MERE IMMORTALS

Eugene Marais: Worker in a science yet unborn

Nearly 100 years ago, in a country far from the universities of Europe and America, in an internationally peripheral language and in non-serious, unscientific publications, Eugene Marais came to conclusions about life on Earth which were among the most profound scientific discoveries of the 20th century.

Many considered him to be mad, and there were times when he would have agreed with them. There were other descriptions: muckraking journalist, hypnotist, drug addict, lawyer, surgeon-general, genius, a founding father of Afrikaans literature and one of the finest naturalists South Africa has ever produced.

But for Edna Cross, a 10-year-old who shared a house with him in Pretoria, Eugene Nielen Marais was simply uncle Eugene – the most magical adult she ever knew.

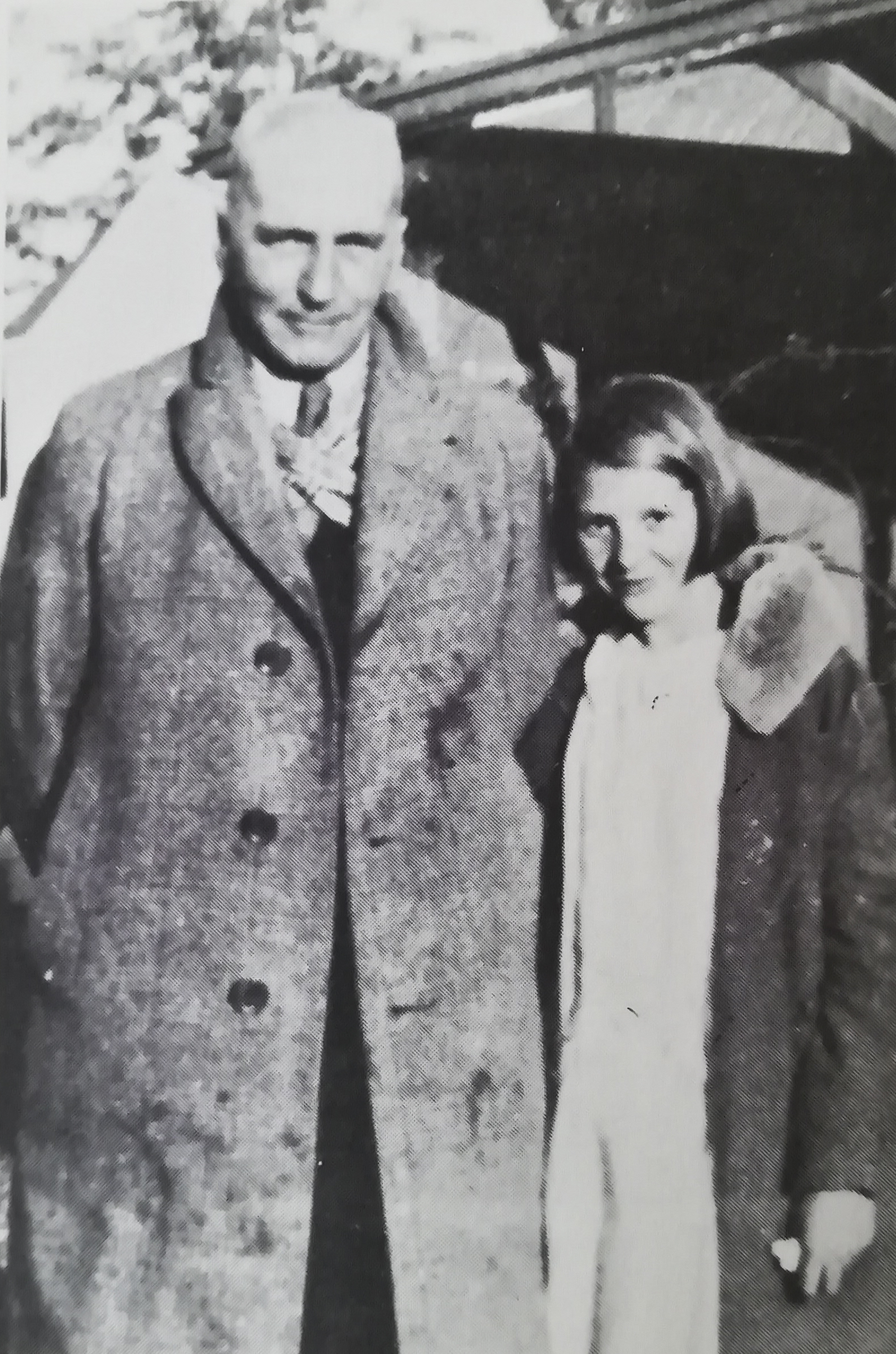

Eugene Marais with Edna Cross in 1935 (picture from the book Dark Stream by Leon Rousseau)

“There is nobody like him today and there will never be anyone like him again,” she was to say 30 years after his untimely death. “His room was a wonderland. I remember the numerous books and the skulls on top of the wardrobe – a human skull and an ape skull – and the collection of knives. His stories absolutely enthralled us. A single story could last for weeks…”

In the summer of 1936, Marais put the barrels of a 12-bore shotgun in his mouth and pulled the trigger. More than six decades later, his stories still enthrall us and challenge science – he was that far ahead of his time.

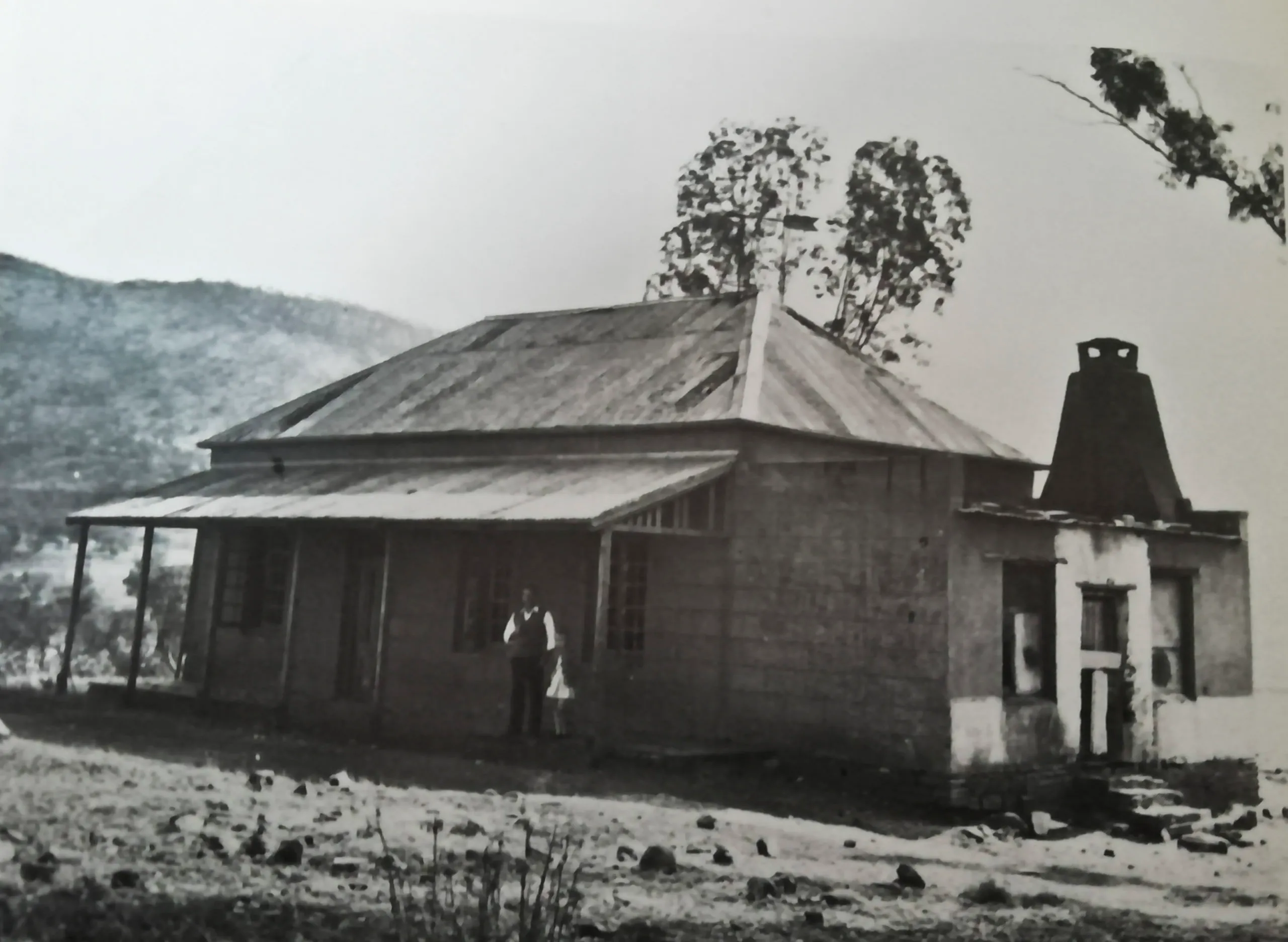

The rondawel where Marais spent his last days (picture from the book Dark Stream by Leon Rousseau)

The house where Marais borrowed a shotgun and killed himself (picture from the book Dark Stream by Leon Rousseau)

We will never know whether his addiction to morphine enhanced his scientific insights or blocked even greater achievements. The drug was possibly a mistake: When Marais was a baby, no well-equipped household medicine cabinet was without an opium-based anodyne for pain, nervous attacks or hysteria. Babies were lulled with concoctions such as Dalby’s Carminative, McMunn’s Elixir, Mother Bailey’s Quieting Syrup, leaving countless youngsters calm, but addicted. When, as a young journalist, Marais hit stressful times, it was to morphine that he turned. When his young and beautiful wife, Aletta, died in childbirth, it became his companion.

By the age of 12, he was a published poet and was reading Shelley, Byron, Coleridge, Keats and other 19th century poets. He kept a live python and stored his pens in a human skull on his desk.

Periods of heavy addiction and other times of withdrawal were to turn him increasingly into a recluse – seeking out the healing power of South Africa’s wildest places, far from humans who would pass judgement on his deplorable condition. Disillusionment with the outcome of the Anglo Boer War simply speeded his trajectory. Oddly, science was to gain from this.

Marais was born in 1871 in Pretoria, then still a frontier town. Lions roamed where the Union Buildings now stand. The area around his home teemed with mambas and puffadders. As a youngster, he kept scorpions – much to the alarm of his six prudish older sisters.

In his excellent biography, Dark Stream, Leon Rousseau described Marais as growing up “with the acute consciousness of sin and evil which typified his era, his church, his nation and his family, elements which can hurl a man from side to side like dice in a glass.”

By the age of 12, he was a published poet and was reading Shelley, Byron, Coleridge, Keats and other 19th century poets. He kept a live python and stored his pens in a human skull on his desk. By 16, he had matriculated and by 19, he was the editor of a cheeky Dutch-Afrikaans newspaper named Land en Volk.

Marais as a young journalist

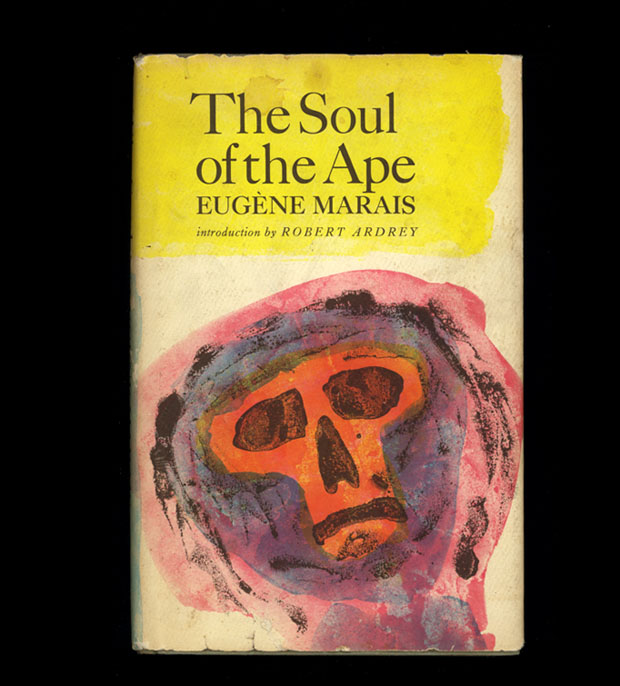

In 1896, Marais sailed for London to study law, but seemed to spend more time with a young woman named Susanne and rearing a baby chimp in his rooms in Lewisham. The former was to break his heart, the latter led to his first steps on a path which was to end – in the declining years of his life – with the ground-breaking study entitled The Soul of the Ape.

He was among a class of intelligent and articulate Afrikaners of the time who, according to the prominent poet and critic NP van Wyk Louw, had “started dreaming in a different key”.

Dark Stream makes gripping reading, dealing as it does with the involvement of this enigmatic man with the Jameson Raid, the Anglo Boer War, his journalism, his hypnotic effect over women, horses and chickens, his warmth towards children, his work with termites, baboons and evolution, and his struggle with morphine. But to appreciate Marais the scientist, we need a different point of entry.

What was it, he puzzled, that makes termites different from baboons? And in what ways were they similar? His conclusion to both questions, as he sat in a hut amid primates and wild mountains, went beyond even Freud: the answer was memory.

In his extraordinary book The Life of the Cosmos, American physicist Lee Smolin has an intriguing chapter entitled simply “What is Life?” (if you need to know the answer, read the book). In it, he makes a broad, but well-supported statement: “The understanding that life on this planet as an interconnected system must be considered one of the great discoveries of science, perhaps as profound as the discovery of natural selection.”

Keep that in mind, but now let’s return to Marais. In an attempt, possibly, to decrease his dependence on morphine, Marais hitched a ride on a horse cart heading for the Waterberg, northwest of Pretoria, little realising its wilderness would hold him there for a number of years. It was a place, he was to write, which he’d always associated with the wonders of unpeopled veld, “uninhabited by white men – and the wild animals were still there”.

On a farm deep in the berge (mountains), far from the scientific storm raised by Darwin’s conclusions on the origin of species or Freud’s work on the psyche, he would study two creatures which, on the face of it, had absolutely nothing in common: termites and baboons. Both fascinated him – as did all wild things.

But, insulated from the storm, Marais took a leap beyond Darwin. What was it, he puzzled, that makes termites different from baboons? And in what ways were they similar? His conclusion to both questions, as he sat in a hut amid primates and wild mountains, went beyond even Freud: the answer was memory.

Marais began studying termites on a Rietfontein farm. On the first page of The Soul of the White Ant, he describes this study, rather tellingly, as “an investigation into animal psychology”.

He watched them flying from termitaria in their thousands after rain, the female flicking off her wings as she landed: “quicker than a woman who discards her evening gown.” Then she’d raise her hindquarters and signal for a male. Having lured one, he discovered, the pair would rush round searching for a place to begin digging the first shaft of a new termitarium. The queen would grow immense, spawn hundreds of thousands of workers and soldiers, and control the hive for many years.

What Marais noticed, more importantly, was that if the pair was somehow prevented from flying, their future would end there and then. A few flaps and they could breed. Ground them, he found, and the chain of their life would be broken. They had to pass through every stage or they were doomed.

His extensive study was to have two important conclusions, both pioneering, but virtually unnoticed by the wider scientific community of the time.

Firstly, the whole termitarium needed to be considered as a single organism whose organs had not been fused together as in a human being. The queen was the brain and womb, the workers were the mouthparts and tissue builders, the soldiers acted as white blood corpuscles and the humus gardens were the stomach. And secondly, the actions within the termitarium – and by extension, the “hive mind” – were completely instinctive. Any variation would endanger the creature’s particular, hard-won ecological niche.

Marais began writing Soul of the Ape in 1916, but never finished it. It was pieced together years later and published posthumously. His studies, however, began years earlier in a Waterberg devoid of guns, which had been confiscated from farmers after the Anglo Boer War. Conditions for getting close to a troop of wild chacma baboons – which had never heard a shot fired – were ideal.

Baboon (Photograph: Don Pinnock)

“We approached this investigation without any preconceived ideas,” he was to write. “Although at the beginning inexperience may have left much to be desired in our methods, we had at least no theories to verify.”

But science requires theories and Marais devised a few of his own. Unlike termites, he suggested, chacmas – and by extension all primates – had the ability to memorise the relationship between cause and effect. They could accumulate personal memories and, importantly, could therefore vary their behaviour voluntarily.

This was not an evolutionary refinement of instinct, but another type of mind altogether, which Marais named “causal memory”. While the hive mind of termites was all instinct, the causal memory of the chacmas operated quite differently, virtually submerging the instinctive mind. But why? Here comes the good bit…

Natural selection, he said, was not so much the survival of the fittest as Darwin had insisted, but the line of least resistance. Those species best able to adapt to their specific environment survived more surely than those that didn’t. Natural selection, therefore, had a tendency to localise, as well as specialise, species.

Perhaps even more importantly, Marais’s ideas were grounded in his intuition that life on this planet is an interconnected system.

The downside, of course, was that sudden environmental change meant the destruction of specialists because instinctive memories only adapt over eons of time. The solution? Listen to Marais at his lyrical and scientific best:

“If we picture the great continent of Africa with its extreme diversity of natural conditions – its high, cold, treeless plateaus; its impenetrable tropical forests; its great river systems; its inland seas; its deserts; its rains and droughts; its sudden climatic change capable of altering the natural aspects of great tracts of country in a few years – all forming an apparently systemless chaos, and then picture its teeming masses of competing organic life, comprising more species, more numbers and of greater size than can be found on any other continent on Earth, is it not at once evident how great would be the advantage if a species could be liberated from the limiting force of hereditary memories?

“Would it not be conducive to preservation if, under such circumstances, a species could either suddenly change its habitat or meet any new natural conditions thrust upon it by means of immediate adaptation?”

What then would be the nature of the change necessary to bring this about?

“No generalising perfection of hand or foot, nor the attainment of the upright position, nor the transformation of any function in any single organ could render a species immune from the danger inherent in suddenly changing conditions.

“It is not conceivable that it could have been attained in any other way than through a modification of the brain and its functions. In other words, the attributes selected had necessarily to be psychic.”

These adaptations had allowed primates – particularly humans – to penetrate the most varied of natural environments. We became, in the words of Marais, “citizens of a larger world.” In essence, pan-niche apes.

It is hard to believe that Marais was formulating these ideas over 100 years ago. They raise important questions for psychology and the notion of the unconscious mind and they anticipate the discoveries by Raymond Dart, Louis Leakey and others which support the thesis that the human adventure began in Africa. They also demonstrate the wisdom – later followed by work on primates by researchers such as Jane Goodall and Dianne Fossey – that the only sensible way to study wild creatures is in the wilds.

But, perhaps even more importantly, Marais’s ideas were grounded in his intuition that life on this planet is an interconnected system. By the end of the 20th century, this would become a basic natural science principle – ecology.

Marais wrote the Soul of the White Ant in Afrikaans in newspaper instalments and it was only brought to wider attention by being seemingly plagiarised by a Belgian Nobel prize winner named Maurice Maeterlinck. The Soul of the Ape was incomplete and originally published only in South Africa. Marais is remembered more for his contribution to Afrikaans literature than to science.

When social anthropologist Robert Ardery dedicated his path-breaking book, African Genesis, to Eugene Marais, the reaction from the world’s scientific community was: “Eugene who?”

Ardrey’s reply came in an introduction to a Penguin edition of Marais’ work on ants and baboons published in 1973: “As a scientist he was unique, supreme in his time, yet a worker in a science then unborn. He was a freak, spawned by the exuberance of mankind, an immortal who speaks from his grave: beware, and do likewise. That he died by his own hand may seem as an afterthought.”

But Marais left us with a warning. Natural selection requires both a challenge and a response. To the extent that modern societies conquer the challenge, he wrote, they dilute their ability to respond.

We are no longer merely altering our particular habitat, we’re altering our entire environment as well. This can bring about great changes – and dangers. Will we be able to respond as an entire species? Was it morphine or prescience that made Marais think it unlikely? DM/ML

The Dark Stream by Leon Rousseau is published in English by Jonathan Ball (Johannesburg). Books by Marais may be harder to track down. They include The Soul of the Ape, The Soul of the White Ant (Penguin, London); The Road to Waterberg (Human and Rousseau, Cape Town) and My Friends the Baboons (Methuen, London). See also Meesterverhale van Eugene Marais by Merwe Scholtz (Human and Rousseau, Cape Town). A brilliant film, Die Wonderwerker, of Marais’ life was made by Katinka Heynes and is available on Showmax.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider