MATTERS OF OBSESSION

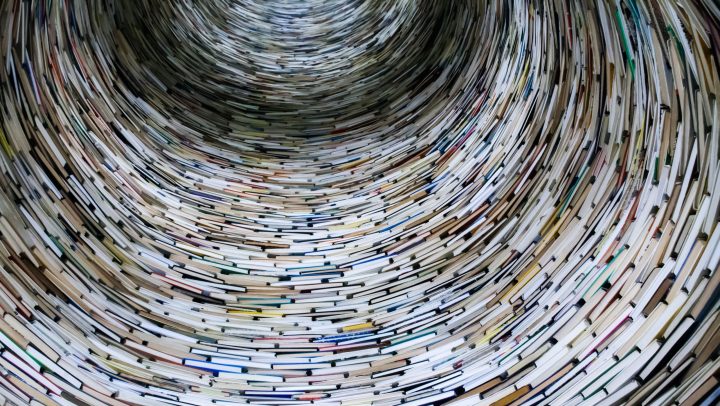

Remembering the stories of us: Preserving our linguistic heritage

Recording, collecting and archiving our stories, languages and histories is a constant work in progress that requires immense manpower and resources. The first step, however, is recognising the worth of our heritage.

The Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wrote in 1986 in Decolonising the Mind that, “Language carries culture, and culture carries, particularly through orature and literature, the entire body of values by which we come to perceive ourselves and our place in the world… Language is thus inseparable from ourselves as a community of human beings with a specific form and character, a specific history, a specific relationship to the world.”

In South Africa, the role of language has always been a powerful one. In 1976, the Soweto Uprising was sparked by the forced imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in Soweto schools. When our new Constitution was enacted it contained 11 official languages, as well as a section that states: “Recognising the historically diminished use and status of the indigenous languages of our people, the state must take practical and positive measures to elevate the status and advance the use of these languages.”

However, this has not always been as successful in practice as in theory. As Constitutional Court Judge Johan Froneman admitted in a 2019 judgment concerning the constitutionality of Stellenbosch University’s revised language policy: “The flood-tide of English risks jeopardising the precious value of our entire indigenous linguistic heritage… This is because the march of history both in South Africa and globally seems relentlessly hostile to minority languages.”

The fight to preserve our stories, languages and histories was bound to be tough in a sociopolitical environment that leaves little energy or funding for activities not tied to the day-t0-day survival of South Africa’s citizens.

Examples of institutions dedicated to preserving our heritage that are struggling to survive abound: including the almost 200-year-old Lovedale Press in Alice in the Eastern Cape. The press produced and published some of the most influential African intellectuals in the country, including the first black author to write a novel in English, Sol Plaatje, the dramatist HIE Dhlomo and one of the few women who were published at the time, Victoria Swaartbooi.

The press has, as Emilie Gambade writes, “survived a war, apartheid, threats of closing down, an auction, more threats and the slow-burning disappearance of the printing world”. It was once more on the verge of closing until visual artist Athi-Patra Ruga and voice artist, actor and academic Lesoko Seabe launched a project called Victory of the Word in the hope of saving the press. The project, which was initially “a three-phase fundraising and development project” to draw attention to and support the press and its custodians”, goes beyond raising money – it’s designed to save the cultural institution and strengthen the role it plays in archiving our heritage.

An institution in an equally precarious situation is the Liliesleaf Farm Museum in Johannesburg, where the Communist Party of South Africa had its headquarters in the 1960s; it is also where the then-banned ANC held its underground meetings and where, among others, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba and Ahmed Kathrada were arrested.

The museum also contains an Archive Research Site, where the various deposits of unique records of the liberation struggle are preserved and digitised, an effort also threatened by the museum’s lack of funding. “We have such an important role to play – to be the voice of our past by highlighting the brightness of what our struggles symbolise… what we were trying to achieve, it is a continuation of the voices that have now passed into history,” Nicholas Wolpe, the CEO of Liliesleaf, told Daily Maverick’s Suné Payne.

On reaching the conclusion that preserving languages and the written word is vital, the question is: How does one archive written work?

