BOOK REVIEW

Raiding the state armoury: Ordinary South Africans were victims of the conspiracy to sell police guns to criminals

The 1,066 fatalities on the Cape Flats between 2010 and 2016, and which can be linked to the illegal sale of guns from the police armoury by a former brigadier, amounted to ‘the deadliest single crime to have been committed in post-apartheid South Africa’.

Researching the devastating effects of a criminal class that has effectively been armed with state weapons, Mark Shaw, director of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, interviewed over 200 gangsters, cops, gun dealers, lawyers and experts over a period of three years.

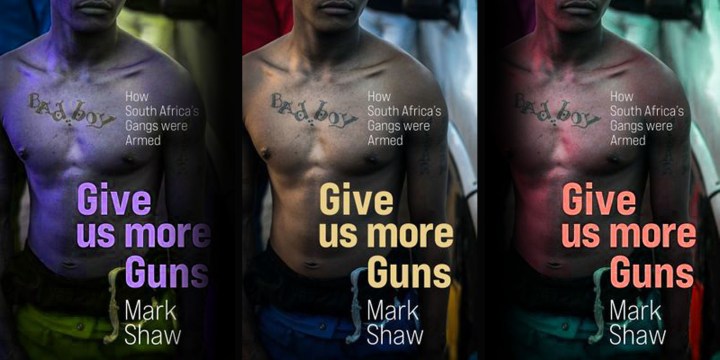

The result is Shaw’s second book, Give Us More Guns, a disturbing deep dive into how easy access to guns and the state armoury has altered the nature of crime, escalating ongoing internecine warfare between criminal rivals looking to expand markets.

These state weapons have fuelled violent conflict in the KwaZulu-Natal taxi industry where private security companies, armed with state weapons, protect powerful commercial and political interests.

They have empowered cash-in-transit syndicates, extortion rackets and low-ranking gang members.

And because the most popular gun on the black market is the South African-made Z88, known as The Zulu, criminals now carry the same guns as the cops as a mark of equality; of a level playing field.

Investigating the links between corrupt cops and the underworld has exacted a terrible price, including the assassination of Anti-Gang Unit detective Charl Kinnear. Kinnear was investigating his colleagues.

It can also be evidenced in the growing body count at mortuaries, mostly of young men felled by bullets. In gangland, the knife has been rendered redundant.

“The story of the killing can’t be told without understanding the source of the firearms; the police armoury,” writes Shaw.

With government-issue guns as accessible as a box of Smarties, young gang members and new gangs have begun violently to muscle in on historical gangland borders, seeking quick and nasty profits.

He who has a gun has power, and the around 9,000 such weapons which were illegally funnelled to the criminal underworld – some of them stockpiled – remain a grave threat to the country’s national security and our fledgeling democracy.

While ordinary people experienced gangs in highly localised ways, Shaw found that “the threads that tie together the supplies of drugs and violence span the country”.

“The connections between gangsterism in Cape Town, parts of Johannesburg and Nelson Mandela Bay, as well as Durban – long a trafficking hub – are closely knit.”

Give Us More Guns is a sobering read and a devastating indictment of the politicisation of law enforcement, particularly during Jacob Zuma’s term as president.

The man who opened the door for these vectors of death to be spread far and wide is a disgruntled former apartheid-era senior policeman by the name of Brigadier Christiaan Lodewyk Prinsloo. He did this to secure his retirement and his children’s education after being passed up for promotion.

Prinsloo was sentenced to 18 years in jail but was recently released on parole. He has turned state witness and his evidence is expected to blow open deeply rooted networks of criminals within the ranks of the SAPS.

The number of fatalities linked to Prinsloo’s decision to sell weapons from the police armoury to criminals totalled 1,066, with 1,403 attempted murders between 2010 and 2016.

“These numbers of killings mean that Prinsloo’s work is without doubt, the deadliest single crime to have been committed in post-apartheid South Africa,” writes Shaw.

“What interview after interview with gangsters has revealed is that the Prinsloo guns transformed the nature of organised crime and ordinary people are living with the consequences.”

Cape Town, where most of the Prinsloo guns were circulated, was now “one of the most violent places on earth”, writes Shaw.

It is something very hard to get your head around; the police and the wider state, both wittingly and unwittingly, armed criminals in South Africa, strengthening their operations and activities by giving them access to firearms, and threatening the life opportunities of many ordinary people.

This flooding of communities with guns resulted in “an orgy of killing so intense that in mid-2019, the South African military were called to patrol the city’s gang-infested areas”.

“It is something very hard to get your head around; the police and the wider state, both wittingly and unwittingly, armed criminals in South Africa, strengthening their operations and activities by giving them access to firearms, and threatening the life opportunities of many ordinary people.”

It is almost expected that today, state-issued guns and ammunition turn up linked to crime scenes.

Shaw writes that the response of the police as a whole “is a sobering indictment of the politicisation of law enforcement and its eventual breakdown during the Zuma presidency”.

