MOMENTS IN TIME

The path less travelled: From Genadendal to Greyton through the mountains

It’s a two-hour walk alongside the mountain from the Moravian mission of Genadendal to Greyton. But the walk, and both villages are worth it.

“We recycle steel things. Washing-machine drums, compressors and big wheels from trucks,” he says in his perfect, heavily accented English, surrounded by pieces of scrap metal in a messy little yard. Kazik Stryczynski is the blacksmith in the Overberg village of Greyton.

Blacksmith Kazik Stryczynski (R) and his assistant Ferlin Robertson (L) (Image courtesy of Angus Begg)

Stryczynski doesn’t work in Greyton. He commutes to the historic Genadendal Moravian mission, 5km around the corner by road or a two-hour walk alongside the mountain.

“Look at this heater,” he says, an impish grin spreading as he winks at his assistant of two years, Ferlin Robertson. “It was a gas cylinder… you want to buy it?”

Stryczynski works in a yard surrounded by 100-year-old oak trees and adjacent to the oldest working mill in the country, behind the Genadendal museum.

“It’s a beautiful facility,” says Stryczynski. “It’s peaceful, and anyway, Greyton is too expensive.”

A suite of circumstances led to him taking over from the previous blacksmith.

Stryczynski represents the curious and historical link that exists between affluent, sometimes Victorian Greyton and the charming, historical and impoverished Genadendal. It was this that I had set out to explore, the physical and human connection between the two villages.

“We work with forging, ornamental bars, balustrades, specialised doors, items people need. These days everything bought in a shop breaks.”

Stryczynski’s heaters, particularly the one made from a gas cylinder, are what Constantia residents might call “stunning”. But I tell him I’m not buying. This time.

“My stuff is heavy duty, guaranteed more than five years,” he says, with a wide-eyed twinkle. Given the rough, industrial nature of his newly morphed creations, I’m not surprised.

But it’s something around 300 years older, and finer, that first caught my attention.

Genadendal’s signature Moravian church (Image courtesy of Angus Begg)

It was the picture-perfect mission church complex, the foundations of which were created by a Moravian missionary named Schmidt in 1748. That was some months before I met the Pole.

Then, I had listened to the former curator of the Genadendal Museum, local historian and lifelong resident Dr Isaac Balie, reveal the remarkable story of Genadendal. Balie told us it was “the oldest mission station in Africa”.

“This is where South Africa’s first teacher was trained,” he said, with an “I bet you didn’t know that” pride in his brown eyes. He said that Genadendal – not Cape Town or Stellenbosch – was the site of South Africa’s first teachers’ training college. You had to be able to play three instruments before you were allowed to teach music.

We entered the part of the museum complex that houses musical instruments and Balie introduced us to “the oldest working pipe organ” in South Africa. Handmade brass instruments still hang from the ceiling. The printing presses in the neighbouring room and the machine tools up the creaky, dusty stairs, speak to the remarkable culture of workmanship available at the time, a quality that in this age of mass-production, Stryczynski aside, is increasingly hard to find.

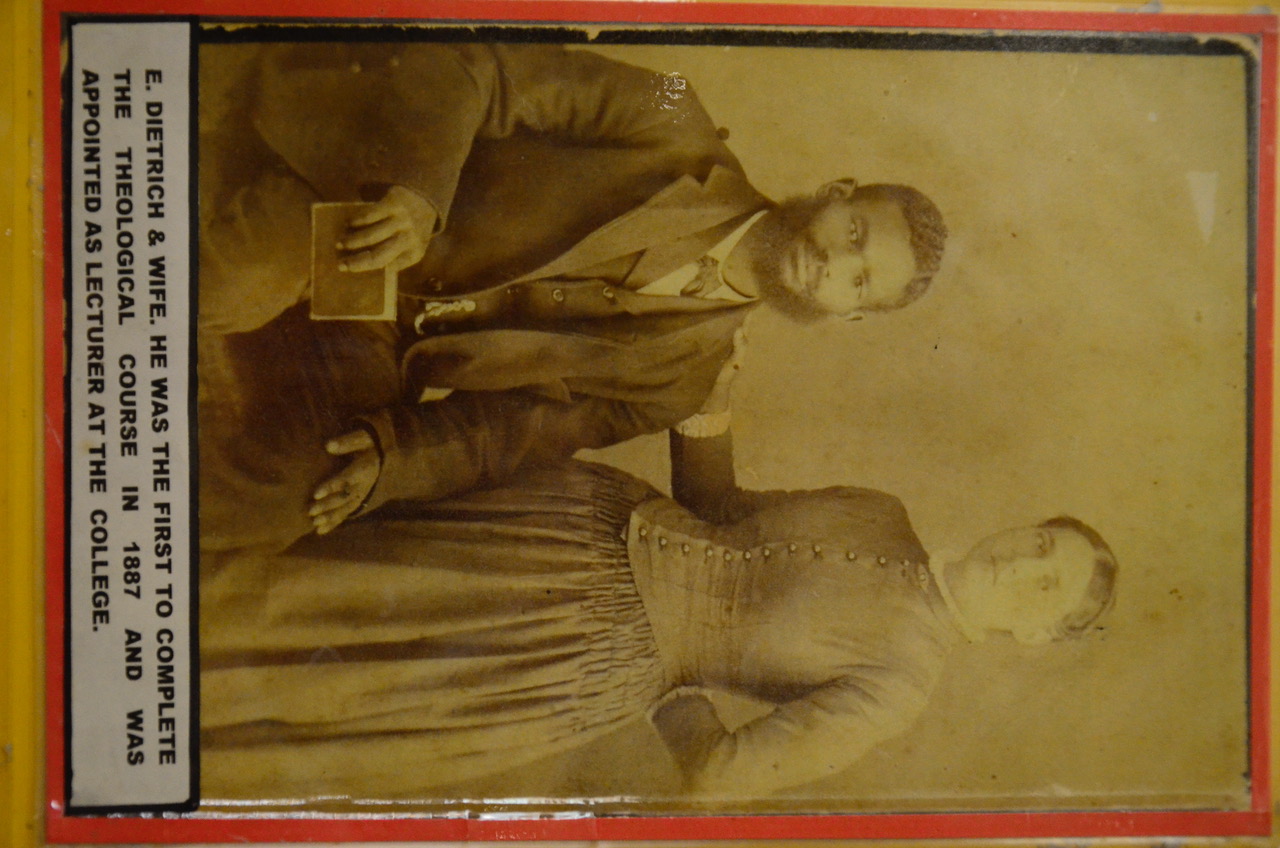

A series of photographs had caught my eye on the wall opposite a classroom of school-bunks with those ink-wells many of us used to mess around with during maths. But with no time to see it all, the pictures had to wait until this visit. I head straight back to the little classroom. In a series of poignant framed images is explained the South African reality of how we retarded ourselves as a nation, almost as we began.

There are photographs of teachers taken in the late 19th century, in poses typical of the time. A seated, bearded black man in a suit and waistcoat with what is presumed to be his Caucasian wife standing at his shoulder.

Image supplied by Angus Begg

Soon after that picture was taken, in about 1898, as the second Anglo-Boer war was about to start, the Dutch Reformed authorities in Cape Town decreed that people of colour would no longer be allowed to teach at Genadendal.

Balie tells me the tale of how the president’s Cape Town residence, Genadendal, came to be named after this village.

The fluent, self-taught German-speaker explains that after Nelson Mandela assumed office he wanted to rename the residence, from its then existing name of “Westbrooke”, which was inappropriately colonial for a newly-democratic country.

“So, Mr Mandela asked for suggestions to be sent from around the country. It so happens that he liked my suggestion. He visited us here, and I think he fell in love with it. He said he liked the meaning of Genadendal: vale of grace.”

Genadendal’s powerful history and sense of place evokes strong emotions. The warm yellow of the classic church in the village square and the imposing oaks speak of the shelter German missionaries offered the persecuted and displaced Khoi people.

The endeavour and craft in the museum and the mill, still operating, contrast with the unemployed youth sitting on the pavement outside the café as you head into the newer, residential part of the village.

It’s around the corner from the village of Greyton.

Greyton started life about 50 years after Genadendal, as a farm owned by Simon van der Stel, the first governor of the Cape, famed for his long outrides (on which he was known to acquire properties, as one did, being the boss in a new colony in an acquisitive period).

***

When wanting to get the feel of a destination, and this is a combined destination, the only way is to walk it, which gives you the opportunity to stop and smell the fynbos and photograph the sunbirds and sugarbirds feasting on protea forests. There are a few trails that allow this. The easy one is two hours.

My guide, Hilton Seekoei, whose name suggests one of his forefathers had an experience with a hippopotamus, says our trail hasn’t been used for at least a year.

Hilton Seekoei (Image courtesy of Angus Begg)

Stopping to take in the rolling mountain scenery above us to the east, north and west, the Overberg flattening out past the Sonderend River far to the south, Hilton says he has no idea about the origins of his surname. He works in the church grounds far below as a gardener and maintenance worker, but he is also a birding guide, with a Birdlife SA course as the feather in his beanie.

Seekoei points out the hill on the other side of the kloof, where bushmen paintings are found, and shows where the leopards’ likely refuge is.

“They’re seen by the camera traps, but I haven’t seen one. I’ve got a photo on my phone of a leopard killed on one of the farms. It was a big leopard.”

He tells the story of the caracal that got trapped in a bus parked in the grounds of the local school. “Sometimes caracal kill the sheep.”

Cutting our way through the dense protea forest with his machete takes a while. As the sun climbs over Grootkop peak, I try to photograph the orange-breasted sunbird. The drab female shows herself, while the gorgeous male prefers to show only glimpses.

Female southern double-collared sunbird – there is a protea forest on the hike, which attracts a host of birds (Image Angus Begg)

Looking down on Greyton, after stopping to shoot the glorious autumn colours, Seekoei offers a choice of paths down into the village. We choose Bosmanskloof, named after an early Khoi settlement in the area.

The end of the hike from Genadendal takes walkers through Bosmanskloof (Image courtesy of Angus Begg)

The first houses are framed by a quintessentially rural setting, houses on both sides of the kloof, which comprises lush common pastures for cattle and goats, and vegetable gardens. It’s a community with no barbed-wire fences around the houses.

We greet the woman smacking the mat with a brush on the verandah, and we dodge the loud, oncoming dog. Seekoei points out the houses he’s familiar with, among them his in-laws’ home, and that of Samuel, his brother-in-law, who is the educator at Genadendal.

At the end of the road, four hours after we left Genadendal, is the historic Post House.

The TV commercial famous for its tagline, “Get that man a Bells”, was shot in the cosy period-piece bar at the Post House. Inside the Post House, a man greets us with a big smile. His name is John Higginson, and with his wife, Janet Higginson, he owns the place.

John is English, and thoroughly reflective of the feel of the village I received in the neighbouring Old Potters bar and brewery the night before.

Old Potters was warmed by a fireplace. Enjoying the establishment’s dark ale, but not too much, I was introduced to some of the patrons: a TV commercials director who spends half the year on another continent, a former Joburg businessman, an author, a former London lawyer, the founder of the Greyton Classics festival and a local amateur historian.

It was very different to Genadendal. Yet, Hilton Seekoei, whose mother was a seasonal farmworker, and his father employed by the Theewaterskloof municipality, would have held his own here.

If not for his knowledge of the local nature and surroundings, then surely for his tales of catching problem snakes in the area in summer: “Ja, of course, we get puffies (puff-adders) and Cape cobras, but they usually keep to themselves,” he had said earlier in the day.

“When they don’t, I help move them.”

With a local named John (another Englishman) and his Dutch girlfriend we walked 50m down the road from Old Potters to dinner at Greyton’s new mountain-bike shop called the Hub ’n Spoke. It’s half shop, half restaurant, with ubiquitous biking paraphernalia and it’s where chef Marcel has a pasta night every Wednesday, cooking just one dish.

Home-made, thick spaghetti and a chunky, organic Napoletana sauce were on the menu that night, and we shared a long table with a Cape Town couple who spend half their time in Greyton.

The Hub’s owner, Steve, is another successful city expat. A former Cape Town businessman and biking enthusiast who used to own a designer clothing store before settling in Greyton, Steve had told me about the numerous bike trails in the area.

Back in the present, Hilton Seekoei tells me, while waiting for his lift to take him the 5km back home to Genadendal, that “for the tourist, Greyton is good, there’s lots to offer”.

One of Greyton boutique shop corners (Image courtesy of Angus Begg)

Greyton is picturesque, its setting is beautiful, and the food, drink and activity are the stuff of which good holidays are made.

I get the idea Isaac Rabie wouldn’t mind seeing a little of the same in Genadendal. And that Kazik Stryczynski, the local blacksmith, would be the first to support him. DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider