DM168

An intimate gaze: Ruth Motau on documenting life in black and white

The legendary South African photographer reflects on her career and the stories and people behind her images.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

Ruth Motau’s black and white images have not only become iconic and important emblems of South Africa’s photographic history, they also capture life, at once raw, powerful, solar, dark and empathetic in intimate essays.

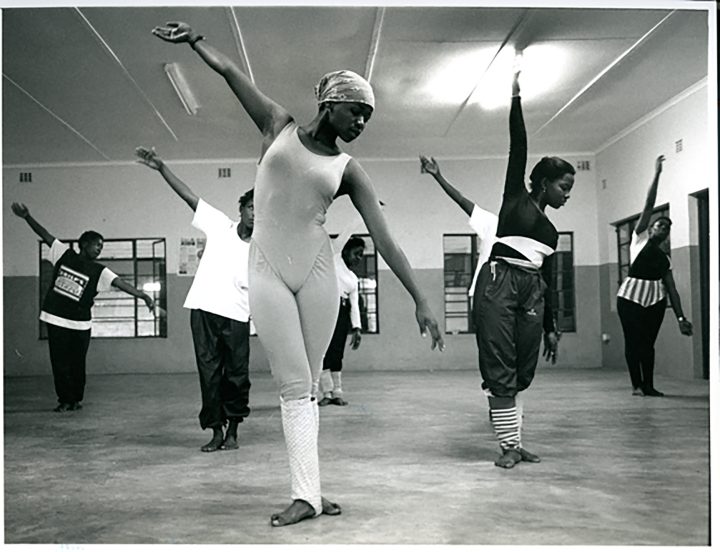

From dancers at a Soweto dance class, caught in movement, arms lifted, energy bursting through the image, to patrons drinking beer in shebeens, the overall rolled down to the waist or Toni Morrison, her face beaming in a ray of sunshine, Motau’s gaze is concerned; she takes time to tell a story. The photographs – and the photographer – are never rushed. Shooting demands thinking, preparation, conversations and engagement with ‘the other’ — the person or place being photographed — that goes beyond the click of a shutter.

“For me photography, is about thinking, conceptualising your story. (Today) going out there, documenting life, I think it’s completely different to whatever it was before… I think there’s still a few of us who sit and then think about projects and think about what you’re going to do, what kind of stories you want to do, what message you want to portray. Or, you know, tell the people what you want to do, or what you want to achieve,” she says.

She calls it the difference between “accidental photography” and “real photography”, between collecting images as knee-jerk reactions to life and one’s environment and the news, and immersing oneself in visual documentation. Both are complementary but not always similar.

