JUSTICE OP-ED

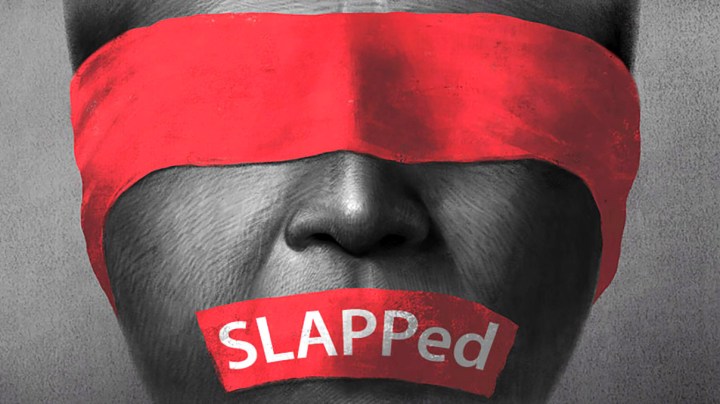

Our courts must tackle the practice of ‘Slapping’ human rights defenders into silence

A recent Constitutional Court appeal hearing on a high court judgment that South African common law does recognise a Slapp suit defence as an abuse of court process, highlights the urgent need for these suits to be addressed as tools that impair the right to freedom of expression and access to justice, thus posing a threat to democracy.

On 17 February 2022, the Constitutional Court heard a direct appeal against the 2021 judgment by Western Cape High Court Deputy Judge President Patricia Goliath that Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation (Slapp) defences are recognised and valid in our law.

The growing popularity of Slapp suits has warranted many countries to develop laws to counter them. These are generally referred to as Slapp defences or anti-Slapp laws. The Constitutional Court was asked to consider whether South African common law recognises a Slapp suit defence as an abuse of court process, and if not, whether it was possible to develop the common law in terms of section 39 of the Constitution to recognise such a defence.

On 17 February 2022, the Constitutional Court heard a direct appeal against the 2021 judgment by Western Cape High Court Deputy Judge President Patricia Goliath that Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation (Slapp) defences are recognised and valid in our law. (Photo: Twitter)

Goliath’s 2021 judgment was made in a case involving long-running defamation action by an Australian mining company and its South African subsidiary against six South African environmentalists and social activists.

Recognition

In her judgment, Goliath had held that our law does recognise a Slapp defence — court action launched by state and non-state actors — including wealthy, powerful corporations (and individuals) — against ordinary people who criticise them and try to be part of the decision-making process on issues that affect their lives.

She held that Slapp suits are designed to turn justice into weapons to intimidate dissenters who work in the public interest. She highlighted that the respondents do not have the same financial muscle as the mining companies and recognised that the litigation simply emerged because the respondents spoke out. She held that:

“It appears that the defamation suit is not genuine… but a pretext to silence its opponents and critics” and that this constitutes an abuse of the courts’ processes.

Of note, Goliath remarked that the case brought by the mining companies “matches the DNA of a Slapp suit”. She thus rejected the argument made by the mining companies that our law does not recognise a Slapp defence. It is worth remembering that Goliath did not make a finding on the merits of the case, ie she did not decide whether the Slapp defence should actually succeed. She was adjudicating a technical argument (an exception) that a Slapp defence was not recognised in law.

Aggrieved by this outcome, the mining companies directly knocked on the doors of the Constitutional Court. The crucial question before the court is this: does our common law recognise a Slapp defence? If it does, then the decision of Goliath stands. However, if the answer is no, the question then becomes: should the court develop the common law to accommodate such a defence?

Background

In 2017 two mining companies, South Africa-based Mineral Sands Resources (Pty) Limited and its parent company, Australia-based Mineral Commodities Limited, sued three environmental lawyers (Christine Redell, Tracey Davies and Davine Cullinan) and three community activists (Cormac Cloete, Mzamo Dlamini and John Clarke) for a total of R14.25-million on the basis that they defamed the mining companies. The mining companies are involved in the exploration of mineral sands projects in South Africa, namely the Tormin Mineral Sands Project and the Xolobeni Mineral Sands Project.

The discovery of rare minerals in the sands has divided the Xolobeni community. (Photo: Daniel Steyn)

The mining company also sought a punitive cost order against the Centre for Environmental Rights, a public interest organisation that provides free legal representation to environmental activists and mining-affected communities. In a poorly disguised Slapp action, the mining company argued that legal NGOs, like the centre, should be prevented from doing so as it constitutes a direct and substantial interest in the proceedings and the outcome, which constitutes an unethical conflict of interest. While this demand was eventually withdrawn, it sent an ominous warning to all public interest lawyers representing human rights defenders.

Human rights defenders abused and intimidated

Slapp suits can take many forms and include the abusive use of criminal and civil court procedures to intimidate, silence, censor, scare and prevent disclosure and broader public discourse and debate. Invariably, courts and legal processes become weaponised as sites of censorship by tying people up in lengthy and expensive court action that drain the litigants’ money, energy and enthusiasm.

Generally, a Slapp suit is initiated to censor and intimidate those who criticise certain classes of people, such as human rights lawyers, academics, journalists and community activists (also known as human rights defenders). This is done by burdening them with legal costs until they retract their criticism.

Generally, plaintiffs in Slapp suits claim for significant, and perhaps outlandish, financial compensation, which is why it is ordinarily argued that the plaintiffs do not genuinely intend to win the case. The merits of the case are generally weak, untenable or exaggerated. They are merely litigating to financially punish public dissenters and remind them of power imbalance by tying them up in protracted, expensive legal processes where a veritable forest of interlocutory paper is generated.

Slapp suits are insidious and generally characterised as an attack on freedom of expression. They tend to undermine fundamental tenets of democracy by discouraging public participation in matters of social or political significance. They remind the litigants of the disparity of power and resources between the two parties. Those with power and resources can litigate for as long as they want and raise as many meritless arguments as their brilliant advocates can conjure, clogging up our courts.

Refusing to be silenced

The respondents had made various public statements about the mining companies’ mining activities and the deleterious impact on the development of the Wild Coast. Some of the statements called out the mining companies for failing to adhere to mining and environmental laws, which led to a cliff collapsing at some point in 2015.

Members of the Mfolozi Community Environmental Justice Organisation protest against Tendele’s coal mine operations at Somkhele, KwaZulu-Natal. (Photo: Rob Symons)

Moreover, the mining companies’ proposed mining in Xolobeni has caused unrest as many community activists are simply against their ancestral land being used for mining purposes. The mining companies belaboured each statement as defamatory and thus claimed damages for these statements, or alternatively, the publication of an apology.

Specifically, the mining companies brought three defamation actions. The first defamation claim was brought against Redell, Davies and Cullinan for comments they had made at the University of Cape Town’s Summer School in 2017 while giving lectures. Mineral Sands and its director seek damages in the amount of R750,000 and R500,000 respectively.

In the second defamation claim, Dlamini and Cullinan had made several statements during a radio interview, criticising the companies’ mining activities. Mineral Commodities and its CEO took offence and sued Dlamini and Cullinan for R1.5-million each.

The third defamation claim concerns criticisms and comments made by Clarke in two of his books as well as radio interviews, YouTube videos and other platforms. For his criticisms, Mineral Commodities and its CEO demand damages in the sum of R5-million each.

Two special pleas

In response, the respondents raised two special pleas.

They contended that first, for-profit companies cannot sue for defamation as they do not enjoy the right to dignity.

Second, each of the defamation actions constituted an abuse of process aimed at discouraging, censoring and intimidating the respondents and members of civil society, especially those who publicly criticise the mining companies (the Slapp special plea). This article restricts itself to the Slapp defence portion of the case.

Unsurprisingly, the mining companies posited that the Slapp special plea does not give rise to any defence in our law.

The strategy of targeting a group of human rights defenders has the chilling effect of silencing them, infringing on their right to freedom of expression as set out in section 16 of the Constitution, and it may also intimidate future dissenters and discourage them from speaking out.

Constitutional Court arguments

During the landmark Constitutional Court appeal hearing, counsel for the mining companies, led by advocate Peter Hodes SC, argued that our law does not recognise such a defence and if such a defence were to be recognised, it should be done by the legislature and not the courts.

Part of the mineral sands extraction by the Tormin mine on the West Coast. (Photo: John Yeld)

He further contended that the mining companies have the right to access courts (as entrenched in section 34 of the Constitution), and a mere claim of ulterior motive alone, to the exclusion of the merits of a claim, is insufficient for an abuse of process dismissal. It is argued that the merits are relevant in an abuse of process analysis. With this in mind, Hodes alleged that the respondents have failed to provide averments necessary for upholding a Slapp defence.

Counsel for the respondents, led by Geoff Budlender SC, argued that the purposes of the court processes are to establish the truth and enable parties to vindicate their rights. It is an abuse of those processes to use them to achieve an ulterior purpose. The respondents contended that the Slapp defence is recognised under the common law abuse of process doctrine. However, if it is not, it would be necessary for the court to develop the common law to recognise it.

Budlender argued that the defamation claims were brought with the primary intention to censor criticism. The only logical explanation for the significant financial claim against the human rights defenders is that the mining companies want to censor and intimidate the respondents. There was no evidence that the mining companies had suffered any financial loss due to the alleged defamatory remarks. This demonstrates that the ulterior motive inspires the litigation to silence and censor.

Furthermore, Budlender argued that the respondents submit that abuse of process is a court-created doctrine to protect its own processes. Consequently, the legislature does not need to interfere and introduce legislation. In relation to the mining companies’ argument about their right to access to courts, Budlender held that the right to access to courts cannot be used to perpetuate an ulterior purpose to silence and censor.

Friends of the court

Southern Defenders (the Southern African Human Rights Network) and the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (Cals) were admitted as amici curiae in the matter. Cals made submissions in support of a Slapp defence in our law. They contend that there is, however, a distinction between a Slapp defence and abuse of court process, the former being more nuanced than the latter. As a result of this distinction, there should be a separate test for determining a Slapp defence. This test is two-pronged: first, there must be a consideration as to whether a case has merit and, second, whether it would be in the interests of justice to continue with the case.

Advocate Jatheen Bhima, lead counsel for the Southern Defenders, argued that the network aligns itself with the respondents’ arguments. He contended that the defamation suit is litigation targeted at quelling dissent and the silencing of environmental rights defenders who speak out against the operations of corporations and indeed meet the criteria of Slapp.

To this end, he argued that the court must interpret and consider this type of litigation through the lens of a range of international instruments that are both binding and non-binding on South Africa. The high court judgment must be understood through the international landscape.

Section 39(1) of the Constitution puts an injunction on courts to consider international law when interpreting the Bill of Rights. Southern Defenders highlighted the international law obligations placed on South Africa by international law instruments such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which has taken issue with the harassment of activists who work in the environmental and mining sector.

Another international law instrument that the court should consider is the Compendium on the Legal Protection of Human Rights Defenders in Africa, produced by the African Commission Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders and Focal Point on Reprisals in Africa.

Urgent action needed

There is an urgent need to address Slapp globally and domestically. It is a form of legal intimidation with the sole aim of subverting public participation by stifling debate. Slapp suits not only impair the right to freedom of expression and access to justice, but they pose a threat to democracy.

Courts have the inherent power to regulate their own processes and to prevent the abuse of court processes for ulterior purposes. There appears to be no compelling reason why our courts should not develop the common law abuse of process doctrine to recognise a Slapp defence in light of the growing Slapp suits against human rights defenders.

International law requires South Africa to provide a safe and favourable environment for the work of human rights defenders to promote and protect economic, social and cultural rights. The recognition of a Slapp defence is an important building block in the broader protection framework. DM/MC

Sfiso Nxumalo is a DPhil in Law Candidate at the University of Oxford and holds an LLB (Wits) and BCL (Oxon).

The Southern Defenders is the regional human rights defenders (HRDs) network comprising representatives from human rights organisations in 10 countries in southern Africa. It was established in February 2013 with the primary mandate of coordinating the protection and security of HRDs in the region, and to enhance their ability to work in their particular countries, in the face of state-driven or supported repression.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.