BOOKS

Excerpt: Paul Adams had a lasting impact on SA cricket far beyond the field of play

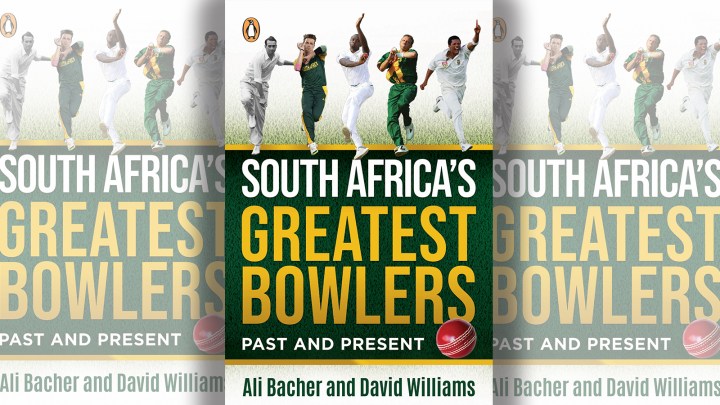

Ahead of what will likely be a crucial third test in the South Africa vs England New Year series, this excerpt from South Africa’s Greatest Bowlers: Past and Present by Ali Bacher and David Williams takes us back to the time when Paul Adams made headlines during another New Year’s test series, 25 short years ago.

International sport places enormous pressure on those who make it to the top. Cricket, arguably, creates more pressure than most games, for two reasons: The margins for error are so small and it is a team game made up of individual contests where there is no place to hide for batsman or bowler. Even the best cricketers go through periods where they perform poorly. Even the most talented and experienced men can lose confidence, sometimes fatally for their careers. In the South African national team in the 1990s and 2000s, there was additional extreme pressure on any selected player who was not white to prove himself worthy of a place in the team – to show that he had not been given an affirmative action free pass.

This was the context for the careers of Paul Adams and Makhaya Ntini. Neither man’s talents were obvious from the beginning, yet they persevered through scepticism and often racist questioning. They made a lasting impact on the South African game and cricket culture, and above all were courageous pioneers for the other black players who came after them. In the story of their remarkable achievements, it must always be remembered that there was a constant extra dimension to the pressure on them – and they were always aware of it.

While Hugh Tayfield remains South Africa’s best-ever spin bowler, Paul Adams is the country’s best-ever left-arm slow bowler. Such an accolade did not seem possible when Adams played his first test against England in December 1995 – even though it was a dramatic start to an international career.

Adams gripped the attention of the cricket world for three reasons: he was just 18, the youngest man ever to play for South Africa; he was only the second player of colour, after Omar Henry, to represent the country; and, above all, there was the spectacle of his astonishing action.

Adams was also small in stature, with the nickname “Gogga” – a slang word for a little insect, drawn from Afrikaans, but also widely used by South African English-speakers. This affectionate nickname was the idea of all-rounder Brian McMillan, when he first saw Adams bowling in the nets at Newlands. So boyish and innocent did Adams look, with a guileless self-confidence and a shy but ready smile, that initially he came across more as the team mascot than an international cricketer.

All this combined to make Adams a rarity and a celebrity: One of those cricketers who become famous far beyond the field of play, among people who otherwise know nothing of cricket and take no interest in it. He also became a folk hero in the coloured community in the Western Cape, and a rallying point – in those early fragile days of democracy and reconciliation – for people who believed South African cricket was resisting racial transformation. They felt he had made it against the odds and that he demonstrated that non-white players could be good enough.

England batsman Mike Gatting likened Adams’s bowling action to the movement of “a frog in a blender”. His action seemed normal until the last stride, when suddenly his head dipped so that he was looking at the ground. As his arm – bent throughout the action – came over, his head twisted up to look at the sky. By all the coaching guidelines, the position of his head as he moved to deliver the ball was everywhere except where it should have been.

Commentators wrestled with language to express what they saw. Batsmen facing him were “hopelessly caught in the blurry glare of the impossible contortion”, said Neil Manthorp. “His head pointed skyward at the moment of delivery, yet he appeared to be able to change his trajectory if the batsman used his feet.” Scyld Berry described him as “bending his head before delivery so that he looked down at the ground, and without any follow-through, he put enormous strain on his right knee”. Colin Bryden described his action as “highly unorthodox and contorted”.

“People think I can’t see the batsman when I bowl, but I can,” Adams said. “When I drop my head, I can still see him in my mind’s eye. It comes from practice. It is not just luck.” Ali recalls that when he first saw Adams bowl, “I just shook my head and walked away”. To complete his extreme unorthodoxy, Adams uniquely gripped the ball with only two digits, his thumb and index finger, which in theory should have meant that he could not control the delivery. Ali describes this technique as “freakish”.

Like so many coloured children raised on the Cape Flats, Adams was born into a cricket-mad family. Endless “test matches” were played in backyards and in the streets.

His unique bowling action was evident as early as the age of five. Only once, when he was 11, did a coach try to advise him to change it. The first time that he saw his extraordinary action for himself was at the age of 15, after his brother filmed him bowling. It was also at that age that he decided to concentrate on spin – until then, he had opened the bowling, with the same contorted action.

He went to the local primary school in Grassy Park, and in his last year was selected for Western Province and SA Primary Schools. (Ashwell Prince, from the Eastern Cape and later selected as a batsman for South Africa, was in the same national school team.) After two years at high school in Grassy Park, Adams moved to Plumstead High School, a traditional cricketing institution which has produced other national players such as fast bowler Stephen Jefferies and all-rounder JP Duminy.

After leaving school, in the winter of 1995, Adams joined the Western Province Academy. He was nurtured there by the head coach, former Springbok all-rounder Eddie Barlow, a respecter of the unorthodox who was also impressed by Adams’s accuracy.

At the start of the 1995–96 season, Adams was picked for Western Province B to play Easterns at Springs. Match figures of five for 129 propelled him straight into the WP senior team the next weekend to play Northerns at Centurion. He took two for 81 and six for 101, and the weekend after that, he was picked for the South Africa ‘A’ side against the touring England team at Kimberley. Few cricketers have progressed so far in the space of three weekends.

The English were most amused by the young man’s bowling action – this was when Gatting made his brilliant “frog in a blender” remark – but Adams had the last laugh. In what was only his third first-class match, he took four English wickets for 65 runs and then five for 116. He played two more provincial matches and was then selected to play for South Africa for the fourth test in Port Elizabeth, starting on Boxing Day 1995. Only three other South Africans since 1945 had played fewer first-class matches before gaining test selection. In his five first-class games, Adams had taken 32 wickets.

The Proteas made 428 in their first innings in PE. England were 88 for two in reply when Adams took his first test wicket – Graham Thorpe for 27, caught by Jonty Rhodes. Then he had England captain Mike Atherton given out caught behind for 72 (though the ball had actually come off the batsman’s thigh – Atherton smashed a chair in disgust when he got back to the dressing room). Adding a tail-end wicket, Adams finished the innings with three for 75 off 37 overs. His total of 13 maidens suggested an unexpected and impressive control of line and length. He was even more economical in the second innings – one for 51 off 28 overs, again with 13 maidens.

The test match was drawn, but Adams had more than justified his selection, while making a broader statement about South African cricket. As Colin Bryden put it, “his presence delighted the most racially mixed crowd of the series, which included the St George’s Park brass band, who played loud and lively music throughout the match”. Scyld Berry noted that, despite being just 18 and receiving negative criticism of his action, Adams “was not overawed and his impact on the imagination was also profound. He was not only a left-arm wrist-spinner who rapidly extended his range from a stock googly to a quicker Chinaman; he also heightened the interest in cricket which had traditionally existed in the Cape coloured community, as it had among the Indians of Natal”.

After four draws, the test series culminated in Cape Town. In the early afternoon of the second day, the stalemate seemed set to endure. Replying to England’s 153 all out (Adams took two for 52, including number three batsman Robin Smith), South Africa were battling at 171 for nine, just 18 runs ahead. When he came to the wicket, Adams had faced only 16 balls in his entire first-class career – and the English bowlers had just taken the new ball.

Adams surprised everyone with his batting, which was greeted with amusement that turned to admiration. “After a tentative beginning,” wrote Matthew Engel for Wisden, “helped by four overthrows, eight leg-byes and a Chinese cut, Adams was soon playing impetuously, and then imperiously. Devon Malcolm, the man who had destroyed South Africa in the final test of the teams’ previous series, performed ineptly and appeared to bowl himself out of test cricket. The consequences of this one hour’s play were immense. England’s morale fell to pieces.”

Adams stayed at the crease for 38 balls and scored 29. With Dave Richardson (54 not out), he put on 73 precious runs for the last wicket, easily the biggest partnership of a match played on a tricky pitch. This was the stand that turned the contest in the Proteas’ favour. England stumbled to 157 all out (Adams two for 53) and South Africa won the match by 10 wickets and the series 1-0.

As was often the case with Adams, there was a broader significance to the Newlands test. On the first morning, a special presentation was made to Basil D’Oliveira, who had left the country in the 1960s to pursue his career in England. The symbolism was weighty. As a coloured man, D’Oliveira’s cricket career had reached a dead-end in South Africa because of apartheid. His inclusion in the 1968–69 England team to visit South Africa was objected to by the National Party government, and the English cancelled the tour, leading within two years to South Africa’s complete isolation from international cricket. Now D’Oliveira was present to watch the first England team to tour the country since 1965; and he was able to see Adams, a young man from his old community and his old club, St Augustine’s, help a non-racial South African team to victory. ML

To read about the Newlands test, and for more on South Africa’s best bowlers, see Bacher and Williams’ book, South Africa’s Greatest Bowlers: Past and Present (Penguin Random House, R260.)

Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts! – daily.