SIGN OF THE TIMES

What exactly is Democracy? Are we even doing it right?

The South African democratic system has been a central part of our nation’s identity since the 1994 elections. Why is this significant, and is our democratic standing in trouble?

“Voters’ decision to not even bother casting their ballots presents an indictment on politicians, public representatives and how (little) electoral democracy serves them, and their daily lives,” wrote journalist Marianne Merten in an article about the low voter turnout in the 1 November local elections.

This year’s 47.43% voter turnout signifies a 10% drop from 57.94% in 2016, continuing a downward trend that has been going on for some years. Wayne Sussman of Daily Maverick, agreeing with Merten, writes that this historically low turnout signals “continued plummeting public trust in public-elected institutions and electoral democracy”.

The causes of this can only be theorised but are likely to be a soup of terrible ingredients: Corruption, lack of public services, the Covid-19 pandemic and technical difficulties, with a sprinkle of violence and bitterness on top. What is clear, however, is that the days of the great queues that were emblematic of South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994, electric with hope and cutting snake-like shapes along the earth, are long over.

A sample ballot paper from the 1994 general election in South Africa is seen at a press preview of “Mandela: The Official Exhibition” at 26 Leake Street on February 07, 2019 in London, England. (Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images)

South Africa is certainly not the only nation seeing this kind of (non)action. Many parts of the world are concerned about the state of their democratic regimes. In this New York Times article, titled “How Stable Are Democracies? ‘Warning Signs Are Flashing Red’”, Harvard lecturer Yascha Mounk outlines the reasons he believes that “liberal democracies around the world may be at serious risk of decline.”

If we are in a moment of democratic crisis – if our democracy and its future is, as evidence seems to point towards, indeed on shaky ground – what does this mean for us, the citizens who have to live with the daily realities of existing in a society where democracy is failing?

To fully comprehend the ground on which we now stand, as well as what might be in store for us if that very ground falls away beneath our feet, it is helpful to take a small step back and revisit the basics – the beginning of all of this. What exactly is this democracy that we are all so worried about protecting? Where did it come from? What does it look like in the South African context? And most importantly, why does it matter? Why should we care?

The beginning…

While there is some evidence that there were informal versions of democratic organisation in prehistoric times, the concept was formally coined in the 5th century BCE by ancient Greeks to describe the means of political organisation that were being used in some of the empire’s city-states, notably Athens.

The word itself derives from the Greek “demokratia”, which directly translates to rule by the people (demos means people, kratos means rule.) The central idea is that the people themselves, the citizens of the democratic regime, are the ones who govern. In other words, they make and enforce the rules (and consequences of breaking those rules) which they themselves, along with other citizens, must abide by.

Nelson Mandela casting his vote during the 1994 general elections on April 27, 1994 in Durban, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Sunday Times / Richard Shorey)

In ancient Greece, the form that this early democracy took was called direct democracy, meaning that citizens voted directly on each policy initiative brought to the electorate – every little rule change was to be decided upon with a vote. Keeping in mind, the Ancient Greek city-states practising this form of democratic rule were minuscule compared with nation-states like South Africa (not to mention the US). Athens, for example, had a population of about 140,000 in the 5th century BCE. Today, South Africa’s population sits at about 59 million, while the US counts a whopping 329.5 million people. For this reason, most contemporary democracies use a form called representational democracy (to be expanded upon later).

“From the perspective of a citizen of ancient Athens, the governments of significant associations such as France or the US may not have appeared democratic at all.”

To turn back to Athens, while the city had a total population of about 140,000, only 40,000 were officially considered Athenian citizens. This is because the Ancient Greeks at the time only permitted voting rights to adult men (men over 20 years old) who were both free and hereditarily tied to the city-state. In other words, women, children, slaves and foreigners were excluded from the democratic process; they were not seen as “capable, voting humans”.

Which brings to the fore a core question that continues to plague even the democracies of today: Who constitutes the demos, the people? Who is recognised as a citizen? Thankfully, contemporary democracies no longer sanction slavery or exclude women from the voting process – although the picture is not always as clear as stated – yet, the question still stands in regard to immigration laws and members of the population who are generally not recognised by the state (the undocumented, for example.)

How long does a person have to live in a country to be considered a citizen? (In South Africa, the official answer is five years, but chat to any foreign Uber driver who has lived in the country for double that time and is still in a struggle for citizenship with Home Affairs and you will realise that the reality is a much more complicated thing.) And should democratic decisions include the opinion of those who are considered mentally hampered? Drug addicts? Prisoners?

The fact is, democracy today looks very different from its origin in Ancient Greece. As the Encyclopaedia Britannica puts it, “from the perspective of a citizen of ancient Athens, the governments of significant associations such as France or the US may not have appeared democratic at all”.

The ideal democracy

During the 20th century the world saw a huge increase in democratic institutions, and by the 21st century, more than one-third of the world’s nominally independent nations possessed democratic institutions. Encyclopaedia Britannica concludes that by the mid-20th century, “no system whose demos did not include all adult citizens could properly be called a democracy”.

By this point, too, most democracies were nation-states and used a representational method. In other words, because of the increase in the size of the democratic institutions, the political system morphed so that citizens could vote for trusted representatives to make important decisions for them, instead of constantly voting on each decision themselves, like the Ancient Greeks did in the direct democracy of 5th-century Athens.

It is clear then that since its inception, democracy had profoundly transformed. Not only had it changed from its original Grecian form, but it had also branched into multiple variations. Democracy in the US looked different from democracy in the UK, which did not exactly mirror the democracy of New Zealand or France. It was (and continues to be) a constantly shifting and amorphous concept.

It is important to note, however, what the core ideals of democracy are in order to understand what forms of government can correctly be termed a democracy, and what we wish an ideal democracy to look like.

South African women are seen wearing their national flags in celebration of Freedom Day in Trafalgar Square on April 27, 2004 London England. (Photo by Graeme Robertson/Getty Images)

Women celebrate during the day-long Freedom Day in Trafalgar Square on April 27, 2004 London England. (Photo by Graeme Robertson/Getty Images)

Democratic core ideals

According, once again, to Britannica, the ideal democracy would include four crucial parts. One, effective citizen participation (making proposed policies and people’s views on said policies known to the public.) Two, equality in voting (all citizen votes on any issue must be counted as equal). Three, an informed electorate (the people who constitute a democratic regime must have the opportunity to learn about policies, their likely consequences, and their alternatives). And four, citizen control of agenda. In other words, the people (or their representatives) must be allowed to choose what issues are important and must be discussed and/or changed.

In line with these ideals are the fundamental rights that should be inherent to every person living in a democratic society. These must include (but are not limited to) the right to communicate with others, the right to have one’s vote counted equally with the votes of others, a right to gather information, a right to participate on equal footing with other citizens, and a right, alongside other members of the democracy, to exercise control of the agenda.

But at the very heart of democracy lies the ideal of freedom. Defined in the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “the power to do what you want to do: the ability to move or act freely”, the concept of freedom makes up the core of what democracy strives to be: A place where each person is permitted to act, move and think as freely as possible. If this is to be achieved, as this article in Time relates: “Freedom requires enhancing people’s voice in government.”

In order for a democracy to work, for the people’s ideas of what freedom looks like to manifest, the citizens of a democratic association must actively believe and participate in the system.

John Laird, in Democracy and Personal Freedom, writes that “the primary meaning of freedom is ‘freedom from’, that is to say, the absence of restriction and impediments”. In conversation with democracy, political freedom includes three important pillars: Freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly (or the freedom to gather and organise politically. With these combined freedoms, the citizens of a nation-state should, ideally, have the ability to know about the way they are being governed, voice valid and varied opinions on a matter at hand, and vote/organise to incite change. This means that the public has a massive influence on the boundaries within which their freedom can flourish.

John Dewey, an American political philosopher, believed that democracy alone “provides the kind of freedom necessary for self-development and growth – including the freedom to exchange ideas and opinions with others, the freedom to form associations with others to pursue common goals, and the freedom to pursue one’s own conception of a good life”.

Dewey also believed that participation was absolutely paramount to a working democracy; which brings us to a crucial point: In order for a democracy to work, for the people’s ideas of what freedom looks like to manifest, the citizens of a democratic association must actively believe and participate in the system.

In 1994, after a long and gruelling struggle, the first democratic elections that took place in South Africa became an emblem of the fight for justice and freedom worldwide.

Britannica states: “The minimum condition for the continued existence of democracy is that a substantial proportion of both the demos and leadership believe that a popular government is better than a feasible alternative.” For the people to rule, the people must be involved.

Which is why, when the voter turnout in South Africa hits an all-time low, and the trust in leadership is all but dissipated (due to the leadership’s apparent disregard for democratic ideals), we begin to worry that our democracy is indeed in a state of crisis.

South African residents wait in a long queue at a voting station in Sebokeng, Johannesburg, South Africa, on 18 May 2011 to cast their votes in the municipal elections. (Photo by Gallo Images/Frank Trimbos)

Democracy in South Africa

During the apartheid regime, restrictions and impediments abounded for people of colour. The vast majority of the South African population were anything but free.

The existence of things like passbooks, racial segregation of living areas and facilities, limited access to welfare and political rights for people of colour, and draconian security legislation that served to police all of these rules, meant that most of the population was restricted in movement, the right to choose where they resided, what they learned, and much, much, much more; in addition, the media and the press were government-controlled and highly censored.

The disregard for human rights during apartheid was violent and blatant. In fact, in the late 20th century, South Africa was the last great and un-decolonised settler state in Africa. The stakes were higher than just the nation itself; South Africa was one of the last bitter reminders in the world of the horrors of imperialism and slavery.

This is why in 1994, after a long and gruelling struggle, the first democratic elections that took place in South Africa became an emblem of the fight for justice and freedom worldwide.

Voters standing in long queues during the 1994 general elections in South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

ANC members campaigning during the 1994 general elections in South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

While the peaceful and fair elections were, in themselves, a moment of pride and hope, the Constitution, the fundamental principles that underlie the democratic government of independent South Africa, furthered the potential for what looked to be an incredible future.

At the time of its inception, independent South Africa’s Constitution, signed into law on 10 December 1996 in Sharpeville, was hailed as one of the most progressive in the world and enjoyed high acclaim internationally.

“We, the people of South Africa, recognise the injustices of our past […] and believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.”

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the late US Supreme Court justice, called the new South African Constitution “a deliberate attempt to have a fundamental instrument of government that embraced basic human rights [and] an independent judiciary”.

But why was (and is) our Constitution considered so progressive? For one, it clearly centred on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights. It also contained, for its time, obligations and provisions that were unprecedented, such as explicit references to the acceptance of diversity in race and sexual orientation. It is highly lauded for its clear assertions on both social and environmental rights.

In direct opposition to the restraints and violence of the apartheid regime, the preamble to the Constitution states:

“We, the people of South Africa, recognise the injustices of our past […] and believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.”

This central and aspirational spirit of inclusion was mirrored in the very development of the Constitution, which was the product of a massive public participation programme conducted throughout the country. There was a public call for anyone, any member of the South African public, to submit ideas and recommendations for inclusion in the Constitution. We, South African citizens, took a large and active role in setting the precedents according to which our newly independent state was to be governed.

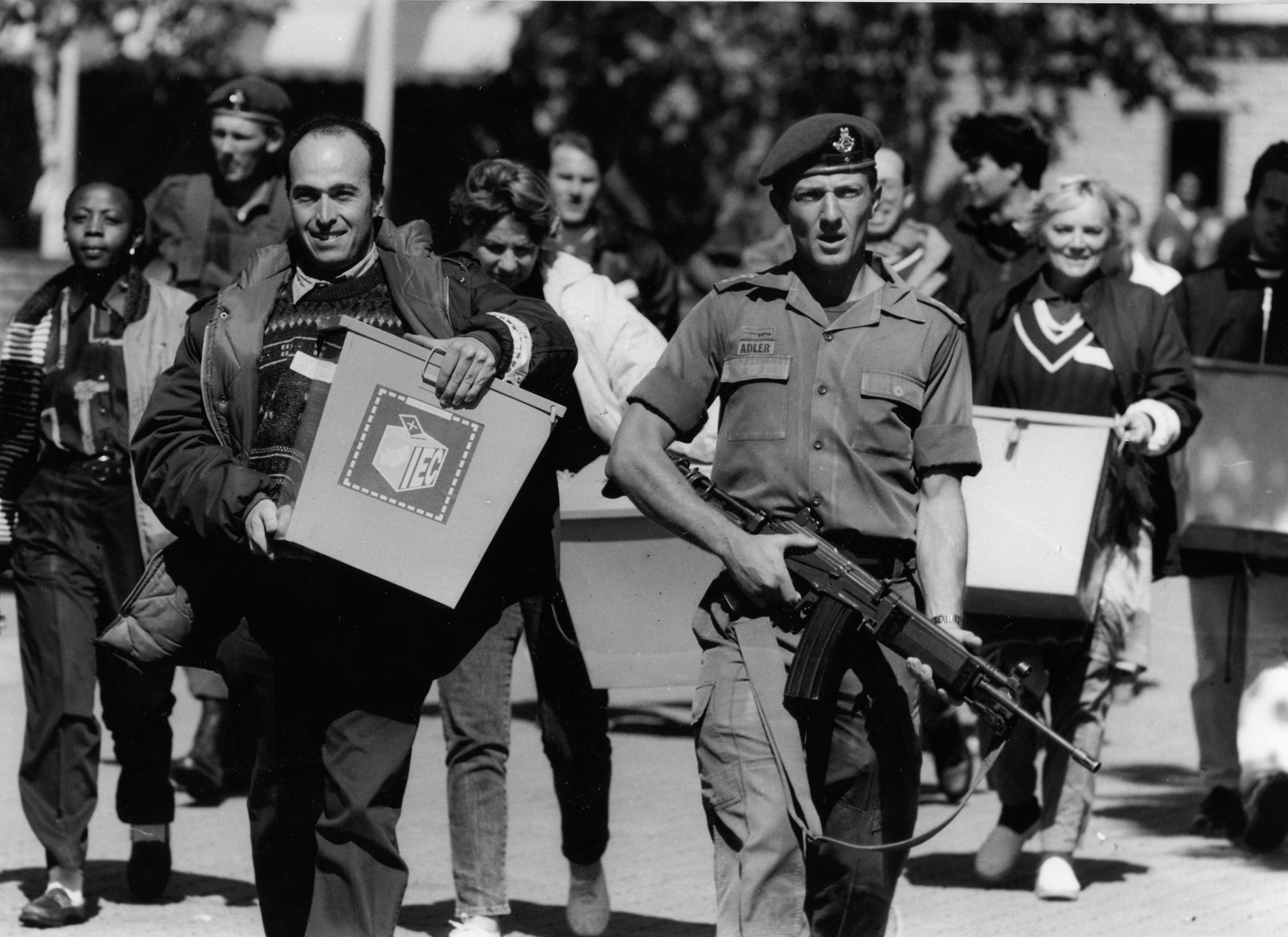

Ballot boxes being escorted under guard on May 1, 1994 in South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Avusa / Allen van der Linde)

Voters standing in long queues during the 1994 general elections in South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

Voters standing in long queues during the 1994 general elections in South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

Why should we care about democracy?

Pericles, an ancient Greek statesman and general during the Golden Age of Athens, was alleged to have stated that democracy will “afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if to social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way; if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition. The freedom which we enjoy in our government extends also to our ordinary life.”

This feels imperative in a country as diverse as South Africa, where the need for multiple voices and opinions to be heard is a requirement. Looking back on the cruelties of apartheid, on the vast numbers of people who were subjected to inhumane treatment, it is not hard to understand why a democratic (or at least the attempts at one) is an alternative that we must continue to strive for.

Perhaps Winston Churchill’s words are useful here: “Democracy is the worst government, except for all the others.”

There is no denying that the South African political climate as it stands is riddled with problems and is far from the idealistic vision its Constitution paints. But there is also no denying that the base on which we are operating is far superior to the form that it took during the colonial and apartheid years.

The point here is not to debate what could have made this epic dream of an ideal South African democracy go wrong, but rather to remind ourselves that, as a nation, we made a concerted effort to imagine one at all. There was once a will, but we have lost sight of the way.

Perhaps we can find, in the seeds of past hope, a determination to grow more. Things have not gone to plan, that much is clear. What is also clear is that the people of South Africa have united for democracy before, and we can do so again. Or, if not in the name of democracy, then perhaps in the name of something even better. DM/ML

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8854″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Personal opinion:

Democracy does not work where 70% of the population cannot write a 2 page essay. Let alone understand what debt/GDP ratio is. Waste of time.

One, effective citizen participation – maybe.

Two, equality in voting – yes.

Three, an informed electorate – no.

And four, citizen control of agenda – no.

37,5% success rate = MAJOR PASS! We have passed the Democracy test! (Ask any new SA matriculant!)

Is gerrymandering considered democratic?

In his book ‘Against Democracy’ Professor Jason Brennan from Georgetown University, describes three types of voters. He distinguishes between voters that are hobbits, hooligans and Vulcans. Vulcans are noted for their attempt to live by logic and reason with as little interference from emotion as possible

“Hobbits are those who did not bother to learn about politics, and therefore vote in full ignorance; Hooligans are those who follow their own party with the devotion of sports fans and adhere to a certain party, irrespective of past performance and future plans; and Vulcans, a significant minority of people who behave rationally, gather data and vote with full information.”

“Unfortunately” he says “because of the dominance of hobbits and hooligans, democratic outcomes are not only not representative of the majority’s true views, but are also wrong and damaging to the common good.”

Given the youthfulness of our democracy and the diversity of it I would suggest that while it is obvious that we have a number of Hobbit and Hooligan voters in this country, we have more Vulcans than we suspect. These are the only people who are likely to change their vote based on the manifesto and the sloganeering of a prominent political parties. These are the only people who will interrogate the legitimacy of campaign promises.

Democracies around the world are like this, Winston Churchill was right!