Much has been written about State Capture, says Shaw, but the story of the leakage of guns from the state “deserves to be seen as part of the State Capture scandal”.

“It is without a doubt a reflection of the wider process of institutional breakdown that began before the Zuma administration, but was accelerated by it.

“It is the result of corruption, poor management, incompetence and arrogance on the part of state officials, defying the imagination in the same way that the various threads of the State Capture story have continued to shock South Africa.”

How Prinsloo and Naidoo’s network – using an intermediary, Vereeniging businessman, Irshaad ‘Hunter’ Laher – would come to be exposed by an astute cop, and how the investigation would later be run by Major General Jeremey Vearey and Peter Jacobs, makes for page-turning reading.

It would be a great crime thriller were it not for the real-time devastation of addiction, violence and murder Prinsloo’s actions unleashed in communities held hostage by powerful and seemingly untouchable crime bosses.

It was a Manenberg police constable, Lutfie Eksteen, who first picked up the pattern while working as part of Operation Combat, led by Vearey. Operation Combat, launched in 2012, was aimed at taking down gang leaders.

This resulted in the conviction of George “Geweld” Thomas, “a hardcore boss of the 28s”, for what Shaw terms “the most unspeakable acts of violence”.

Luftie picked up in 2013 that large volumes of police guns had been flooding into the Western Cape. Eksteen called Vearey directly. He had been close to the general and trusted him.

Court documents have subsequently revealed that Prinsloo had been selling guns since 2010 but that no one had really taken notice.

“The most likely explanation for the time lag is that crime intelligence information gathering and analytical capacities had declined to such an extent that either the system had failed to collect crucial information or the pieces were simply not put together higher up the chain,” writes Shaw.

The story of the people behind the guns investigation, writes Shaw, “says a lot about the way policing in South Africa now works – or perhaps has always worked”.

At the 2013 stage of the investigations, the scale of it was “not immediately clear to the small group of cops in the know”.

Those cops included Vearey and Peter Jacobs, who was deputy provincial commissioner for the Western Cape at the time, Clive Ontong and others. The investigation was dubbed “Operation Impi”.

Both Vearey and Jacobs were targeted for removal soon after Jacob Zuma made key appointments to the leadership of SAPS and the DPCI in 2016. Khomotso Phahlane was appointed acting commissioner and Berning Ntlemeza was appointed to head the Hawks.

Shaw suggests an independent inquiry be held into the number of weapons lost by SAPS. There should also be an independent audit of the firearm destruction process as “the public have the right to be assured that the firearms are in fact destroyed”.

In Cape Town, Phahlane appointed Kombinkosi Jula as provincial commissioner and Mzwandile Tiyo to head Crime Intelligence. Jacobs was unlawfully shafted from this position and later won his labour court challenge.

In 2016, gangland lawyer, Noordien Hassan, was assassinated – a tipping point for the underworld.

Hassan, writes Shaw, “was the spider in the web, the centre of a network of communications, the holder of critical purse strings, the indirect facilitator of the flows of drugs and guns – even if his work never seemed to touch either directly”.

Hassan also represented Laher, Prinsloo’s go-between.

From the start, Vearey and Jacobs had kept the operation close to their chests and by 2014 ballistics tests that had been performed on seized weapons pointed to the armoury.

“The whole operation to trace the guns remained secret. Ontong, in a sworn statement, later recounted that the operation had been enacted ‘in a covert manner because of the sensitivity of the case being investigated’,” writes Shaw.

Operation Impi’s investigations led them to KZN where “the shit hit the fan”. Shaw details how Vearey and Jacobs began to get too close to powerful KZN taxi bosses, their private militias armed to the teeth with police weapons and their political connections.

Shaw ends his book with the thought that the Prinsloo case “was enabled by the sorry state of affairs in South Africa’s gun control regime”.

“The Prinsloo story is but one case that has undermined trust in the state, and it raises worrying questions about the ability of South Africa’s police service to safely and securely manage and control firearms – and to keep them out of the hands of violent criminals.”

Remarkably, he adds, there have been “no consequences” for SAPS management – “no accountability, no responsibility taken, and certainly no public apology. These are overdue.”

Shaw suggests an independent inquiry be held into the number of weapons lost by SAPS. There should also be an independent audit of the firearm destruction process as “the public have the right to be assured that the firearms are in fact destroyed”.

The role of private security companies also “requires urgent attention”.

“Private security companies should not be allowed to become militia-style groups for the industry. We are heading for more violent and virulent forms of organised crime in the taxi industry unless the state acts firmly.”

By failing to stem the flow of firearms “from its own strongrooms”, writes Shaw, “the South African state has triggered significant changes in the country’s criminal economy.

“Ordinary citizens have paid the price.” DM

Register here to join Marianne Thamm in conversation with Mark Shaw for the virtual book launch of Give Us More Guns: How South Africa’s Gangs Were Armed.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.