ACCORD/DISCORD

Iran’s Revolution, Forty Years On

February 11 marked the 40th anniversary of the Iranian revolution that decisively ended the country’s monarchy and installed a theocratic government. The end of the Iran and US partnership has reshaped the Middle Eastern political landscape.

On the 40th anniversary of the end of the shah’s regime in Iran, the AP reported:

“Waving Iranian flags, chanting ‘Death to America’ and burning U.S. and Israeli flags, hundreds of thousands of people poured out onto the streets across Iran on Monday, marking the date that’s considered victory day in the country’s 1979 Islamic Revolution. On Feb. 11 that year, Iran’s military stood down after days of street battles, allowing the revolutionaries to sweep across the country while the government of U.S.-backed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi resigned and the Islamic Republic was born.

“In Tehran, despite the rain, crowds streamed in from the capital’s far-flung neighbourhoods to mass in the central Azadi, or Freedom, Square, waving Iranian flags and chanting ‘Death to America’ — standard fare at rallies across Iran. Chants of ‘Death to Israel’ and ‘Death to Britain’ followed, and demonstrators burned U.S. and Israeli flags. Iranian state TV, which said millions participated in the celebrations, ran archive footage of the days of the uprising and played revolutionary songs. It later broadcast footage showing crowds across the country of 80 million.”

But there was a time when the US and Iran seemed to be the best of friends and were in a partnership designed to oversee the better part of the Middle East. Once an independent-minded, troublesome person like then-prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh had been forcibly escorted from office in 1953, the friendship between the two nations had blossomed. American president after president lauded efforts by the ruler of Iran, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, to modernise his nation, to break the shackles of religious obscurantism that held the country back, to industrialise and exploit its abundant oil and natural gas revenues and resources, and to create a modern middle class of educated, consumer-oriented Iranians.

If some hard knuckles had to be used by the police, the military and Savak (the country’s feared intelligence services), well, as the famous phrase goes, you can’t make a really tasty and nutritious omelette without breaking at least a few eggs. Unfortunately, this culinary masterpiece also failed to take into consideration the crucial roles of religion and history, as well as the predictable impact of the allure of rising expectations both economically and politically.

Let’s begin with history. Iran, or Persia before the middle of the 20th century on most maps, was a major power in the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East for nearly 2,000 years. Persian empire after empire ruled the roost, regardless of whether it was founded on the religious doctrines of Mithraism or Islam. Throughout all those centuries, ancient Iran/Persia has had vast influence and impact on the Romans and Byzantines, as well as all the other states to the east and north of it.

A colleague, friend, and mentor of the author – and someone who was a great admirer of Iran’s civilisation – once explained that all Iranians, regardless of their political and economic persuasions, have great admiration for their national civilisation’s history and its achievements. They believe it will again become a great nation among the world’s pre-eminent nations. Beyond everything else that happened, that psychological dimension and the slights modern Iranians have suffered at the hands of others have had an impact on how Iranians have perceived their relationship with the US in the past, now, and on into the future.

Under the shah, much of the oil and gas money went into the modernisation of the capital city (along with the usual diversions to the well connected), the purchase of armouries of modern weaponry, and the creation or expansion of university educational facilities and support for the overseas study. By contrast, in the countryside, the shah’s government created enduring resentments among the devout and the clergy by breaking up the estates and landholdings of that clergy in the 1980s. Meanwhile, the expectations of the burgeoning student population could never be totally fulfilled. The importation of radical economic and political ideas continued inevitably, the growing gap between the connected, the well-to-do, and those who had a share in the new wealth versus the more traditional, the poor and the rural populations continued to grow as well.

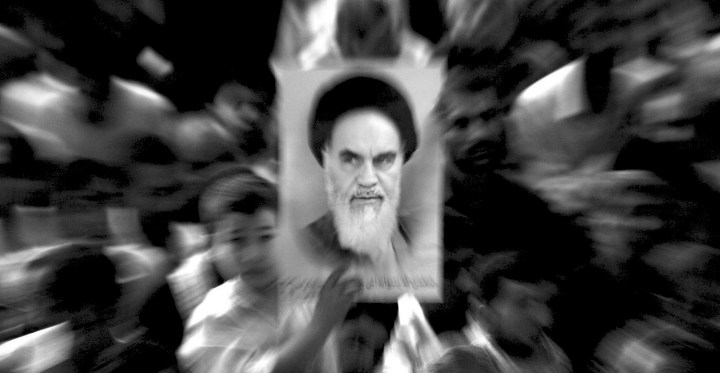

By the late 1970s, a leading cleric, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (the prime opponent of the shah and all he stood for), who had by then been in exile in Iraq for years, fled the region for a safer exile in France. In the midst of a growing national rising, the Ayatollah returned to Iran on 1 February 1979, receiving a rapturous reception. Ten days later, the declaration of neutrality of Iranian troops on 11 February 1979 and their return to the barracks inevitably doomed Prime Minister Shahpour Bakhtiar’s already tottering government.

The unrest in the capital had originally been initiated by radical student groups, and continued to grow stronger as a result of the increasingly repressive efforts by security forces to rein it in. But in the growing chaos of this revolt against the shah’s government, religious fundamentalists gained the upper hand over all the other regime opponents, and then against the regime itself. They proclaimed a strongly religiously inflected government in March 1979, following a national referendum. The Shah had previously fled the country a month earlier, dying abroad, but not before his lingering presence had one more effect.

Amid all the confusion, a mob of students had seized the American Embassy on 4 November 1980, demanding the extradition of the deposed – and now dying – shah back from the US. After their takeover, they held dozens of American diplomats as hostages for more than a year (an earlier embassy occupation had been brought to an end by guards loyal to the ayatollahs). The hostages only gained their release just as President Jimmy Carter departed office and to be succeeded by the newly elected Ronald Reagan. (A US military raid launched to free the hostages had aborted after arriving inside Iran following equipment failures and deaths among the rescuers. The collapse of the rescue effort similarly doomed Carter’s chances in the election.) Soon after all of this, a vicious, nine-year-long Iran-Iraq conflict broke out, with the US in the unlikely role of cheering on (and even assisting to some degree) Iraqi forces.

One consequence from all this sturm und drang was the increasing fear among American officials that militant Islam was now on the march across the entirety of the Islamic world.

This, in turn, led to the author’s own exploration of the possibilities of such a thing occurring in the world’s largest Islamic nation, as well as some outrageous emergency drills we were subjected to as diplomats in places like Indonesia. (Read them here and here.)

In the years that have followed, the Iranians began testing a series of increasingly powerful, increasingly longer-range rockets, capable of covering the entire Middle East, and apparently embarking on a nuclear development programme that could be suitable for the creation of a device that would be delivered by those missiles. In addition, demonstrating an effort to be a dominant player strategically, the Iranians have supported the Houthi rebels in Yemen, dispatched heavily armed Quds Force militia fighters to Syria to aid Bashar al-Assad’s beleaguered government and to indicate a desire to counterbalance – or more, perhaps – Israeli military dominance in this volatile area.

On the other hand, the increasing pressures of targeted but extensive economic and financial sanctions by the US and other western nations ultimately led the Iranian government to agree to an accord that brought together the US, UK, Germany, France, China, and Russia – with Iran – to set up a control mechanism and close monitoring of Iranian nuclear research and development, in exchange for the gradual rollback of sanctions, the reopening of trade relations and the repayment of blocked funds on deposit in the US.

Lauded as one of the big achievements of the Obama administration, Donald Trump campaigned against it vociferously in the 2016 election, deriding it as deeply flawed by virtue of its failure to control missile technology or to limit any dispatch of Quds Force fighters. Once he became president, Trump withdrew American participation in the accord, although various international monitoring bodies have continued to declare Iran’s compliance with the control regimen and other western nations have continued to look for workarounds to allow trade expansion opportunities.

By this point, the enmity between the US and Iran has become a nearly fixed point in a dramatically changed Middle East landscape. In the 1970s, the virtual alliance between Iran and the US, the US and Israel, and an actual alliance between the US and Turkey could largely govern most circumstances in a broad aspect.

But since the collapse of the shah’s regime and his replacement by a theocratic state, the changes in the region from the wave of uprisings in the Arab Spring, the ongoing chaos in Syria, the emergence of Saudi Arabia as an active military player – and the still-unstable regime in Iraq following years of internal fighting after the 2003 invasion by the US on the hunt for the elusive and largely imaginary weapons of mass destruction – have all created a very different Middle East.

Aside from everything else, the continuing hostility between Iran and the US remains, seemingly locked in antagonism, and now seemingly set in concrete. DM

Read this chronology of the events of the Iranian revolution.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider