THE IMAGINARIUM

Owanto: An artist who asks you to look and reflect

‘This is not a time to be afraid, it is not a time to let our guard down. Women and girls need our support’, says Gabonese-French artist Owanto. In this series, we talk to artists, creatives, designers and musicians about their work, their inspiration and the challenges they face in today’s different reality.

“My name is Owanto, daughter of a Gabonese mother and French father. I was born in Paris and raised in Libreville, Gabon. I moved to Europe to study Philosophy, Literature and Languages at the Institut Catholic de Paris in Madrid, Spain,” says the 67-year old multidisciplinary artist, whose work – photography, videos, performances – focuses on the female condition, emancipation and the breaking of silence.

Feeding my Ancestor – Tobacco, 2018, Photography & embroidery on canvas 96 x 131 cm

“The feminine as creative energy is a constant in my narrative and is intimately linked to my childhood in Gabon where women represent the pillars of the family.” Indeed, women prevail throughout the artist’s work, from Gabonese Ladies, a video projection featuring “elderly ladies, acquaintances from my past” filmed paging through photographic memories, to Feeding my Ancestor where the artist used textiles and embroideries to create an ode to her grandmother Flavienne Agnorogoule, who passed away having not enough food to eat; or Flowers, a series of images that call attention to the complex and controversial subject of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) intertwined with the colonial gaze. The latter was presented at the opening exhibition of the Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, back in September 2017.

The flowers seem to both protect the women from the voyeur gaze of the witness – The ethnologue? The colonialist? The intruder? The audience? – as well as restore what has been removed, symbolically and physically.

The Flowers series, black and white photographs of women recorded during or after initiation ceremonies, “an age-old ritual that has been used to signify the important transition from childhood to womanhood by curbing sexual desire” says the artist, are transformed with appliqués of bright and bold flowers, some almost fluorescents, a stark contrast to the original image; here, they are applied where the genitals would have been cut and left exposed to the viewer’s eyes; there, placed in corollas around the faces. The flowers seem to both protect the women from the voyeur gaze of the witness – The ethnologue? The colonialist? The intruder? The audience? – as well as restore what has been removed, symbolically and physically.

Flowers VII (Ladybird), 2020, Photograph UV print on aluminium with cold porcelain ower 182 x 129 cm (Recently exhibited at Sakhile&Me (Frankfurt))

Flowers VII (Ladybird) – detail

Flowers V, 2015, Photograph UV print on aluminium with cold porcelain ower 125 x 91 cm (Recently exhibited at Sakhile&Me (Frankfurt))

“Fighting violence against women has become my commitment to the art field in the last years. This connection to the cause has its roots in my youth, when I discovered a series of small photographs of a female circumcision ceremony among my father’s belongings.

“These images from the colonialist days were taken as ethnological documentation and sold as postcards. I remember vividly that when I saw them for the first time, I didn’t understand what I was looking at. My reaction was to stop looking and hide them from my sight, but the images stayed with me, as a graphic representation of violence in the bodies of women and girls,” she explains.

Owanto adds that “although the black and white of these photographs is an effective first filter for trauma (since hiding the colour of blood distracts us from the photographed reality), there is no complete filter that can avoid our feelings of horror in empathising with the physical and emotional pain of these girls.”

The artist found the old pictures in her father’s drawer and although she says she couldn’t understand them at the time, she couldn’t forget them either.

“After years of living with these images in my memory I found them again and I was able to look at them carefully. I was able to see them as a document of total actuality, with different protagonists, different scenarios, different reasons, but with the same misogynist violent actions. Once I really understood what they meant, I decided to enlarge them, to match the size of the shock I felt as a young woman, and suppress the black and white effect by planting in their physical and emotional wounds beautiful and sensual flower sculptures,” she says.

The beauty of the Flowers series is challenging. Yes, now they conquered your senses with their colourful and exuberant flowers, but just to make you realise the horror it is signalling a strategy allows me as an artist to contribute to the cause confronting the spectator to this issue as I was once confronted.

“For me, the action of ‘removing’ the face and intimate parts of the women in the images materially represents the effect of the mutilation on their identity. In this project, I have been aware of the risk of speaking on behalf of others, since in my previous works I have tended to deal with personal biographical issues or universal subjects. To feel that my work was an artistic contribution to the experience of other women, the project One Thousand Voices has been essential. In this project, produced in collaboration with Katya Berger (her daughter), we collect audio testimonies from Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting survivors from all over the world. These voices are the ones who speak of the loss that I represent with that ‘void’; it is their energy that inspires the blooming flowers. I am very pleased that this project has found its space in the intersection between artistic practice and activism. I am conscious of the power of Flowers’ artworks as a shared ground from which to facilitate debate, to spark it.”

One Thousand Voices project

One Thousand Voices project (Image by Wianelle Briers, Zeitz MOCAA)

One Thousand Voices project (Image by Wianelle Briers, Zeitz MOCAA)

Owanto feels that the pandemic has revealed, even more intensely, the never-ending cycle of violence against women, its threatening presence hovering like a Damocles sword, “the danger of having to be at home with their aggressors”.

Just in South Africa, 21 women and children were murdered in the last few weeks, a number President Cyril Ramaphosa mentioned in his address to the nation on 17 June 2020. He equated the recent spike in femicides to “another pandemic that is raging in our country”. At the end of March 2020, The Guardian reported that “lockdowns around the world bring rise in domestic violence”, with officials being quoted as saying violence against women possibly tripled in China, and rose “40 to 50%” in Brazil, according to a judge specialising in domestic violence.

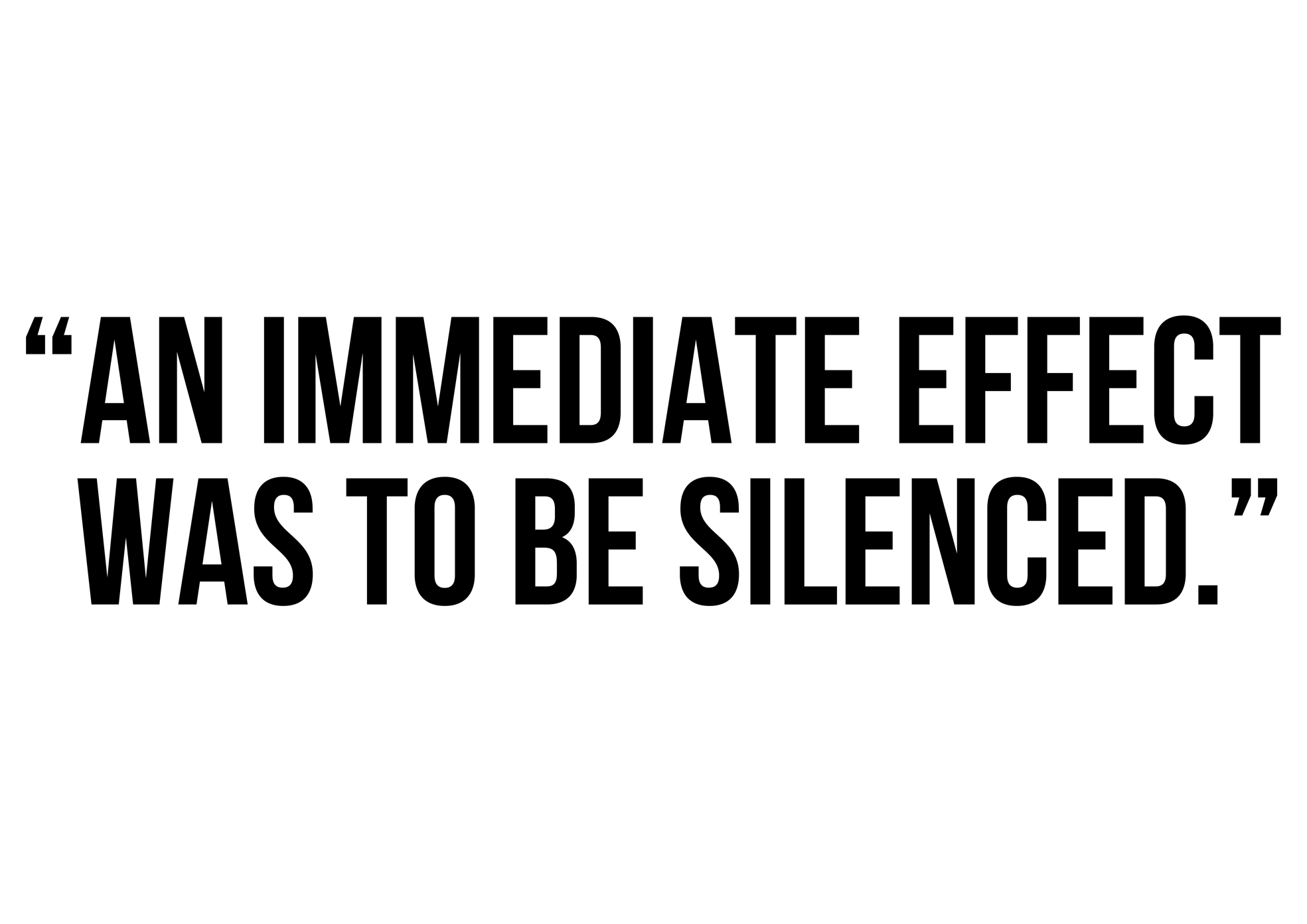

Transcription of a testimony collected by the project One Thousand Voices – Extract

Through both Flowers and One Thousand Voices, Owanto hopes to effect change: “The beauty of the Flowers series is challenging. Yes, now they conquered your senses with their colourful and exuberant flowers, but just to make you realise the horror it is signalling a strategy allows me as an artist to contribute to the cause confronting the spectator to this issue as I was once confronted,” she says.

Yet, the last few months, especially while in lockdown and now, as the pandemic transforms the way we gather and consume arts, she feels that “virtuality alone does not provide a complete aesthetic experience for all types of artwork”. It also brought fear and confusion. Still, Owanto says we cannot be afraid.

“This is not a time to be afraid, it is not a time to let our guard down. Women and girls need our support. The fight to defend survivors breaking their silence, women and girls who claim their rights to have a say on their own body, must not stop”. DM/ML

You can experience a virtual tour of Owanto’s latest exhibition at Sakhile&Me2 and engage with the artist on Instagram and Facebook. To learn more about the artist, click here.

If you would like to share your ideas or suggestions with us, please leave a comment below or email us at [email protected] and [email protected].

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of Maverick Life delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider