Monster, Unmasked

Mary Trump’s dissection of her Uncle Donald: Painful, Surgical, Revealing

Mary Trump’s engrossing description of her uncle in her new book, ‘Too Much and Never Enough’, dives deep into family history and explores the making of a monster – a man who just happens to be the American president.

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” — Leo Tolstoy, the opening words of his novel, Anna Karenina.

Over the past weary months of the Covid-19-enforced lockdown, this author suffered from a curious inability to sit still long enough to concentrate on a weighty, serious book. Then, suddenly, in the past several weeks, I was seized with the need to begin an ambitious reading programme of novels — perhaps driven by the realisation — or the fear — that the current Covid-19 lockdown might never really go away and we might be forced to live out our lives vicariously, through computer and video screens.

As a result, modern classics like Junichiro Tanizaki’s The Makioka Sisters, Karl Maria Remarque’s The Way Home and Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny all passed through my hands over the past couple of weeks to savour yet again. In addition, inevitably, I’ve had to read exposes of the incumbent American president such as John Bolton’s The Room Where It Happened and Mary Trump’s Too Much and Never Enough, along with the usual, unending flood of contemporary political analysis about South Africa, America, and global issues.

Tanizaki’s massive novel described an old Japanese merchant family now uneasily poised between the old ways and the modern world, just as World War II was about to erupt. Remarque’s book, a sequel to his All Quiet on theWestern Front, detailed the struggles of comrades from the battle lines of Germany’s defeated army as they coped with their new, straitened circumstances. And Wouk’s book imagined a mutiny on board an American destroyer escort on station in the Pacific in the midst of World War II, as a new captain, a man so war-weary, he is on the verge of a nervous breakdown, is confronted by his officers and removed from his position. (Watch Captain Queeg’s testimony at the resulting court martial here from the film of the novel and play.)

For each of these sagas, a key element has been the psychological state of the protagonists as they have wrestled with the rapidly changing circumstances in a world where hallowed verities were suddenly making less and less sense than ever before.

Naturally, our reading programme also led me to two new volumes about Donald Trump and the Trump presidency.

We recently reviewed John Bolton’s memoir of his White House year-and-a-half in which Bolton had declared the president was simply unfit for duty by virtue of both temperament and ability. Bolton’s book has become just one more in a growing stack of books — some directly about the president and his ways and wiles, while others more subtly about the nature of leadership, but coming from now-former aides and officials in the Trump administration and a few close, but outside observers. There is now even a journalist’s biography of First Lady Melania Trump and her own rise to prominence as she comes to grips with her new-found status.

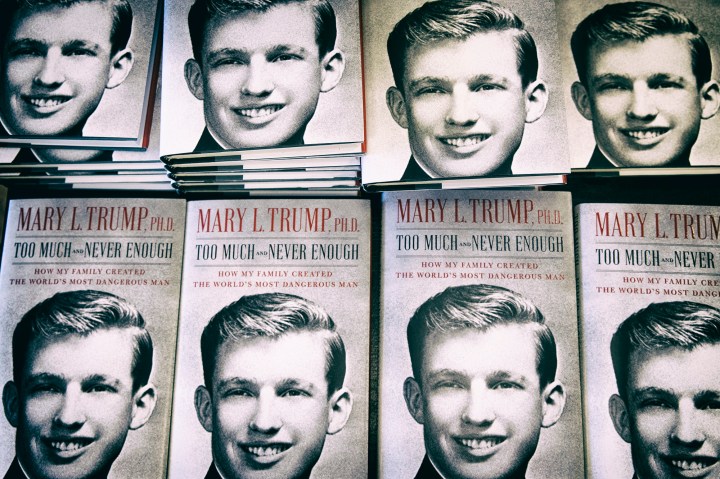

Most recently, now unshackled after an unsuccessful court challenge on the part of the president to block its availability to readers, comes Mary Trump’s contribution. It is the rather slender but explosive volume, Too Much and Never Enough. The author seems ideally positioned to offer unique insights about the mind and manners of Donald Trump for two reasons. First of all, she is a niece of the president as the daughter of his late older brother. At the same time, she is also a trained clinical psychologist. And she can write. Well.

Mary Trump unwraps the development of Donald Trump back to the formative influences on him from the impact of the future president’s father, Fred Trump, as well as Donald Trump’s participation in the deeply destructive relationship between the two boys and between the father, and his first-born son, Freddy, presumptive heir to the family business.

For decades, the Trump family had achieved growing material wealth, based on the elder Trump’s ability to manage construction projects, to keep costs down, and crucially, to manipulate political influence to secure government loan guarantees to construct solidly built, but unprepossessing apartment blocks in New York City throughout the city’s outer boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn (i.e. not Manhattan), to meet pent-up demand for new housing from the city’s working and middle-class families.

For Trump senior, dominating family values were drawn from the lessons of Reverend Norman Vincent Peale, a popular 1950s preacher and advocate of his church (a kind of precursor of the so-called “money churches” so familiar to South Africans now) — and the author of The Power of Positive Thinking. Boiled down to its basics, Peale’s guidance was: Optimism begets success; success is measured in tangible, monetary terms; and monetary success begets yet further optimism and thus becomes a tangible manifestation of God’s love. A positive feedback loop that practically justifies sharp business practices.

The Trump family — under the leadership of Fred Sr — took this injunction to heart, but there were two added dimensions in that family. The first was that women — adults or children — really didn’t matter much in the broader scheme of things; and the second was that it was impossible to gain any warmth, security and love, absent success, as Fred Sr defined it. As Freddy, the son, was pulled away from the family business and into what he had hoped would be a career flying commercially, his father gave him little encouragement.

Soon enough, Fred Sr had completely transferred his emotional support instead to his second son, Donald, the new heir-presumptive, whom Fred Sr judged had the requisite brashness needed to move the Trump business empire into bigger things, conquering Manhattan, the pinnacle of business and worldly success, and then elsewhere, such as the casino ventures in Atlantic City, an hour’s trip from greater New York City. (Fred Sr was not a true fan of the casinos, but he was there to offer financial backing when it became apparent the casino business was not a total licence to print money after all.)

From Mary Trump’s unrelenting memoir, we learn that Trumpian materialism and success are really the only things that bind this family together. No one ever seems to speak of ideas, hopes, dreams, aspirations, or ideals (except Freddy’s abortive effort to escape the vice by becoming an airline pilot). Save for Rev Peale’s best-seller, this family is not moved by books, plays, sports, music, museums, or art. There are no great causes to celebrate or support. There are no boards of charities or philanthropies to join and organisations to nurture. There is just money and the making of it through business smarts, guile, political connections and borderline illegal behaviour.

In the way Mary Trump describes the construction of Donald Trump, the result of all this grooming by his father has created within the son are both his by now well-known narcissistic personality disorder and a borderline sociopathic personality. (Asked in a television interview the other day, if, based on her clinical knowledge of him, Donald Trump should even be president, her answer was an emphatic judgment that he must resign for the good of the nation.)

Mary Trump makes it clear her uncle has worked hard to convince the world — and probably himself — that his successes are entirely of his own making, despite the now well-known facts that Fred Sr had shovelled major amounts of money to underwrite Donald Trump’s riskier ventures into gambling casinos in Atlantic City as they failed one after another. As she writes: “Donald today is much as he was at three years old: incapable of learning, or evolving, unable to regulate his emotions, moderate his responses, or take in and synthesize information.

“Donald’s need for affirmation is so great that he doesn’t seem to notice that the largest group of his supporters are people he wouldn’t condescend to be seen with outside of a rally. His deep-seated insecurities have created in him a black hole of need that constantly requires the light of compliments that disappears as soon as he’s soaked it in. Nothing is ever enough. This is far beyond garden-variety narcissism.

“Donald is not simply weak, his ego is a fragile thing that must be bolstered every moment because he knows deep down that he is nothing of what he claims to be. He knows he has never been loved. So he must draw in if he can by getting you to assent to even the most seemingly insignificant thing: ‘Isn’t this plane great?’ ‘Yes, Donald, this plane is great.’ It would be rude to begrudge him that small concession. Then he makes his vulnerabilities and insecurities your responsibility: you must assuage them, you must take care of him. Failing to do so leaves a vacuum that is unbearable for him to withstand for long.”

That is definitively not the kind of personality one wants controlling a nation’s nuclear launch codes and the most powerful military on the planet. But unfortunately, whether he likes it or not, he is now at the centre of what should be efforts to deal with the fate of the nation in coping with a massive pandemic, a seismic, deep economic disruption as a result of the disease, and widespread racial and social turmoil, all at the same time.

But Mary Trump goes still further. She writes of her uncle and the most powerful man in the country: “From his childhood in the House to his early forays into the New York real estate world and high society until today, Donald’s aberrant behavior has been consistently normalised by others. When he hit the New York real estate scene, he was touted as a brash, self-made dealmaker. ‘Brash’ was applied to him as a compliment (used to imply self-assertiveness more than rudeness or arrogance), and he was neither self-made nor a good dealmaker. But that was how it started — with his misuse of language and the media’s failure to ask pointed questions.

“His real skills (self-aggrandizement, lying, and sleight of hand) were interpreted as strengths unique to his brand of success. By perpetuating his version of the story he wanted told about his wealth and his subsequent ‘successes’, our family and then many others started the process of normalising Donald.”

By now, of course, some of the more tawdry details of those financial manipulations have become better known, thanks to the diligent work of reporters from The Washington Post and The New York Times, among other spaces. But at the time of the first election, this was not so well known by most people, even otherwise careful analysts.

Drawing on her psychological training, Mary Trump has delved into considerable depth over the Trump family’s inner dynamics, and it is only here where her narrative sometimes falters when the text begins to resemble more the doctor’s notes in a psychiatric patient’s medical file than the vivid, and entirely gripping tale of family intrigue, betrayals, and trials she tells in the rest of her book.

In fact, that storyline nearly takes on an operatic quality with tragedies and bodies scattered about on stage. And it is here, too, where Tolstoy’s judgment about the nature of unhappy families matters, since the Trump extended family was a decidedly ruthless, unhappy, even toxic environment in which to grow up in, according to Mary Trump’s telling of it.

When Freddy’s life shrivels due to alcoholism and divorce, he is eventually taken back into the family home for his last months, but was in such a mean-spirited way that it only seems to have made his circumstances even worse, until he finally passes away, barely mourned or remembered.

Over time, Freddy’s two children (Mary and Fritz) are progressively driven beyond the family’s inner circle that now revolves around Donald, as Fred Sr begins his descent into Alzheimers. This includes the legal legerdemain that deprives Freddy’s two children (and thus Mary’s brother’s son as well) of anything close to their fair share of the family fortune, and even access to trust funds established decades earlier for them — even to the point of cutting them off from the group medical plan that covers the entire extended family.

These emotional and financial wounds clearly have hurt Mary Trump deeply, giving the saga a contemporary version of the Cinderella tale as its structure. In response to all the pain and anguish, however, not only has she not forgotten the large and small wounds, but she has used this volume to set it all down for everyone to read and share — and to be deeply embarrassed by the man Donald Trump became.

But she also broadens her reach in her judgments about her uncle by applying this clinical evaluation of her uncle to encompass his dealing with national and international affairs.

She explains: “After the election, Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-un, and Mitch McConnell, all of whom bear more than a passing psychological resemblance to Fred [Sr], recognised in a way others should have but did not that Donald’s checked personal history and his unique personality flaws make him extremely vulnerable to manipulation by smarter, more powerful men.

“His pathologies have rendered him so simple-minded that it takes nothing more than repeating to him the things he says to and about himself dozens of times a day — he’s the smartest, the greatest, the best — to get him to do whatever they want, whether it’s imprisoning children in concentration camps, betraying allies, implementing economy crushing tax cuts, or degrading every institution that’s contributed to the United States’ rise and the flourishing of liberal democracy.”

All of this raises one worrisome question, of course. Where was Mary Trump four years ago that she couldn’t sound the tocsin for voters, going on every news channel and social media outlet in the land to warn of the coming apocalypse?

Still, better late than never that she has raised the alarm now. The population of the US does have a second bite at this particular apple in just a few more months. And they can make such a choice, if they will but heed a woman scarred by an entire life’s exposure to a man she has now laboured hard to unmask for the monster he truly is. DM