Archiving our heritage

Dr Sandra Shell worked at Rhodes University’s Cory Library for Historical Research for 30 years and processed the Lovedale Press archives there. She explains the process of archiving, with particular reference to her work with the Lovedale Press.

“In the case of the Lovedale records there were two distinct deposits: the first deposit of the records of the Lovedale Mission and the Lovedale Institution… arrived in Cory in 1961… The Lovedale Press archives were deposited in Cory during 1976, with additional but smaller deposits arriving in subsequent years.

“The processing of these institutional and press archives required in-depth reading and immersion in the topic of each item or cluster of items to give researchers a clear idea of what the cataloguing unit comprised, and its context”, she says. In addition, “the physical condition of the paper documents frequently needed conservation and preservation interventions through thorough cleaning and removal of rusting fasteners. Folded pages needed smoothing and flattening. Signs of active mould or living insect infestation meant fumigation to prevent the spread of spores and insect damage. Then the allocation of a unique call number created by the library’s accession register. Finally, the clusters of pages were placed in labelled folders and file boxes.”

“The physical documents and other materials in their labelled boxes are, in the case of the Lovedale deposits, on shelves in the appropriate fire-protected strongrooms at Cory [Library].”

Before Covid-19 these records were accessible to staff and students at Rhodes University as well as all bona fide external and visiting researchers. When the records were deposited one of the conditions was that it should be “made accessible to bona fide research students of any race group”.

However, there are many deposits that are destroyed or damaged, never to reach archival shelves. Some of the collections at Lovedale Press almost suffered a similar fate, explains Shell.

“One year in the 1980s or early 90s… the Lovedale Press reported a major fire in their basement store, which destroyed a sizeable number of books and manuscripts. Staff from the Cory Library drove directly to Lovedale and waded through the basement where a substantial amount of material had survived the fire but had then been doused by the fire hoses… We had a Kombi and were able to pack it to the brim with rescued items.

“Armed with all the blotting paper we could find in Makhanda and with plenty of fans, we unpacked the contents of the Kombi into my house. I emptied my freezer of its contents and replaced it with the worst and the wettest packages of paper to arrest further deterioration. I set up the fans and covered every possible flat surface on which to fan the pages with blotting paper dividers and directed the fans as evenly as possible. We were desperate to save these valuable products of the historic Lovedale Press and it was a race against time. While we lost some items due to irreparable damage, we were able to rescue a large proportion and, once completely dry, these were processed and absorbed into the collection.”

Stories such as these abound and demonstrate the inherent vulnerability of working with original manuscripts. However, the modern shift toward digital archives is helping to ease the burden on archival centres to safeguard originals.

How can we better archive our history?

Shell suggests there are three main ways we can better preserve the South African languages and written word. “The first would be to ensure as much detail as possible concerning existing collections is disseminated via digitisation… There must be a democratisation of these invaluable records to benefit the largest number of people through the digital… Digitisation of records, especially of fragile materials, takes a great deal of careful time and a great deal of funding, which are in short supply where institutions are running on a skeleton staff and ever-tightening institutional budgets.

“The second would be to encourage communities to search actively for caches of unpublished manuscripts in any of South Africa’s official languages, including the Khoe and San languages, that are in private hands. This can be a highly sensitive exercise where communities feel, correctly, that there needs to be community buy-in to avoid any sense of exploitation by institutions… approaching the community, offering to digitise a copy for the repository to archive is one way to ensure the owners of the documents retain the original while allowing access to the item in digital format.

“The third would be to encourage and include the collection of oral interviews in the vernacular. A number of repositories have been doing this for many decades. There are distinct advantages to the dissemination of recorded and transcribed content as well as to preserving for posterity to demonstrate how a language was spoken.”

All this would, little by little, help preserve our languages and written word. As Judge Johan Froneman wrote in the Constitutional Court judgment: “Without your own language, culture is lost, a sense of self is lost. And once that happens, diversity is lost… The point of this is that the Constitution enables each one of us to be proud of our language. We need not destroy one language to advance others.” DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.