherer Khoikhoi (Bushmen or Hottentots to the Europeans), descended from the original inhabitants of the continent, pushed southwards by the Bantu who migrated from west Africa. The Dutch imported slaves from Dahomey, Angola and Mozambique to work their plantations while breaking the Khoikhoi, who, crushed between Bantu and Dutch, decimated by smallpox and reduced to indentured labour close to slavery, almost ceased to exist. The settlers, who called themselves Afrikaners, expanded northwards and eastwards, thus encountering the Nguni, herders of long-horned cattle, who were moving south conquering their own kingdoms.

The Afrikaners developed into skilled frontiersmen, who raided the herds and hunted elephants for ivory, but they also settled with African women with whom they had children, sometimes living more like Nguni royalty than Europeans. They became expert fighters in mounted units called commandos, and trained their mixed-race sons to serve as auxiliary fighters. When the British seized the Cape, it was a colony of 75,000 people – 15,000 semi-hostile Afrikaners, 13,000 black slaves, 1,200 freedmen and the rest mixed-race Khoikhoi-Dutch Griqua, known as the Bastards. As new British settlers arrived in the Cape, moving north and eastwards, they encountered resistance from the amaXhosa kingdom led by Tshawe warrior kings Ngqika, Hintsa and Mgolombane Sandile. The Xhosa were formidable fighters whose acumen is often neglected by historians: they halted the British empire for seventy years. Now in 1818 as the British were fighting the amaXhosa under Hintsa, a group of frontiersmen founded Port Natal on the east coast and travelled to Shaka’s capital kwaBulawayo. The king mocked their strange fair hair – comparing it to cattle tails – but granted them rights to the port and recruited them as military advisers. Yet Shaka’s conquests were reaching their limit: in the east he was defeated.

In 1824, while the British hunters were still in the capital, Shaka was dancing when a would-be assassin speared him in the side. Shaka hunted down the hitmen, who were beaten to a pulp by the people, then he massacred the Qwabe tribe whom he decided to blame – though he rightly distrusted his own family. In 1827, his mother Nandi died mysteriously. She had disapproved of his purges, and may have protected a male baby born of his concubines: he either killed her in a rage or had her killed, like Nero. Zulu royalty were buried sitting up supported by the bodies of sacrificed henchmen, servants, concubines, strangled or buried alive. Killing anyone suspected of disloyalty, Shaka supposedly killed 7,000 people. After Nandi’s death he appointed his aunt Mnkabayi as Great She-Elephant.

As the British and Afrikaners probed Zulu lands, and Shaka launched his terror, southern Africa was in ferment. In 1828, needing another victory, Shaka ordered an expedition against Soshangane, formerly one of Zwide’s generals, who led the tribe founded by his grandfather Gaza eastwards to find their own realm. Emulating many of Shaka’s military tactics, Soshangane routed the Zulus, weakening Shaka. “I’m like a wolf on the plain, at a loss for a place to hide his head in,” Shaka said, encouraging the diviners to smell out witches among his half-brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana. Great She-Elephant Mnkabayi began to suggest that he was mad and had killed his mother. But while he was protected by his devoted bodyguard inceku Mbopha, no one could touch him.

Less meteoric than Shaka but more remarkable was Moshoeshoe, born the same year as the Zulu, leader of the Sotho, herdsmen who suffered bitterly from predations by Nguni and Griqua. Moshoeshoe led his Sotho on a perilous migration to the Qiloane plateau (Lesotho) where he created a stronghold – the Night Mountain, said to grow in the day and shrink in the night – where he withstood attacks by all his rival leaders to create a rich cattle-owning kingdom. Cleverly exploiting the British, he offered himself as a balance to Afrikaners and Zulus, buying rifles and hiring a French missionary, Eugène Casalis, as consigliere.

In a fifty-year reign (it ended in 1870), Moshoeshoe defeated the British, Afrikaners, Zulus and Ndebele. More humane and constructive than Shaka, he was ‘majestic and benevolent. His aquiline profile, the fullness and regularity of his features, his eyes a little weary made a deep impression upon me,’ wrote Casalis. ‘I felt at once I was dealing with a superior man, trained to think, to command others and, above all, himself.’ Out of these wars emerged the present shape of southern Africa.

When the men died, the estates were inherited by female mixed-race potentates: in Mozambique these Luso-Africans were known as the Zambesi donas. Dona Francisca de Moura Meneses was a mixed-race heiress who, born in 1738, ruled a massive Zambezian estate, owning several thousand slaves, presiding over many thousands of free Africans and deploying a private army that at times threatened the Portuguese governor. The Africans called her Chiponda – She Who Tramples All Underfoot. There was no equivalent of the Zambesi donas back home in Europe, let alone in any other empire.

Mosheshoe’s family still rules Lesotho. Shaka accused Mzilikazi, a grandson of Zwide, of keeping cattle prizes for himself. The punishment was death. Mzilikazi escaped with his Ndebele clan into Transvaal and then Zimbabwe, where his Matabele kingdom confronted the Shona: the two tribes dominate Zimbabwe today. Shoshangane turned his victory into the Gaza kingdom in southern Mozambique, forcing the Afro-Portuguese prazeiros to pay tribute. Sobhuza, ruler of the Dlamini, migrated to avoid Shaka, founding Swaziland – Eswatini – named after his son and successor Mswati. It likewise is still ruled by his family. DM/ ML

The World: A Family History by Simon Sebag Montefiore is published by Orion (R830). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

This story was first published on 22 November 2022.

British historian and author Simon Sebag Montefiore is on tour in South Africa on Sunday 26 March, 10:00 for 10:30 at the Rabbi Cyril Harris Community Centre. Contact [email protected] to purchase a ticket (R120).

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Comments - Please login in order to comment.