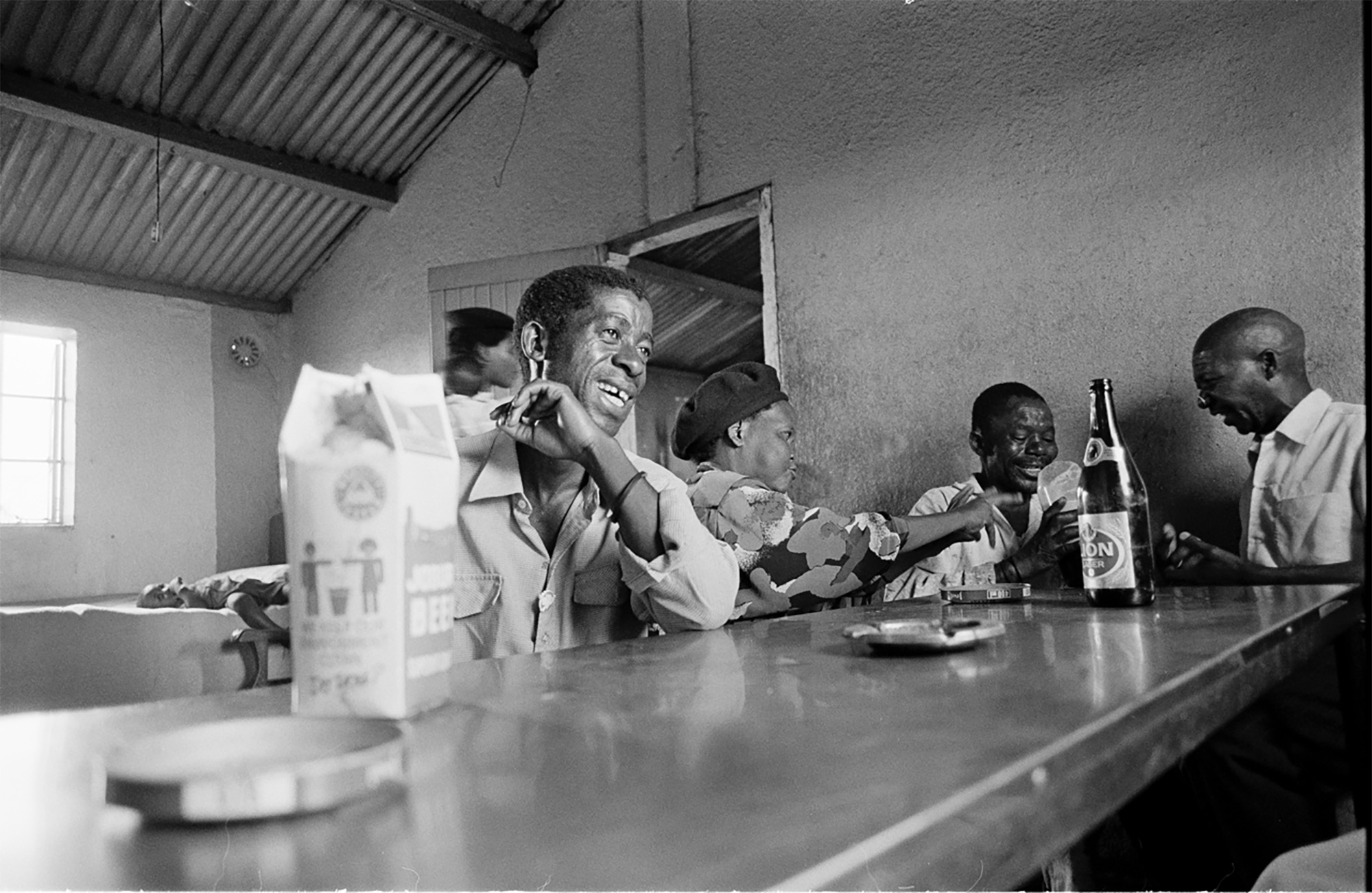

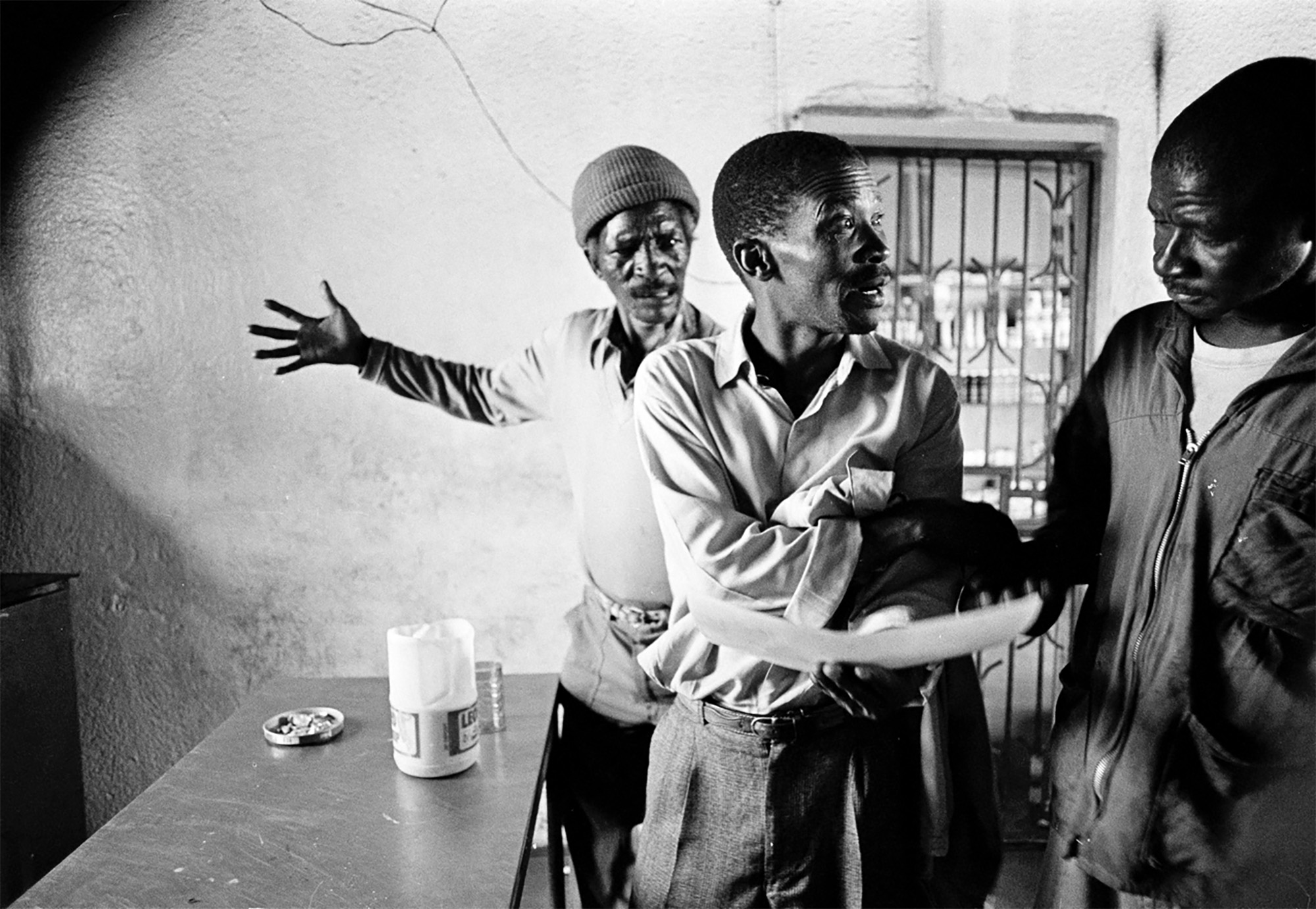

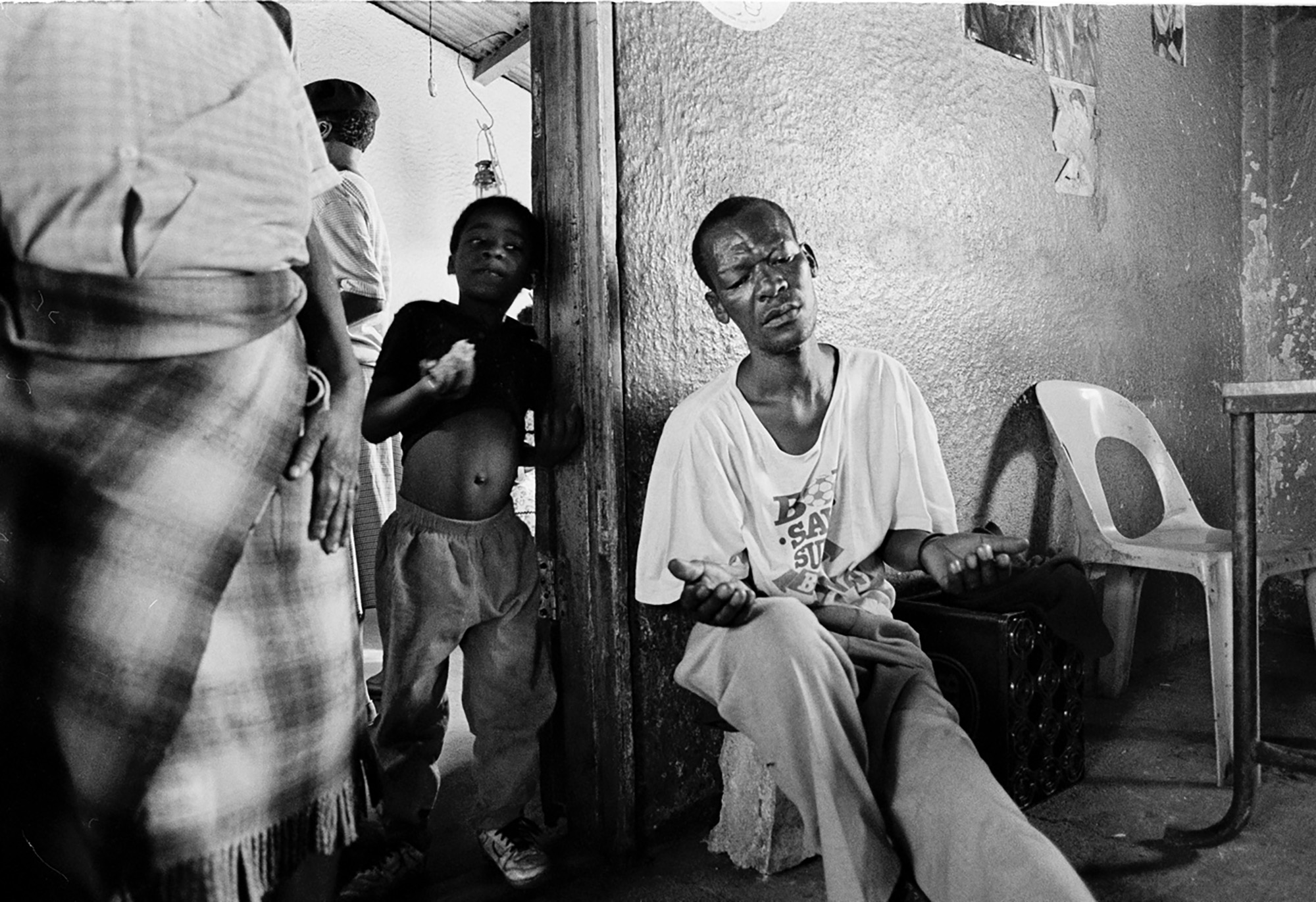

“When I go, (to) the shebeens, I knew about what (was) going on in the shebeens… I went for the first time, I took … few shots. I went for the second time, but then I knew exactly what I was going to get. Because I looked around at the situation, the environment, the kind of people who go there… So it was kind of easy when I went for the second time because I already knew what I (was) going to get…”, she explains.

A shebeen in Dobsonville; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

A shebeen in Dobsonville; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

Men in a shebeen in Dobsonville; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

A shebeen in Dobsonville; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

Growing up, Motau knew she “always wanted to do things”.

“I knew that I was not going to work in an office. I’ve always been very creative… I think music has always been one of my passions… if I wasn’t a photographer, I think I would have been a musician, funny enough. I’ve always been artistic, and I knew that I was going to be an artist.”

Born in 1968 in Meadowlands, Soweto, Motau remembers that when she asked her parents for a camera — the support she received from her father was absolute.

“I was my dad’s favourite. When asking for a camera, he never hesitated, he never asked me why or whatever. He just bought it for me. And I thank him for that. Because I’m thinking if he didn’t… where would I have been?”

But he did and Motau went on not only to become a legendary photographer, but also the first black woman photographer to hold the position of photo-editor, at Mail and Guardian, only a year after the first democratic presidential elections.

Since then, she hasn’t stopped photographing – and still does today, approaching each project, and the people she captures with her camera, with careful attention and respect.

“I think my relationship with the people I photograph… it’s very important. And before I photograph them, I ask for permission. It doesn’t matter whether you are a president, or whether you are wealthy or you are poor, I always ask for permission. If a person says no, I respect that.

Pensioner smokes a pipe, Soweto; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

Pensioners in the queue, Soweto; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

Pensioners, queue 2, Soweto; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

Pensioners, queue 3, Soweto; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

“And for me, it really doesn’t matter. Because without that person, I cannot tell a story. So permission is key. Saying yes, it gives me freedom to do what I want to do and express myself. But if somebody says no, then it doesn’t give me (that) freedom and I (would) be stealing some of the images… Agreeing is opening a door to come in. I think also, when somebody invites you in, you (shouldn’t) abuse it; you have to respect it,” she says.

Motau’s photography is reminiscent of the black and white pictures from the 30s and the 40s, at times echoing Dorothea Lange’s social documentary photography – who, like Motau, would effortlessly go from portraiture to photodocumentary. It may also be compared with the work of American photographer, writer and film director Gordon Parks. Curator and author Philip Brookman, in a text dubbed, “Unlocked Doors: Gordon Parks at the Crossroads,” published in Gordon Parks: Half Past Autumn, noted: “A photographer can be a storyteller. Images of experience captured on film, when put together like words, can weave tales of feeling and emotion as bold as literature.… (Photographers) bring together fact and fiction, experience, imagination, and feelings in a visual dialogue that has enormous impact on how we observe and relate to the external world and our internal selves.”

That visual dialogue permeates Motau’s work; the images have a degree of intimacy that sometimes happen after moments spent sitting with people and exploring the story captured. She feels the story, pieces it together so that when the images are developed, they too, bring together “experience, imagination and feelings”.

“If I have to tell a story… You go in there, you sit, you drink, you dance, then you talk… ” she says.

Meadowlands dance group rehearsing at the Bapedi hall; Photograph by Ruth Motau (Courtesy of Ruth Motau)

“You can talk to people and say this is how I want to do it… You need to humble yourself… And if somebody says, no, it’s no. And sometimes take those pictures back and say, here are your photographs,” she adds.

Respect for the subjects photographed comes from humility, something she experienced when working with late former president Nelson Mandela. “I remember, and I can’t remember which year it was, but I was invited to be Mandela’s official photographer, and we went to Sharpeville… he was a very humble human being… And he would always introduce himself, ‘I’m Nelson’… Everybody knew him. But he would always, always introduce himself. And for me… It doesn’t matter who you are. I would meet Nelson Mandela now or meet Bill Clinton now, and then, the next minute I meet a homeless person. For me, it’s the same, it’s the same respect that I’ll give them.”

More recently, she’s embarked on a spiritual journey, while documenting churches, sangomas and other people’s spirituality. “I think I’ve been doing (a) spiritual journey, especially in black communities. (I found) people’s spiritual journeys so different; and how people relate to spirituality, it’s all so different. And along the journey, I have learned that we are spirit beings. Your soul, what you feed your soul with, or what it is that you feed yourself inside, it’s more important than the outside.”

Reflecting on her career, and looking back at the many places and people she photographed, Motau sighs and adds with a smile: “I think what I’ve done is what I wanted to do. And there’s nothing that I think I haven’t done. But I would like to go back and revisit some of the places that I have covered before. And then see how they are… and then retell the story again.” DM/ ML

Ruth Motau is a member of the Photography Legacy Project and the African Photojournalism Database, a project of the World Press Photo Foundation, as well as a member of Black Women Photographers.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.