OP-ED

Students will return on an unequal footing because of poor remote-learning access

Much has been written about how the Covid-19 lockdown and the subsequent shutdown of campuses have revolutionised tertiary education through remote learning. But given South Africa’s vast inequalities, including inequalities in access to the internet and to devices, the proverbial playing field is anything but level.

South African university and college (tertiary education) students will be welcomed back to campuses around the country as lockdown Level 1 takes effect. However, the journey to this point has been fraught with challenges and students are likely to return on an unequal footing. Institutions have shown varying degrees of capability to roll out remote learning, necessitating an extension of the academic year; the National Student Financial Aid Scheme has been under fire for failing to provide students with laptops as promised; and students have been battling with an inadequate supply of data to access online learning materials.

Nzimande: Academic year ends in February 2021 — and corruption fears delay NSFAS laptop tenders

Additionally, glaring structural inequalities shape the household environment in which students have been expected to learn new academic material online. Household access to electricity, a stable internet connection and a suitable device off which to learn can be considered three minimum resource requirements for remote learning to take place. However, we find that more than 50% of students reside in municipalities where less than 10% of households have access to all three of these resources.

Where do tertiary students reside?

On the whole, the distribution of students mirrors overall population density closely; provinces with low population density have low student numbers (Statistics South Africa). Figure 1 shows that university student origins are more concentrated than TVET student origins. For example, just over 25% of all students in the university sector come from three municipalities. For TVET students the concentration is lower; 25% of all students in the TVET sector come from six municipalities.

The City of Cape Town is the municipality most densely populated with TVET students. The second, third and fourth most populated municipalities with TVET students overlap with the top three most populated municipalities with university students, namely: Ekurhuleni, eThekwini and the City of Tshwane.

Figure 1: The distribution of university and TVET college students by municipality.

Figure 1: Source: Authors’ own calculations using data from Higher Education Management Information System [HEMIS] 2018, Technical and Vocational Education and Training Management Information System [TVETMIS] 2019. Sample: Number of students: N=1 043 646 (University); N=648 498 (TVET)

Using the 2016 South African Community Survey Data, we construct indicators for access to electricity, access to a stable internet connection and access to a device (tablet or computer) in the home. Each indicator is aggregated to the local municipality level to estimate the proportion of all households in each municipality with access to the respective resource. University and TVET college students are then mapped to these municipality-level indicators using institutional data.

The average characteristics of households in more densely populated municipalities will contribute more significantly to the aggregate indicator. Our estimates of access to remote learning resources below should be understood with these distributions in mind.

We find the majority (97.4%) of university students reside in municipalities where more than 75% of households have access to electricity, as do the majority of TVET students (96.57%). However, a “reliable” supply of electricity is in question given the intermittent load shedding periods the country has had to embrace.

In addition, internet connectivity levels are low. The majority (53.15%) of university students come from municipalities in which just 10 to 20% of households have access to the internet. On the other hand, the majority of TVET students (48.9%) reside in municipalities in which fewer than 10% of the households have access to an internet connection.

On average, just under half of university students reside in municipalities where between 30% and 47% of households (at the upper end) have access to a device (computer or tablet, which may or may not be shared). In comparison, only one-third of TVET students reside in municipalities with similar device access levels.

It should be noted, though, that our results only elicit the average characteristics of households in students’ municipalities, and not the characteristics of student households themselves. Nonetheless, they are broadly illustrative of low levels of access to the necessary – although not sufficient – remote learning “resources” in municipalities in which students reside.

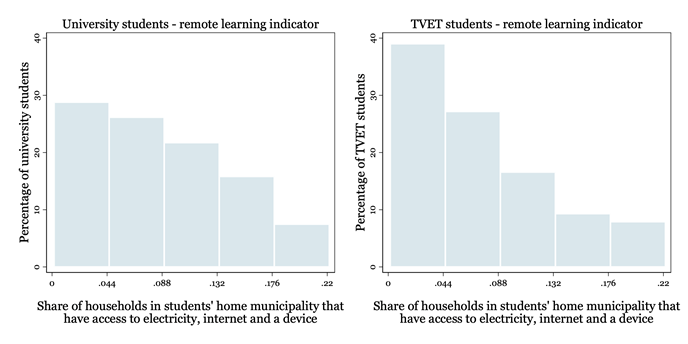

We additionally construct a single indicator which measures if a household has access to all three of these resources, and aggregate it to the municipality level (Figure 2). We estimate that more than 50% of both university and TVET students reside in municipalities where fewer than 10% of households have access to all three resources – 39% of TVET students come from municipalities where fewer than 4.4% of households have access, compared to 29% of university students. This means a higher proportion of TVET students compared to university students are clustered at the lower end of the distribution, once again foregrounding the relative disadvantage of TVET students regarding ability to learn remotely.

Figure 2: Percentage of students by share of households in their home municipality with access to electricity, internet and a computer or laptop in their home (access to all remote learning resources)

Source: Authors’ own calculations using data from Community Survey 2016 (StatsSA), HEMIS 2018, TVETMIS 2019. Community survey data are weighted using household-level post-stratification weights. Sample: N=1 043 646 (University); N=648 498 (TVET)

Remote learning without adequate resources

Given these findings, the impact of protracted online learning is unlikely to have been negligible, and students who are not yet able to return to campuses will likely face continued constraints to their learning. Therefore, lack of access to remote learning resources is likely to have disadvantaged, and continue to disadvantage, students during this time. Although on-campus living presents a way – albeit imperfect – of equalising access to resources for students from various backgrounds, this setback is unfortunately unlikely to be remedied solely by students returning to campus.

The poor at universities left behind in lockdown, says student union

While solutions to remedy the situation have been implemented to varying degrees across the sector, these have been implemented in an uncoordinated manner, and students have remained underserved. It seems, additionally, that judging solely on the average municipality-level characteristics of students’ homes, TVET students have fared worse than university students. However, we acknowledge that varying degrees of institutional advantage exist across the university (and TVET college) sector too. DM

This work is funded by the Spencer Foundation. It is an introductory analysis to a larger project within the Siyaphambili research group investigating the effects of the Covid-19 health crisis on inequalities in the South African tertiary education sector.

Emma Whitelaw is a doctoral student in Economics at the University of Cape Town. She is a graduate associate at the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU) for the Siyaphambili Post-School Research group, where her research focuses on post-school education and training. She receives funding from the National Research Foundation.

Samantha Culligan is a masters student in Economics at the University of Cape Town. She is a research assistant at SALDRU for the Siyaphambili Post-School Research group, where her research focuses on post-school education and training. She receives funding from the National Research Foundation.

Nicola Branson is a Senior Research Officer in SALDRU in the School of Economics at the University of Cape Town. She heads the Siyaphambili Post-School Research group, where her research focuses on inequalities in access to post-school education and subsequent transitions into the labour market.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider