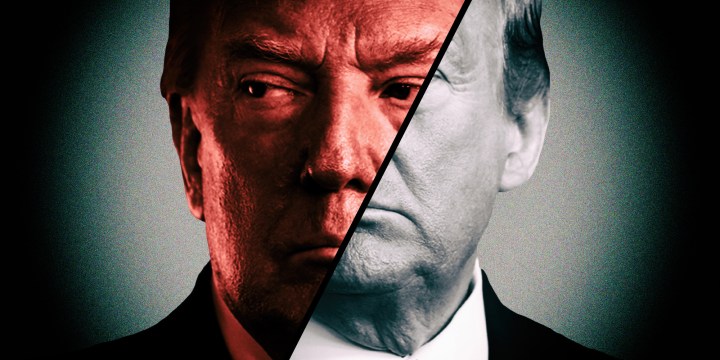

Trumpocalypse Now

Why America’s downfall matters to the world

The collapse of American leadership, so painfully achieved, will have deleterious effects on the global community. President Donald Trump’s petulant and foolish behaviour over Covid-19 has made a reversal of that downturn so much the harder.

In Ernest Hemingway’s novel, The Sun Also Rises, Mike Campbell is asked about his money troubles by his friend. The exchange between the two men goes like this: “‘How did you go bankrupt?’ Bill asked. ‘Two ways,’ Mike said. ‘Gradually and then suddenly.’ ‘What brought it on?’ ‘Friends,’ said Mike. ‘I had a lot of friends. False friends. Then I had creditors, too. Probably had more creditors than anybody in England.’”

More than 50 years ago, back when the writer was still a young idealist and hopeful for real political change in the US, back in the days of the Vietnam War, I was taking my first university-level class on international relations where I encountered concepts like “balance of power” and “realpolitik” for the first time. In this class, I was introduced to the notion that there were systems and rules through which one could understand the otherwise incomprehensible world of foreign policy. Now, okay, these rules were not quite the implacable rules of any binding international law or from a deep sense of ethics or morality, but, contrary to the writing of the 17th-century political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, the world was not always one of a war of all against all, either. There was hope.

In fact, these systems and rules had existed for millennia; far longer than any contemporary national state on the map, although they were nowhere written down, as the Code of Hammurabi or The Bible were. But, based on a close study of history, scholars and professors of this emerging discipline of international relations were trying to codify ways of thinking about inter-state relationships that, while not quite mathematical as they would be in chemistry and physics, still had predictable shapes and results.

At least in this initial course, rather limited attention was given over to the economic aspects of inter-state relations, and there was even less attention placed on the influence of individuals, the psychology of international leadership, and its effect of these on international relations. Moreover, all those “Great Men” of destiny, history, and international affairs had very little place in such theoretical constructions.

Other reading and later course work, as well as a more cautious look around the world and at history could prove otherwise. This concept of the balance of power was a useful tool for interpreting the range of international relations from the early history of China during the “Warring States” period. Similarly, it helped to understand European experience following the Thirty Years War and the “Peace of Westphalia”, and then especially in the century between Napoleon and the First World War, and in the interregnum between the two world wars.

But, it was insufficient to render a full understanding of the intense burst of European empire building after 1815 and the full onset of the industrial revolution, or even the Kissingerian policies of triangulation between the US, the USSR and China. Similarly, theory fails to provide sufficient insight into the sui generis roles and impacts of figures as varied as Genghis Khan, Sala-al-Din, Harsha, or Napoleon, or the impact of personality within the quartet of leaders – Stalin, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Hitler – in power in their respective nations throughout World War II.

And so, a broader language is necessary. This one must encompass the international relations systems approach, along with an understanding of the larger and deeper economic influences, and even the role of outsized individuals and their mindsets, in order to assess international developments. And that complex mix takes us to the question of how to evaluate the state of our current international order – and its likely future. At least now, the prognosis, as an intensive care doctor might say, is, at best, guarded.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the United States stood essentially unchallenged internationally. Unique among the combatants, its industrial base was unharmed, and given the pressures of fighting on two sides of the globe and supplying war materiel for itself and for allies around the world, the country’s industrial capabilities had actually been enhanced by the massive efforts of the war years. This included the successful development of the first atomic weapons.

By the time peace had arrived in 1945, something like half the world’s GDP was American. In the years following the war, the country simultaneously found the means to underwrite the economic recovery of Europe and to financially support a broad range of new international financial and political organs – from Nato to the World Health Organisation, even as its citizens’ material prosperity dramatically increased. While it had substantially scaled back its military, it remained an unrivalled global military power.

In domestic terms, its political, economic, financial, academic, entertainment and – increasingly – cultural achievements had come to be almost universally admired, imitated and absorbed by much of the world. (Even Ho Chi Minh’s declaration of independence from France in 1945 had drawn upon Thomas Jefferson’s words for America’s “Declaration of Independence”.) Time magazine founder/publisher Henry Luce’s boast that it was now the American Century seemed to have come true with an enormous, explosive force.

Luce had written back at the beginning of 1941 that “Throughout the 17th century and the 18th century and the 19th century, this continent teemed with manifold projects and magnificent purposes. Above them all and weaving them all together into the most exciting flag of all the world and of all history was the triumphal purpose of freedom. It is in this spirit that all of us are called, each to his own measure of capacity, and each in the widest horizon of his vision, to create the first great American Century.”

Perhaps the apotheosis of this reuse of the ideas of American “Manifest Destiny” and of the US as the “exceptional nation” came in 1969 with the simultaneous first landing by US astronauts upon the Moon’s surface, even as hundreds of thousands of US military personnel were enmeshed in a violent struggle to impose the nation’s ideals of a “Pax Americana” against Vietnamese nationalism, whose fighters were bolstered by assistance from China and the then-Soviet Union. (And, of course, all of this was taking place, just as the US civil rights revolution was sliding into a sometimes-violent urban unrest; as anti-Vietnam War sentiment and protest were rising rapidly; and as the overwhelming impact of the crossover into adulthood of the baby boom generation was affecting virtually every aspect of US life.)

But even at this seeming apogee of US power and influence, the facade was already cracking and beginning to crumble. In part this was in response to US overreach and in part due to developments in the rest of the world’s nations. Western Europe and Japan (and increasingly the four little dragons of Asia – South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore) had recovered from their respective war years and had kicked their nations into high gear economically. And also in Western Europe, the European Union was already gathering its energies and building institutions for an expansion across the continent over the next two decades to come.

While in the 1970s, China was still engulfed in the internal turmoil of the “Cultural Revolution”, a chaotic period only brought to heel by the generation of leaders that replaced Mao Zhedong and brought in a hybrid version of party political control and an increasingly free economy, the beginnings of this nation’s revival and explosive economic growth was already visible by the 1980s. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union’s disintegration along with the rest of the USSR’s empire in Eastern Europe by the last decade of the 20th century, gave rise to the overenthusiastic triumphalism of some US public intellectuals, politicians and policy aides who were asserting the end of any challenge to liberal democratic/free market ideas was nigh. Too soon, with the cheerleading, it eventually became apparent.

The lassitude of US governmental leadership has allowed the Chinese to assert a global role as providers of emergency equipment.

New technologies and ways of organising business relationships were already on the horizon, however. The internet, manufacturing automation, global supply chains, and other developments were coming along quickly. New manufacturing powerhouses were springing up across Asia, poised to take advantage of all of these innovations, even as the US’s industrial heartland was challenged to stay ahead, then stay even, then, eventually, to catch up. This challenge took place just as the shift to global supply chains became ever stronger, and automation reduced yet further the industrial employment that had been central to those traditional manufacturing areas in the US. Then the economic order was shaken right to the core with the great financial crisis of 2008-9, a failure that began within the US banking system, but whose effects soon spread globally.

By the time Barack Obama took office as president, the drain on US resources stemming from two wars in the Persian Gulf arena and in Afghanistan as well had pushed him into international policies sometimes labelled “constrainment”, as opposed to the globalism of his predecessors. It was clearly a draw-down from the overwhelming, unlimited global commitments that had evolved over several decades, and then accelerated in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Yet Obama’s approach did not represent a full-on retreat into isolationism-redux, as an echo of the years after World War I. And it also recognised the vast impact of American soft power, even if such influence didn’t easily figure into those comparative tables of missiles and tanks.

Instead, the Obama framework was meant to give the nation time to come to grips with the emerging multipolar world in which the US remained primus inter pares, yet was challenged by a newly resurgent (and increasingly revanchist) Russia under Vladimir Putin, an increasingly integrated Europe, a China now transforming into an economic behemoth as well as a growing military power, along with countries like India and Iran who were running hard to carve out zones of influence and economic growth as well.

The goal for US policymakers was to ease a transition to this multipolar world, but without introducing the instabilities that were so often inherent in such complex balancing networks. (Ah, there were the theorems and lessons from those old international relations courses, useful after all.)

Keeping afloat in such a complex international web can be wearying and complicated, as well as costly. By the 2016 election, Donald Trump, masquerading as an economic populist and new-form isolationist “America First” champion – playing upon the fears, uncertainties, resentments, and angers of a significant portion of the US population that saw itself hard done by as a result of the internationalist orientation of the country’s national leaders over the past several decades – could gain political power and then begin to dismantle some of the most advanced elements of that internationalism.

Effectively, when it really counted, the US declined to step up, as it had done several years earlier with Ebola, and then earlier still with HIV/AIDS. And, of course, there has now been little US global leadership on the global economic collapse that has been the extraordinary consequence of the lockdowns imposed to shut down the pandemic.

Down went the six-power nuclear deal with Iran. Gone! Away went the Paris climate accord. Dropped! Dead was the Trans-Pacific Trade Partnership. Boom! Disdain about ties with most other nations save for a couple in the Middle East such as Saudi Arabia and Israel. Pow!

Instead, with this new sheriff in town, there were incessant demands upon Nato nations for more military spending, or else; demands for China to hew to new demands on trade, or else; insistence on traditional allies such as South Korea and Japan to pay more for those alliances, or else. And, of course, there were those charm offensives and a perverse personal obeisance towards Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, and Kim Jong-un, mixing the president’s presumed business acumen and his conman’s show business talents garnered from a reality TV show, The Apprentice, to deliver the goods. Maybe. Or not.

But three years into this administration, rather than aligning US foreign policy to take into cognisance the global shifts above, and thereby tweaking relationships as needed and possible to accord with the new realities, foreign leaders and national populations alike have come to see Donald Trump as an unstable, untrustworthy, ignorant buffoon, rather than someone to be relied upon. But sadly, that disdain is not limited to the man himself. It increasingly is transferring more broadly to the country’s reputation. (See the Pew Research Center, and also this.)

As the most recent Pew report put it, “As has been the case throughout his presidency, U.S. President Donald Trump receives largely negative reviews from publics around the world. Across 32 countries surveyed by Pew Research Center, a median of 64% say they do not have confidence in Trump to do the right thing in world affairs, while just 29% express confidence in the American leader.” Ouch.

But then came the cataclysmic events of the first months of 2020. As the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in central China and then spread throughout the globe, the Trump administration initially brushed off the significance of the development, praised China’s leadership, then did, essentially, nothing to prepare the country for the likely consequences. Crucially, it largely failed to demonstrate any interest in leading the global effort to confront this new danger.

Instead, it eventually chose to blame the Chinese for allowing the virus to go global and chastised (and then worse) the World Health Organisation for being an enabler of Chinese bad behaviour. Globally, nations that would have automatically looked to the US to take leadership in dealing with such a medical emergency found themselves forced to come to grips with it, largely on their own. The lassitude of US governmental leadership has allowed the Chinese to assert a global role as providers of emergency equipment. Additionally, it forced European nations and others to build their own relationships with non-government elements from the US, even as official US was left on its own to deal unevenly with the outbreaks across the American landscape.

Effectively, when it really counted, the US declined to step up, as it had done several years earlier with Ebola, and then earlier still with HIV/AIDS. And, of course, there has now been little US global leadership on the global economic collapse that has been the extraordinary consequence of the lockdowns imposed to shut down the pandemic.

This is why the upcoming presidential election matters so much — and why the temperament of a leader matters so much. Should Donald Trump succeed in gaining re-election, the damage to America’s leadership in the global community may be almost beyond repair. For those who applaud this disintegration of US influence, impact, and leadership, before they cheer too loudly, they might want to examine more deeply the events that followed upon the onset of the Great Depression, in order to see what happened to liberal democracy and the international system as a whole, in the aftermath of the economic collapse. Be careful what you wish for. DM