Maverick Life

Curatorially speaking: Here’s how to start your very own art collection

The buzz around contemporary African art has exploded over the last two decades, and so have the opportunities to get into the game and start building your own art collection. Where to begin? Who should you speak to? How do you decide what to invest in?

“If it’s your first time at an art fair, don’t be in a rush to buy. Go to the opening night, enjoy it, have your Champagne (and) come back the next day,” says Kabelo Malatsie. Only then, she says, you might stroll through the fair, look at what sparks interest and what you respond to. It’s about what’s happening inside, what emotions you feel. “Buy the books, educate yourself and look at what you like in art.”

The 15-17 February marks the 7th edition of the annual Cape Town Investec Art Fair; a prominent gathering of art enthusiasts, artists, galleries, and collectors from all over the world who will descend on the Cape Town International Convention Centre for three days of art viewing, art shopping, art talks, and mingling.

Following Cape Town, the 1-54 Contemporary Art Fair, which has editions in London, New York, and Marrakesh, will be hosting the Moroccan edition from the 21-24 February. Founded just over five years ago, in 2013, and named to reference the number of African countries, 1-54 has grown to be “the leading international art fair dedicated to contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora”. And in September, the annual FNB Joburg Art Fair will celebrate its 12th edition.

Although art fairs are primarily a market place, they also provide a moment to show face, keep up with what is happening in the art world, and even spark informal business conversations. There is no doubt about the growth in interest in African art over the last two decades: 2017 saw the opening of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA) in Cape Town to much fanfare and global attention, followed shortly in 2018 by another massive art institution out in Steenberg, the Norval Foundation, billed as “a centre for art and cultural expression, dedicated to the research and exhibition of 20th and 21st-Century visual art from South Africa and beyond”. Further up on the continent: ART X Lagos is West Africa’s premier international art fair, and a new museum is set to open this year: the Shyllon Museum, located at the Pan-Atlantic University in Lagos.

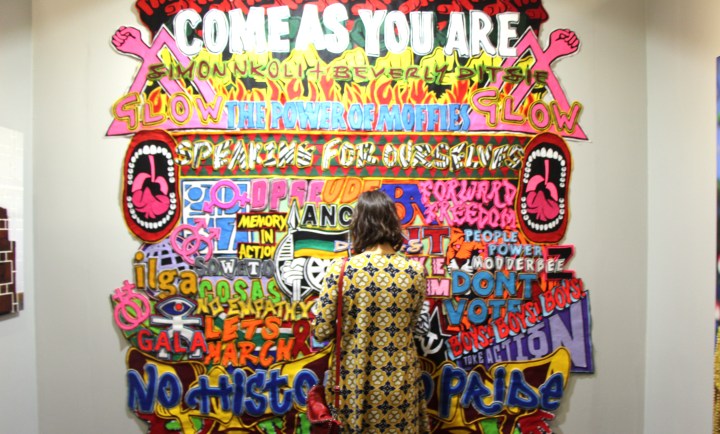

With local art schools producing hundreds of art graduates each year, and many African artists continuing to gain recognition on the local as well as the international art scene, the interest in African art looks set for even more growth. Yet the field is still often viewed as elitist and intimidating. How does one start their own art collection? Is it about what looks good in one’s house or about investment? How does one make that first step into becoming an art collector?

* * *

Malatsie is the current director of VANSA (Visual Arts Network of South Africa), and former associate and curator at the Stevenson Gallery. She also holds an Honours degree in curatorship, as well as a Masters in Art History. She certainly knows about art. “Buying art is a journey. If you don’t have deep pockets, you should first understand why you’re buying art: are you buying it because you think you can make more money? Or are you buying it purely because you love the work?” In a way, it is a similar process to buying clothes: if the budget allows, you might go straight for haute couture. But generally, you might start with simple designer pieces and build your wardrobe slowly. In the end, it will not only reflect what you love but also who you are.

Much like any other project people embark on, it is about the journey more than the destination. Looking at the landscape and what sparks curiosity and interest is crucial. “Go to exhibitions, as many exhibitions as possible. We have many art schools, where it’s not necessarily a buying scene; the (artists) are young, they may be relatable and the process might be more relaxed than at commercial galleries.” There are also plenty smaller exhibitions to be attended: “Things that the art world might frown upon, like First Thursdays, are great places to actually check art.” And then, there are national public spaces that might have their own challenges. Still, the South African National Gallery in Cape Town and the Johannesburg Art Gallery have important collections, both permanent and temporary, where to educate one’s eye. “People should go to bookshops and read. Even some established collectors still have limited knowledge of South African art history.” And knowledge gives us a sense of where we are coming from, says Malatsie, and what artists are drawing inspiration from.

That certainly doesn’t mean that commercial gallery spaces are off-bounds to new collectors. “Although sometimes when you come into the galleries, the assistants might give you the impression that you’re a hindrance to their coolness or whatever they’re busy doing. Actually their job is to be there as a representative for the artist, to educate you, the buyer, the client or the visitor about whatever you have questions about,” says Ashleigh MacLean, a director at WHATIFTHEWORLD gallery, who joined the gallery just over a decade ago at its launch as a curator, shortly after completing her studies at UCT’s Michaelis School of Fine Art. “I think that, as a first-time buyer, don’t just sit down with the first gallery that you meet, go to a number of galleries, tell them you’re a first-time buyer, ask them to tell you a bit about their artists and their programmes. You’ll gauge very quickly the type of people that they are, and the type of work that they’re doing. This business is also very much about relationships, and you need a good gallery on your side who can guide you in the right direction,” she adds.

At the very beginning, WHATIFTHEWORLD focused entirely on first-time collectors, and as a young gallery, they primarily represented young artists. A decade later, some of those first-time collectors have grown with the gallery, as have the artists and the value of their work. “One of the artists who first exhibited with our gallery was Michael Taylor. At the time, we were selling very small artworks; he didn’t work on the scale that he works at now. We were selling those drawings for about a R1,000, now the large-scale drawings are selling for about…I would say between R75,000 and R80,000. In that time, some of the collectors who started collecting with the gallery while they were still university students, have continued to buy work from their favourite artists as the prices increased,” says MacLean.

* * *

Don’t buy art because it’s trendy, or to match your furniture. Buying art is a commitment. Whether someone is interested in the latest socio-political conversations and looks at art that reflects and comments on the current affairs, or simply to start a private collection only based on individual taste, buying art does require research, dedication, and even some level of risk-taking. “This is not an exact science. Generally, it’s an emotional decision. And it should be an emotional decision because the artwork is something that should appeal to your sort of spiritual side, something that should evoke some kind of visceral reaction in you. You’re not going to get this right first time every time. It’s a little bit about trial and error, which is why I think first-time buyers should perhaps move in the direction of an investment collection over time. But for your first piece, it should be for love,” adds MacLean.

This is a sentiment Malatsie agrees with: “Even if nobody has written about it and you think it’s hot, buy it,” she says. Then, what of the investment and returns game? “I think buying art for investment is… Dangerous. It tends to be very speculative.” Indeed, the increase in the value of an artwork is often closely linked to what has been written about it, about the artist, and what exhibitions the work or the artist has been part of. Being able to speculate on the potential of a work to increase in value comes with time and research.

Malatsie suggests a different way of looking at art investment: “The investment shouldn’t be on the work for you to flip, but rather about investing in people. Are you saying that this artist has something? Are you giving them the nod, by buying, so that they can continue doing what they are doing? And even if the work bought might not be where it should be, the investment might give the artist time to improve, gather better and higher quality tools and materials, and hope. So rather than investing in objects, let’s invest in people.” ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider