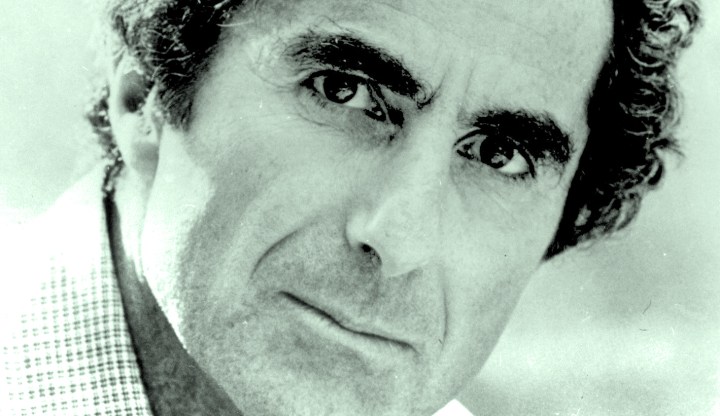

Philip Roth (1933-2018)

Goodbye Colossus: The Gripes of Roth Now Stilled

One of America's most prolific authors, and a perennial author named as being in contention for a Nobel Prize, Philip Roth, passed away this week. The following is an appreciation of his work and a nod towards some of his literary brawls.

The Nobel Literature Prize will not be given this year, reportedly because of a sexual harassment scandal within the secretive Swedish Academy that dishes out the goodies, in line with Alfred Nobel’s bequest. This circumstance would almost certainly have amused (and angered) Philip Roth – and it might even have found its way into a novel by him, had it come along a decade earlier.

However, while Roth has been a perennial contender over the decades for this world-beater of a gong, he won’t be getting the prestigious (and financially rewarding) prize this year because of that stand-off in the Swedish Academy. Moreover, now he will never be in contention for one in the future either. This is because the rules dictate that the winner must be a living author whose work best embodies an “ideal direction” – and Roth passed away earlier in the week. The astonishment at his failure to be recognised earlier for his vast body of extraordinary work poking hard at the human condition becomes even clearer as Roth has joined the company, just for starters, of such deceased writers as Leo Tolstoy, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, and George Orwell – not to mention fellow American John Updike.

Roth passed away after an enormously fecund creative life, as well as an exceptionally contentious one in which he had been accused, variously, of being a self-hating Jew, a misogynist, and a man consumed with his genitals. The self-hatred he would have denied, the misogyny has been increasingly dismissed by feminists who might earlier have argued for just that proposition some years earlier. But the final charge Roth might have embraced in some form, given his preoccupation, dread and fascination with human frailty and the inevitability of decay.

And, of course, all of this came in addition to his astonishing way with words. Beyond the force of his writing, Roth was also known for his written-about feuds with a former wife, Claire Bloom (her memoirs versus his use of a character in his writing who was a lightly disguised version of her), as well as in print arguments with the highly influential socialist/Jewish/agnostic writer/editor, Irving Howe.

In his eight and a half decades, before he “retired” from writing some five years earlier at a widely attended public event, Roth completed dozens of novels, as well as short stories, novellas, essays and other bits of critical commentary and writing. While many readers have their favourites from the Rothian ouvre, four books have stood out for me as special peaks from among his vast output – Goodbye Columbus, Portnoy’s Complaint, The Plot Against America and The Human Stain.

The novella, Goodbye Columbus, first appeared in 1959 (!) in The Paris Review and it was quickly republished in book form along with five other short stories by the author. In the novella, a young working-class Jewish man with intellectual or literary dreams becomes enamoured of and eventually gains a sexual relationship with a beautiful but intellectually vapid young woman (in South Africa, a kugel; in America, a Jewish American Princess) whose consumerist-driven middle-class family stands for everything the protagonist seems to hate.

With its arrival, it was like a meteor across the heavens, announcing the arrival of a young literary voice very different from the likes of Saul Bellow or even a rough contemporary like JD Salinger. But if the novella disturbed some, another story in the collection, The Defender of the Faith, metaphorically set the barn on fire. In it, a thoroughly assimilated Jewish sergeant in the army finds himself in a contest of wills with a new recruit who is a deeply Orthodox co-religionist who is perfectly willing to connive his way into inveigling privileges from his sergeant. This story set in motion the rap by many critics that Roth was just another one of those self-hating Jews eager to ingratiate himself with the WASP establishment – or something still worse.

The next novel, Portnoy’s Complaint, was a rollickingly funny, no-holds-barred account of male sexuality and an inability to connect with women, but seen through a particular fascination with masturbation. With this book, Roth established himself as a writer who would cross any frontier left in literature if he so chose. Denounced by numerous critics and religious figures as a book whose predominant theme was a bridge too far, it delighted many more who read it, and who stayed with Alex Portnoy’s plight to the end. The book was actually written as if it were a long apologia on the psychiatrist’s couch, something that becomes abundantly clear when the German inflected listener-shrink turns towards Portnoy and says,”and now let us to begin” – as if to say, “okay, playtime is over; let us get to the root of your problems”.

In the years that followed, a veritable torrent of other novels came forth. The Human Stain described the downward spiral of English professor Coleman Silk at a small New England college where he is effectively hounded out of his job for calling two female African-American students “the spooks” (ghosts, apparitions) because of their rare classroom appearances. Spooks can, of course, also be read as a derogatory word for blacks. With the connivance of a virago of a colleague, Silk loses his job, his wife dies from mortification, and Silk effectively turns into a hermit who takes up an affair with an effectively illiterate campus cleaning woman. No good can come from all this, and it does not. But it is one hell of a literary ride, especially once it becomes clear that Silk is himself a light-skinned black man who had been passing for white his entire academic and professional career.

And then there is The Plot Against America, a deeply disturbing, dystopian novel of 1940s America when a quasi-fascist regime takes power through the election of isolationist flying hero and Hitler-admirer Charles Lindbergh. It is an angry tour-de-force of a novel that mixes real characters such as Lindbergh and a fictitious slate of ordinary people.

And the literary excitement of the work is that the whole story is told – convincingly – through the eyes of a prepubescent Jewish boy whose lower middle class family in Newark, New Jersey is increasingly harassed and hemmed in by the racist regime now in power. The novel has much in common with Sinclair Lewis’ 1938 novel, It Can’t Happen Here, but Roth’s is a darker and angrier book – and a more realistic one, especially when it can be read as an alarm bell for the coming nightmare of Donald Trump.

Throughout much of Roth’s work, there is one surprising thread he returned to again and again – the limited but warm, intimate embrace of his old neighbourhood in Newark. Newark is a city that is only a short distance from the much larger New York City, but, seemingly, Newark was a world away from the Manhattan literary world Roth eventually subdued and conquered. And he never forgot his home town.

Roth’s passing helps make the case that Nobel Literature Prizes really need a second category, just like the US baseball hall of fame where a veterans’ committee takes a second look at great names cruelly overlooked by the secretive committee that makes the final selections. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider