Maverick Life

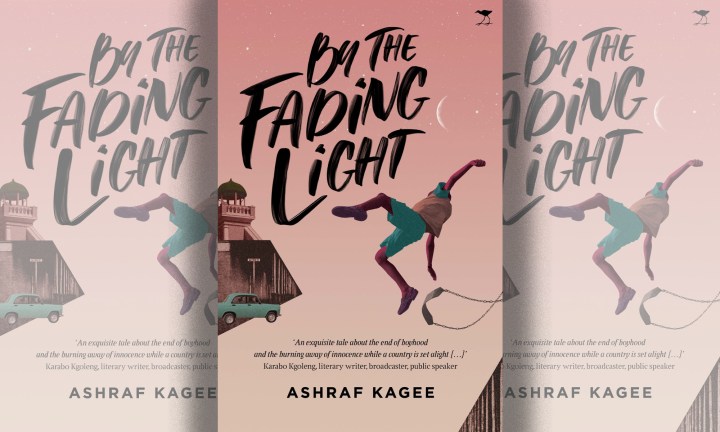

By the Fading Light – Bringing to life the texture of the time

Ashraf Kagee's book deals with the underlying issues of apartheid, class divisions and sexual violence; but it also has cadences of ‘lightness’ in that so much of it is told with astute humour.

It is the end of the afternoon, that sweet spot between day and night, when I connect with Ashraf Kagee on Zoom. An apt time for talking about his book, By the Fading Light. Kagee chose this time of day for the opening scene of the book, because it’s a ‘strange’ time.

“When twilight sets in and dusk comes, it’s sort of eerie. I wanted to use this ambience to create the sense that something sinister is about to happen,” he says.

The book tells the story of four boys, Amin, Haroun, Ainey and Cassius. Amin takes a different route home from school one day and is never seen again. The story covers the aftermath of his disappearance, how each of the boys grapples to make sense of the fact that Amin is gone. The book is part psychological thriller, part time-capsule, transporting the reader on a journey to life in Salt River, Cape Town, in the 1960s.

As a society, we draw on artistic forms to bring to life aspects of our history, where we come from, what has shaped us. By the Fading Light is not just a gripping story about Amin’s disappearance, it is also a way of commemorating aspects of both communal and personal memory.

“I was born in the 1960s,” says Kagee. “We lived in District Six until my family was forced to leave. I had family living in Woodstock and Salt River, so I have history in both these areas. These were the days when we took a bath using a bucket and a jug, the time of transistor radios and LPr (Long play records), so I recall the cultural artefacts of the era. My family often spoke about this time, so in some ways, I was recreating a fabric that I’d heard.”

Kagee, with deft skill, stitches this fabric together, bringing to life the texture of the time — the sights, the sounds, the folklore. It transported me to the stories my own family would tell about life before the forced removals that came with the Group Areas Act. The book felt deeply nostalgic, a trip down memory lane, one that conjured up the voices of those who came before. The words dance off the page to recreate the anticipation of going to the Palace Bioscope in Woodstock, the music, the sense of community.

“This was a time when there was an element of social capital, of densely trafficked networks where people knew each other and there was kind of a thickness about it, something that was lost when people moved out after the Group Areas Act,” says Kagee.

When Kagee began work on the book, he wanted to tell a story through the lens of young children. “The moment of late childhood, just before adolescence, is a special developmental time for young boys. There is some insight into the ways of the world, while not quite understanding and grasping things. I wanted to capture that.”

The book is a coming of age story, about the loss of innocence. It takes us into the inner challenges of young boys who are trying to navigate their way through difficulty.

“One would think that the adults around them would take care of them, have their best interests at heart. At a certain level they do, but the adults are also consumed with their own grief and trauma. This makes them oblivious to the internal worlds of the boys, the ways in which they are struggling.”

While the story is sad in many ways, I cannot emphasise how funny it is. Kagee is adept at making us laugh. Humour is sometimes used to navigate through politically tense situations, such as in the case of Cassius’ mother, Octavia February. Octavia is desperate to eviscerate her past. With her fair skin, straight hair, and sharp nose, she tries to officially reclassify her family as white:

“Octavia and her daughter, Cordelia, had passed the race test with flying colours; but not Cassius. The thing of it was — his hair. It was somewhat…. well, curly, kinky, some would say kroes. He’d passed the first tests the dour grey-suited official, Mr Malan, had put him through at the Department: pigmentation of the skin — even if it wasn’t exactly a pinkish hue; shape of the nose — even if it wasn’t exactly long and pointed; eye colour — even if it wasn’t exactly Atlantic blue. But, when Cassius was submitted to the pencil test, he failed it…… Sadly, dismally, rottenly, the pencil had gotten stuck in his kinky curls and refused to budge. Life turns on a dime, they say, or in this case on a pencil that stubbornly defied gravity.”

While the book has cadences of ‘lightness’ in that so much of it is told with astute humour, it deals with the underlying issues of apartheid, class divisions and sexual violence.

“If you’re a writer in South Africa, it is impossible to tell any sort of story without acknowledging the political context within which the story is located. Apartheid seeps into our lives and has always done so. I am unable to tell a story in South Africa without at least giving a nod to the political context. Having said that, I didn’t really want to tell a political story because there are so many of those. And other writers can do it better than me,” says Kagee.

Yet, Kagee does exceptionally well at, for example, dealing with ‘false consciousness,’ when those who have been colonised want to become like the coloniser and, in so doing, reject their own context and background. This is illustrated with Octavia February who wants to speak with a quasi-British accent, irons her hair straight, and decorates her home with all the trappings of the coloniser (a picture of Queen Elizabeth and other European artefacts bought on the Grand Parade).

While the book deals with the loss of innocence on the part of the boys, it parallels this with the loss of political innocence. “The 1960s heralded the end of the passive resistance movement. If you think about this time after the Rivonia trial, on the surface nothing happened, South Africa was relatively peaceful. It was only in the late 1960s and early 1970s that the Black Consciousness Movement became galvanised. But if you scratched underneath that surface, you saw the repression, the security police, and the brutal suppression.”

Kagee weaves the thread of counterfactual thinking, a concept in psychology, into the story. This is the human tendency to create alternative scenarios to events that have already unfolded. When we confront loss, or the sense that things are not quite right, we tend to want to reverse time and construct alternative realities — the notion of ‘If only I had done this one thing differently, I could have averted that outcome.’

This device is used in the sub-narratives of each of the families of the boys, the boding sense of pain and suffering that could potentially have been averted. By the Fading Light is written with such skill, with such insight into human consciousness. It will make you laugh out loud and make you want to step into the pages and give the characters a hug. It will also stay with you a long time after you are done with it. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.