A long journey

The journey by institutional investors to achieve better investor protections has been a long one. In November 2017, Futuregrowth (individually as well as part of ASISA FISC) embarked on a series of engagements with the JSE in order to effect changes to its Debt Listing Requirements (DLRs). These offered very little protection for investors, and we believed they needed significant improvement. New DLRs were eventually issued by the JSE on 31 July 2020.

While the new DLRs are an improvement on the previous version, we believe they still fall short in some key aspects.

When it became apparent that the JSE had back-tracked on its initial stance on including vital investor protections, Futuregrowth made written representations to the Financial Services Conduct Authority (FSCA) (as the regulatory entity responsible for oversight of the JSE) both individually and as part of the ASISA working group. Unfortunately, our requests for further engagements with the FSCA were denied, and the revised DLRs were issued without key investor protections. For some of the history of our engagements on this topic, please refer to the summary table and website links below.

Past engagements on bond market reform and standards

- 14 July 2017: Listings rules for issuers of debt ‘need to be tightened‘

- 24 Nov 2017: JSE debt-list rules fail SOE investors

- 21 Feb 2018: Highlights from our discussion on SOEs & the debt capital market

- 27 Feb 2018: Futuregrowth is tired of ‘ridiculous’ rules for bonds

- 7 Oct 2018: JSE proposals seek to tighten bond market listing rules

- 24 April 2019: The dangerous and murky shark tank of SAs listed bond market

- 24 June 2019: Are bond investors getting a raw deal again?

- 30 April 2020: Bond investors left out in the cold

- 25 Aug 2020: JSE debt listing requirements: Improvements are still missing

The journey continues

During our engagements with the JSE, they advised that they were unable to include certain protections (related to what they termed “commercial matters”) in the regulations and that these should rather be included in the underlying loan documentation.

In order to effectively address this – and to get a common view on the key protections and legal provisions required – the ASISA FISC agreed to form a smaller working group (with Futuregrowth as an active participant and contributor) to draft a set of “ASISA approved” Debt Listing Guidelines. The ASISA working group comprised representatives from ten institutional investors.

The guidelines formulated by this group were unanimously adopted by the ASISA FISC and were approved by the ASISA Board in March 2021. They can be viewed in full on the ASISA website. These guidelines will form the basis of Phase 2 of the drive for bond market reform by Futuregrowth and other institutional investors.

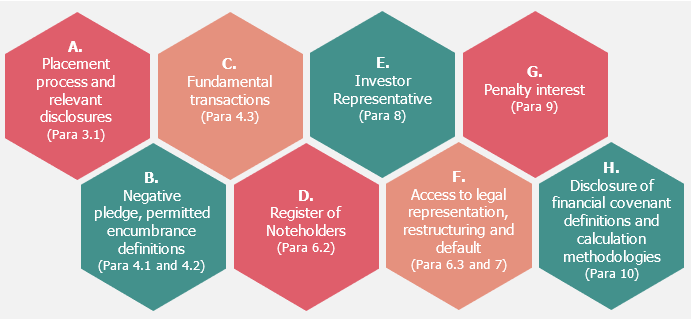

ASISA guidelines unpacked

We examine some of the proposed ASISA guidelines on loan documentation for listed instruments – and illustrate the rationale for these via examples from our own experience, where applicable.

A. Placement process and relevant disclosures (Para 3.1)

Why this is important: The method of pricing and placing bonds needs to be robust and fair. Auctions provide for price discovery and it is important for investors that issuers and their arrangers do not distort the market by either manipulating the quantity of bonds issued or the price.

Example: Let’s assume an issuer indicates that it intends issuing between R1 billion and R2 billion of a 3-year bond, at a price guidance of between 120 and 150 basis points (bps). If, at the time of the auction, there is demand for R2 billion of bonds, this demand would be filled at a spread of 150bps, whereas if the issuer issues R1 billion of bonds, the clearing spread would be 120bps. Possible market manipulation arises when the issuer issues R1 billion of the bonds at the clearing spread of 120bps and then, shortly after the auction, issues a further R1 billion in a “tap issue” or “private placement” at the same spread of 120bps. Had the issuer issued the full R2 billion at the time of the auction, the clearing spread would have been 150bps.

Proposal: To limit such manipulation by restricting an issuer from “tapping” an issue within a specific time frame of the initial auction – and requiring a detailed description of the placement methodology and required disclosures.

B. Negative pledge, permitted encumbrance definitions (Para 4.1 and 4.2)

Why this is important: To be effective, we believe that the wording of these clauses in issuer DMTNs needs to be amended in certain instances. Many DMTNs carve out “except in the ordinary course of business” from their negative pledge and permitted encumbrances, which nullifies the intent of such clauses as it means companies can encumber assets “in the ordinary course of business” which leaves a smaller pool of unsecured assets for lenders to have recourse to in a default scenario.

Proposal: The wording of these clauses needs to be considered so that the balance sheet that investors initially lend against is not allowed to be materially weakened during the term of the loan without some form of right or recourse. All forms of indebtedness should be considered, and wording should take into account the specific arrangements and circumstances concerned.

C. Fundamental transactions (Para 4.3)

Why this is important: There is a need for investor protection during restructures and unbundling transactions. Investors are required to take a long-term view on the lending of client money (which is society’s pension fund savings) and are currently without appropriate protections against degradation of the credit over the life of the loan.

Example: Eqstra, Imperial and Bidvest have all undergone corporate restructures while listed debt has been outstanding. The impact of these restructures, and the lack of protections outlined in b) above, meant that the balance sheets investors initially lent against (and had recourse to) changed materially, and investors had no right to either approve the transaction or negotiate better pricing for the increased risk.

Proposal: Asset disposals, mergers, amalgamations and corporate restructures, including internal restructures and unbundling transactions (“Fundamental Transactions”) should be restricted so that they do not materially weaken the balance sheet of the issuer and/or impact on the ability to service debt during the life of the bond.

D. Register of Noteholders (Para 6.2)

Why this is important: In situations like credit events, restructurings and defaults, where a speedy response is needed, and where the passage of time can and does result in a weakened position for investors (money can be drained from the company bank accounts, for example) unnecessary delays in investors’ ability to meet and make decisions are untenable.

Example: When Land Bank went into default in April 2020, it took nearly three weeks to collate the register of noteholders so that a noteholder meeting could be called. Investors faced similar difficulties previously when African Bank, PPC, Umgeni, CIG and Steinhoff had credit events.

Proposal: Issuers need to make available an up-to-date register of all their noteholders (that lists the legal owner as well as the name of the institution that manages the money) so that noteholders are in a position to meet and agree on the way forward.

E. Investor Representative (Para 8)

Why this is important: It is an established norm that in most syndicated loans, and certainly also in debt restructures, that a “bond trustee” or “facility agent” is appointed to perform the function of an investor representative. For this (often arduous) service, a bond trustee or facility agent would usually charge a fee which is – and should be – paid by the issuer, which is, after all, the party responsible for the default.

Example: One of the first things investors and Land Bank realised was essential after the Land Bank default, was the need for an Investor Representative to be appointed to enable an appropriate restructure negotiation with the wide body of noteholders and investors in Land Bank debt. Noteholders and Land Bank have been indebted to ASISA which was asked by Land Bank in April 2020 to act as an “Investor Rep” and to establish a Noteholder Committee. The role (for over a year now) has included coordinating and chairing Committee meetings, collating correspondence, responding to the myriad of investor questions, liaising with Land Bank and its advisors, sourcing and analysing the beneficial owners of the notes as well as tracing the institutional manager of each beneficial owner, and collating this data and providing it to Land Bank and the legal teams. The latter is a huge task, given that the legal owner of a note may not indicate the institution responsible for managing that exposure. Earlier this year, ASISA also engaged with the Land Bank Treasury team and its advisors on the partial capital buy-back process for Land Bank – which was complex and uncertain, and involved multiple parties including the noteholders, the JSE, the Central Securities Depository, as well as various administration teams and platforms. In the Land Bank restructure, we understand that ASISA is not being remunerated for the provision of these services. It must be noted that over 50% (by value) of the registered noteholders in Land Bank are not ASISA members. This implies that ASISA and its members are subsidising the non-ASISA members who are also benefiting from this work.

Proposal: The Land Bank example is an untenable situation that cannot be repeated. Hence, investors need to insist that DMTN documentation includes a provision for the appointment of an independent investor representative in the event of a default or restructure. As has been proven, this role is much more than just being a postbox, and the DMTN needs to provide for the costs of such an appointment to be borne by the defaulting issuer.

F. Access to legal representation, restructuring and default (Para 6.3 and 7)

Why this is important: In most other lending situations, the defaulting party is responsible for bearing the legal costs of the non-defaulting party, yet no such obligation exists in current DMTN programmes. There is a long list of DCM issuers who have not met their obligations, and where investors have been left with no mechanism to get appropriate legal advice that is paid for by the defaulting entity. We are currently in a bizarre situation where an issuer who has not met its previously agreed obligations is able to propose making changes to the agreed terms of the contract, with the investors having no way to require the issuer to pay for the legal costs associated with either the proposed changes or with navigating the restructuring or default.

Proposal: It is appropriate in the above circumstances that the party that has caused the change in agreed terms or that has not met its obligations (the issuer) should bear the legal costs borne by investors to deal with these. This is standard lending practice and one that investors should absolutely insist upon.

G. Penalty interest (Para 9)

Why this is important: Investors often neglect to ensure that default interest is “switched on” at the inception of a bond. If an entity defaults, the risk consequently increases; therefore, investors should insist that default interest is always switched on and that, when an entity has defaulted on its obligations, investors earn a higher return as compensation.

Example: In the Land Bank case, the notes did not require default interest, meaning that when Land Bank defaulted on its obligations, investors were not eligible to be paid an additional margin for the period that the bonds remained in default (what we call “default interest”).

Proposal: Usually default interest should be charged at an additional 200bps (2%) over the agreed interest rate, and would only apply when the issuer has defaulted on its obligations. This would go some way to compensate investors in a default situation. It makes no sense for investors to continue to agree to omitting this provision from loan documentation.

H. Disclosure of financial covenant definitions and calculation methodologies (Para 10)

Why this is important: Financial covenants set the limits to be adhered to during the life of the loan and are based on certain financial ratios. Investors need to be able to check that the calculations and methodologies used by issuers are within the agreed limits.

Example: We have had direct experience where the issuer has not made these available. In the example of Hyprop in previous years, investors disputed the basis for the Loan-to-Value covenant as calculated by the issuer when the appropriate disclosure by the issuer of their methodology was not forthcoming. Without a mechanism to resolve this dispute (such as the use of an independent calculation agent), it became difficult to assess the actual performance and take any necessary action to protect our client funds.

Proposal: The ASISA recommendations call for appropriate transparency and disclosure of covenants, which are key early warning signals for investors.

Activating Phase 2

We believe that issuers and investors need to work together to build an equitable DCM that protects both parties and that provides a fair platform for the buying and selling of listed debt instruments. The ASISA working group has considered both the practical implementation and possible impact on issuers – and has made every effort to produce a reasonable set of guidelines that will provide a fair set of protections while not being overly onerous on issuers. These guidelines arise from shortcomings in the current framework and the actual lived experience of investors, and we believe them to be equitable and rational.

Given the unanimous adoption of the guidelines by the ASISA FISC (which represents the overwhelming majority of investors in debt instruments issued in our DCM), we expect that these guidelines will become the new market standard over time. Futuregrowth has endorsed these standards and will be asking DCM issuers to incorporate them in their loan documentation going forward – with a reasonable passage of time for issuers to implement the recommended amendments to their existing DMTN Programmes. DM/BM

- Olga Constantatos. Photo: Supplied

This article was written by Olga Constantatos, Head of Credit & Nuraan Sulaiman, Investment Professional @ Futuregrowth

Futuregrowth Asset Management is a licensed discretionary financial services provider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.