OP-ED

Zambia debt crisis just the ears of the hippopotamus in Africa’s perilous fiscal position

Zambia’s debt crisis is part of a much bigger affliction facing many sub-Saharan African countries which have been sinking in sovereign debt since the financial crisis of 2008. Persistent systemic governance and economic challenges accompanied by external shocks have led to a rise in the continent’s indebtedness.

Even in the less superstitious view, Friday the 13th is an unlucky day. In the African sovereign finance world, Friday 13 November 2020 will be remembered as the day in which one of the member states, Zambia, failed to meet its debt servicing commitments of $225-million due to the country’s lenders.

It is tempting to ascribe the country’s failure to meet its debt obligations to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, Zambia and many Africa watchers have seen this coming. A recent seminar held by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and the Brenthurst Foundation shed more light on Zambia’s path to chronic indebtedness under President Edgar Lungu.

However, focusing on the Zambia debt crisis in isolation would be remiss. It is part of a much bigger affliction facing many of the sub-Saharan African countries. African countries have been sinking in sovereign debt since the financial crisis of 2008. Zambia illustrates some of the fiscal challenges the continent has been facing. Some of the systemic issues around African debt include low domestic savings, low or non-existent revenue collection, exchange rate volatility, illicit financial flows, base erosion and profit shifting, and outright corruption.

Zambia gained independence from Britain in 1964. That period ushered in a one-party state led by Kenneth Kaunda. After almost 30 years, Zambia adopted multiparty democracy with the then-incumbent Unip losing power. The Kaunda era was characterised by mass nationalisations and socialist experimentation that almost collapsed the economy. However, the introduction of democracy led to privatisation, a free-market economy and building of democratic institutions. Since then Zambia has been doing relatively well by regional standards.

Zambia’s current economic meltdown can be traced to the change of government in 2011. The situation has got much worse since the coming to power in 2015 of President Lungu, who has displayed an authoritarian streak coupled with allegations of financial mismanagement.

Another major development under Lungu has been considerable involvement of the Chinese as lenders and players in the country’s infrastructure space.

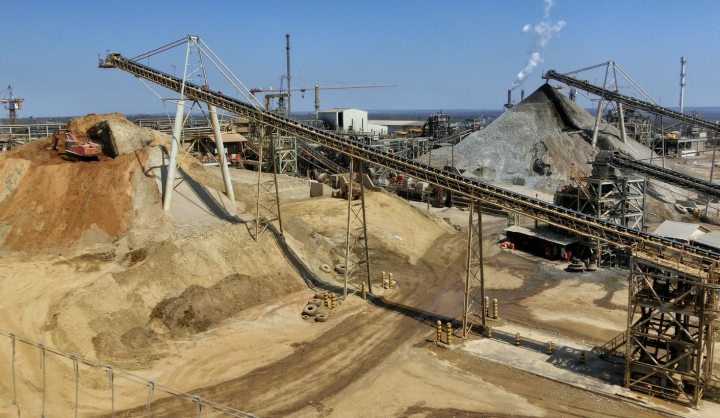

Zambia’s economy is dependent on mining, mainly copper, with the country being the second-largest producer of the metal in Africa. The reliance on minerals has in a way led to the Dutch disease. The country’s debt-to-GDP stands at 100%, having risen from 60% in 2017. The debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to continue rising as the country faces low economic growth. Zambia’s default on the EU bond-holders commitments on 13 November will spell further difficulties for the country’s fiscal and borrowing standing.

It is difficult to get a precise figure on how much Zambia actually owes. This is because the country’s debt is mostly owed to commercial banks. Over and above that, Zambia owes a lot of money to Chinese private entities. It is common knowledge that most of the Chinese private lenders are in essence controlled by the state. So far the Zambian government has admitted to owing $7-billion in sovereign debt to both internal and external creditors.

However, some analysts have suggested that the total sovereign and non-sovereign debt owed by Zambia lies somewhere between $18-billion and $24-billion. Zambia sits on only $1.4-billion of international reserves, enough to cover imports for two months. This is compared with neighbouring Botswana, that has enough international reserves to cover 15 months of imports.

There is much secrecy around the exact figure due to the nature of Chinese entities’ lending practices which have had an impact on Zambia’s access to IMF liquidity. The Zambian authorities have approached the multilateral finance institutions for funds, however, the IMF and World Bank have specifically rejected Zambia’s requests for loans. These bodies argue that Zambia must declare all its debt before any financial lifeline can be extended to the country. Zambia is at a point that it could be forced to use IMF loans to repay Chinese debt: a classic case of a debt trap, borrowing from Peter to pay Paul.

The African debt situation is almost akin to the 1990s debt crisis, with a few nuances that distinguish the two eras.

At a macro-economic level, the mining industry has suffered from the Lungu administration’s excesses. Mining companies are not getting their VAT refunds. This threatens their livelihoods, coupled with interference from the state. Global mining giant Glencore has recently announced that it may divest from Zambia. The government has, in turn, promised to buy a 90% equity stake, effectively nationalising the copper mining industry; this in a country that went on to its knees due to post-colonial resource nationalism that gripped African countries from the 1960s to early 1990s.

However, it is important to note that Zambia presents a mirror of the African debt situation, albeit an extreme one. In the region, Mozambique has found itself embroiled in a scandal in which a $2-billion debt was hidden from the IMF and World Bank. The money had been siphoned into different accounts privately held by senior political leaders. Mozambique’s debt scandal sucked in Swiss bank officials and included former finance minister Manuel Chang who remains holed up in a South African prison fighting deportation to the US.

The African debt situation is almost akin to the 1990s debt crisis, with a few nuances that distinguish the two eras. In the 90s, the Paris Club of creditor countries forgave the debt of 36 Highly Indebted Countries. Out of these, 29 were African countries. The debt amnesty was always seen as carrying a risk that the beneficiaries may find themselves in a similar situation due to lack of consequence management. It was thought that improving governance and fiscal discipline would avert any future debt crisis.

While coups, wars and famine have gone down since the turn of the millennium, phrases such as “Africa rising” have been used to describe the continent. However, persistent systemic governance and economic challenges accompanied by external shocks have led to a rise in the continent’s indebtedness. There are three main external factors influencing African countries such as Zambia into finding themselves in a debt trap. These include the 2008 financial crisis, trade shocks linked to a fluctuation in commodity prices and, ironically, access to a wider range of lenders, mostly outside the traditional lenders.

The Paris Club and international financial institutions such as the World Bank and IMF could attach governance-related conditions to their loans, loans which were offered at lower-than-commercial interest rates. Now, African countries have access to commercial debt that attracts very high interest rates. Servicing the interest on the loans can consume as much as 90% of a country’s annual revenues.

Some of the internal factors that have led to the debt crisis in Africa, including Zambia, relate to having low tax revenue and illicit financial flows. Unctad, Uneca and the Brookings Institute, among others, have made findings that reflect a haemorrhaging of potential mining royalties through underreporting. However, if governance was to be improved and tax collections increased, citizens would be able to hold incumbents to account over their fiscal spend.

South Africa had to approach the IMF for a bailout after years of mismanagement and low economic growth. Due to the country’s robust democratic culture, there was fierce debate about the bailout and how it should be used.

Ultimately, the elephant in the room in Africa’s recent debt crisis is the rise of China. Between 2000 and 2017, China extended loans totalling $125-billion to sub-Saharan African countries. Angola is the leading receiver of the loans followed by Ethiopia and Kenya. Beijing debt constitutes one-third of Africa’s debt, with 70% of contracts linked to the debt going to Chinese firms. Some of the debt is guaranteed by commodities. For instance, Angola repays its debt through oil supplies.

As Zambia battles to repay its debt obligations, the continent and international community are reminded of the deep-seated structural and systemic governance challenges that continue to undermine the continent’s development. The much-touted African Continental Free Trade Area will not deliver any results if the member states fail to rein in their fiscus. China must be an honest partner on the continent instead of creating relationships that force African countries to be financially and politically indebted to its rising power at the expense of their citizens’ welfare. DM

Azwimpheleli Langalanga is a Senior Associate: International Trade and Investment Policy at Tutwa Consulting Group where he specialises in the laws and policies regulating international trade and investment, including international political economy. He holds a Master of International Law and Economics from the World Trade Institute in Bern, and a Master of Laws in Labour Studies from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.