MAVERICK LIFE – BOOKS

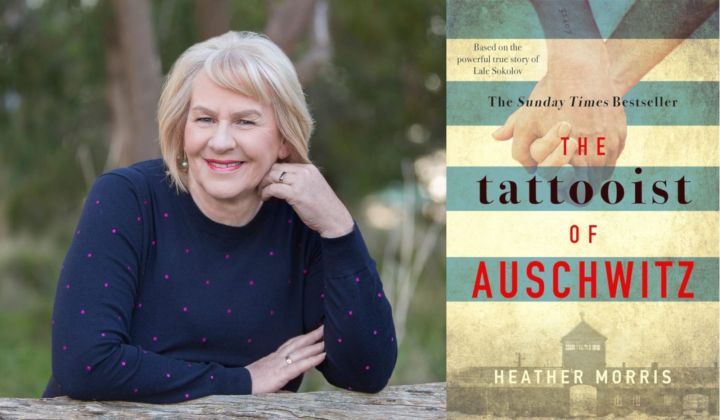

Maverick Life Exclusive: Interview with Tattooist of Auschwitz author Heather Morris

International bestselling author Heather Morris recently toured South Africa with her debut novel, The Tattooist of Auschwitz, of which Jeffrey Archer says, ‘They will be reading this book in 100 years time.’ In this exclusive interview, Morris reveals new stories about her subject – the real tattooist of Auschwitz, Lale Sokolov – and talks about her book.

The Reading List: How did you come to tell Lale Sokolov’s story?

Heather Morris: Well, like I’m sitting down with you, I agreed to catch up with a friend who I hadn’t seen for many months, and she casually said to me when we were having a coffee one Sunday afternoon, “I have a friend whose mother has just died, and his father has asked him to find someone to tell a story to. That person can’t be Jewish.” My friend was Jewish and she said, “You’re not Jewish, do you want to meet him?” I said, “What’s the story?” and she said, “I have no idea.” I said, “Oh well, never mind, I’ll meet him anyway.” A week later I knocked on the apartment door of Lale – as simple as that.

TRL: Why didn’t he want someone Jewish to tell his story?

HM: Ah, he was very clear on that. His son [Gary Sokolov] had brought many people to meet him already who were journalists and qualified to write. They were Jewish, they were Gary’s friends, and he turned them away. He said, “No, I want somebody who doesn’t have any of their own family stories and no connection to the Holocaust.” He couldn’t imagine there was a Jewish person alive anywhere that wouldn’t have been touched by the Holocaust.

TRL: Sokolov was born Ludwig Eisenberg on 28 October 1916. Why did he choose you to tell his and Gita Fuhrmannova’s tale?

HM: I met him and we sat and talked for two hours. Well, I should say he did the talking; I just listened. After about two hours I had to say to him, “Before we go any further can I just tell you my mother’s maiden name? It’s Schwartfeger.” And he went, “That’s German,” and I said, “Yes,” and he said, “Okay, we can’t choose our parents.” He said, “Will you come back and see me?” and I said, “Yes.”

He kept talking and I kept listening. I never wrote a thing down, I never recorded anything. I just had to rush home and try and remember what he had said. Being 87 and so grief-stricken, his concentration initially was really poor because he was just rambling.

Of course straight-up, he’d told me about Gita. That’s the story he wanted told – about this girl whose arm he held; head shaven, dressed in rags. He was telling me, 60 years later, how he looked into her eyes and knew in that second he would never love another.

He so badly wanted his story told, for two reasons. He wanted the world to know about this girl he loved who was lovely and just beautiful; he would often clutch a photo of her to his chest while we were talking. And he hoped that if he told his story it wouldn’t happen again.

TRL: Why did you choose to write the story as a novel instead of a memoir or narrative non-fiction?

HM: For 12 years it was a screenplay. When the publisher said to me they had agreed that I could have a go at writing it, they said it should be a memoir. I went to memoir school for a day – it was a five-day course – and I knew after the first day that I couldn’t tell the story the way they were telling me I had to. To write a memoir I could only write about what Lale had personally seen and witnessed and experienced. I couldn’t include Gita and the girls’ block, because that’s not his memory. I could not have dialogue; I could not create the conversations that I had already created, based on what he had told me, in the screenplay. I could not weave together the story of him and Gita into the timeline that was the Holocaust. I was restricted and it just wasn’t working for me. There is one instance in the book where I put them together when they weren’t and that was when the Allied planes flew overhead. That was my one-and-only made-up incident, but it works for me. I have no qualms about the style I chose to write it, because I think it makes it more readable, particularly to people who are not Jewish and who just want to understand this time. And with just over three million copies sold in English-speaking countries at the moment, I think it’s reaching its audience. It has been translated into 43 languages and it’s been published in 50 countries.

TRL: How did you go about crafting the tale, gathering information, sifting through the research?

HM: I was with him for three years before he died and I had a draft of the screenplay in about 12 months. That’s how long it took because I didn’t rush him. I just let him tell all the stories and he’d repeat them many times, sometimes in a different way so I’d have to sift through and check with him. I did my own research which was probably not very professional. After about a year and a half, I approached a film production company in Melbourne with my screenplay and they grabbed it. They optioned it off me for three years and at that time up until Lale died they [the producers and directors] were working with me and with him trying to get this screenplay financed. Film Victoria in Australia funded for it to be researched professionally in Europe, so they paid a large sum of money to engage professional researchers and they were able to find as many documents as they could that confirmed what he had said. Everything he’d told me about him, Gita and Cilka was true.

TRL: How did his time in Auschwitz (almost three years) affect the rest of his life?

HM: Over three years I could ask him many of these questions in many different ways but in terms of how it impacted him the most, he always came back with: “It made me tolerant to people with differences, it made me accept that we’re all the same.” He lived with a Gypsy [Romani] family and he would say so clearly: “It does not matter what country you come from, what religion you are, and the colour of your skin … when we get shot, we all bleed the same colour, red.” And he was expecting to get shot every day and even at 88 years of age, he still phrased it like that, “when you get shot”, like he was still expecting it.

TRL: The Romani family’s death really affected him.

HM: It took him nearly 12 months before he would really talk to me about that. It was so painful for him. Gita didn’t understand it and that didn’t help. She couldn’t understand why he was upset over the death of four-and-a-half thousand Gypsy people when Jewish people were being killed in the tens of thousands. He said she never understood and that was one point when he was probably at his lowest in Birkenau [the camp was also known as Auschwitz II], where it happened. He said, “She couldn’t understand how I could be so connected to another race of people and feel so strongly …” But Gita did eventually get it. She came home one day and gave him a picture of this Gypsy lady, and when they had to flee from Slovakia she insisted on taking it. He didn’t want to, because they didn’t have room for it, but she took it and it still hangs in his son’s lounge.

TRL: After leaving the atrocities of Auschwitz behind, why did they again have to flee Slovakia?

HM: He got into trouble in Slovakia and was thrown into prison and Gita had to then arrange his escape. She bribed a judge and a Catholic priest and a psychiatrist.

Lale was put in jail because he and other successful Jews were smuggling money out of the country, arming and funding the army of the people in Israel. They [the government] had cleaned out all her bank accounts and kicked her out of her apartment and everything they had was confiscated, and she went to stay with friends. They had hidden money, different currencies, jewels and gems, so she bribed this judge and they decided they had to get him out of there. Who can we send in to talk to him? A Catholic priest! Lale said, “I’m sitting in my cell and they come and tell me there’s a Catholic priest here to see you, and I say go away, I don’t want to see a Catholic priest. I’m Jewish!” He had to come back three times before Lale finally went, “All right, I’ll see him”, and finally sat down with this Catholic priest. Then the Catholic priest said to the guard in the room, “I need to hear his confession, can you please leave?” Slovakia was predominantly a Catholic country and they totally respected their privacy. It was at that point that the priest said to him, “Your wife has sent me here. We have got a plan to have a psychiatrist see you but you need to start going crazy.” And so, they told him what he had to do and he started going mad. It took two or three weeks of a hunger strike and talking in different languages, and the prison authorities got very worried and called a psychiatrist in to see him – the psychiatrist Gita had bribed – and he said, “Look, he’s going to go really mad unless we give him a weekend’s leave. He needs to go home.” He was given a weekend’s leave and that first night they were smuggled out in the false wall of a truck taking produce to Vienna.

TRL: Did Lale ever see the manuscript and how did he respond?

HM: He never saw the manuscript, but he saw many drafts of the screenplay and he loved it. He would flip through the pages and go, “My name, Gita’s name; my name, Gita’s name!” And of course, he read it more thoroughly and signed off on it. If anything, he got cranky with me that there were a few storylines that weren’t in it that he wanted in. They were significant storylines that I couldn’t find a second piece of evidence for. I now have that second piece of evidence because people in other countries would contact me after the book and give it to me.

One storyline was quite significant and Lale would ask, “Why haven’t you got Mordowicz in here? I want you to tell about Mordowicz and what I did with him.” And I’d say, “Lale I can’t, I haven’t got a second piece of proof.” And then about six months ago I got an email from a reporter in Toronto in Canada who said, “I’m writing a belated obituary for a man called Czeslaw Mordowicz. My man spoke about your man; did your man talk about mine?” And I just wrote back, “Hell yeah.” So we started communicating and he sent me the testimony of this man which more than supported what Lale wanted me to tell. The reason I didn’t tell the story was that this man Mordowicz and three others wrote the document that’s called “The Auschwitz Protocol”.

Mordowicz was an 18-year-old boy who had escaped from Birkenau. He got captured because he had a tattooed number on his arm and got brought back to Birkenau. He even tried to chew his own number off and he came to Lale distressed saying, “You’ve got to help me, I’m in trouble, can you make my number look better?” It was a mess and infected and Lale said, “There’s nothing I can do, you know you’re going to be hung.” That’s what they did to people who even tried to escape, never mind was successful, and he was really distraught and wouldn’t let Lale go. And Lale said, “There’s only one thing I can do to help you, but you’ve got to escape again.” And so he changed the number – this horrible, puss-filled number – as best he could into a rose. Several prisoners helped Mordowicz escape again, along with another man called Arnost [Rosin], and these two boys made their way to Slovakia and they met up with two others [Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler] who had escaped a couple of weeks earlier. They wrote this document, “The Auschwitz Protocol”, which outlined what was happening in Auschwitz and Birkenau. That document got smuggled out to Switzerland and then to Washington and London. It was June, 1944, and at that time 10,000 Jewish men, women and children a day were taken from Budapest to Auschwitz.

“So many,” Lale said, “we stopped doing the numbering, the tattooing.” President Roosevelt from Washington apparently sent a message to the president of Hungary, “You will stop those transportations.” He did and 170,000 Jewish men, women and children never went to Auschwitz, because of this document. And so I get these details and Mordowicz’s testimony where he says all what Lale did for him and a photo of him holding his arm out with the rose on it, and there was my story. But Lale had, of course, died by then, I only got that information last year.

TRL: What more can you tell us about Lale the tattooist?

Last year I went to Auschwitz for the first time and I was there with an event called March of the Living, it’s an annual event when thousands of young Jewish students go there for a week to learn about the Holocaust. Just as we were leaving, the students were so traumatised; many of them were weeping and comforting each other. Back on the bus, a rabbi got up and said, “I want to tell you a story.” Before he came here he went to visit two ladies in his congregation who had been girls in Auschwitz and they had tattooed numbers. He said, “While I was talking to them, I realised that they were always playing with the number on their arms, and I said to them: What do you remember about being tattooed? Was it painful?” And my ears are well and truly pricked up at this. He said you’d think he’d given them that question in advance, because they both answered in the same way: “I don’t remember if it hurt. What I remember is the man who did it and how he kept saying I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I’m so sorry I’m hurting you.” The very words Lale had said to me that he whispered to all the girls.

TRL: Thank you for sharing your story with us.

HM: You are very welcome. ML

Visit The Reading List at readinglist.click for South African book news, daily.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider