World

Op-Ed: Tony Judt, a historian who asked the right questions – what would he make of us now?

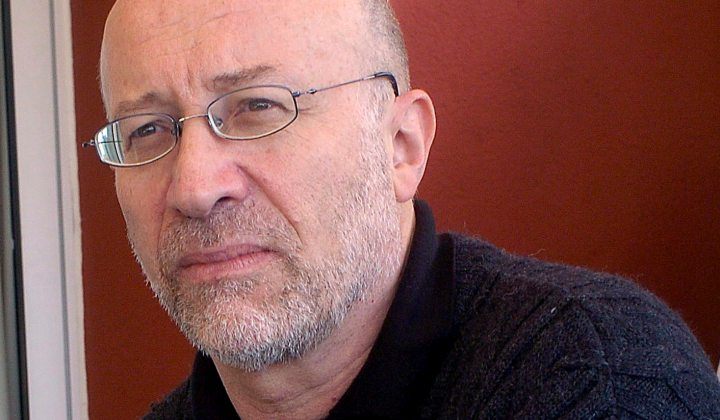

The surge in works that explore “what went wrong” in the state of Western democracy leads me to wonder what the late British historian Tony Judt would make of our current state of affairs. The question is more than simply an exercise in postulating what a great thinker would make of a chaotic world. By TODD JOHNSON.

To the reader of any global newspaper that devotes attention to book reviews touching on politics, history, and political economy, it seems that rarely a month can pass without the release of a work offering a bleak prognosis on the state of Western democracy, equitable economic growth, and cultural life.

While I wish I could say that these prognostications were overdone, the evidence of deep structural headwinds in America and the EU seems incontrovertible. From the rise of extremist politics to opioid addiction to income inequality, the challenges are stark. Edward Luce’s The End of Western Liberalism is one of the finest of the recent titles exploring these fissures, while Zadie Smith’s brilliantly polemical essay Fences offers a powerful exploration of the drivers behind the Brexit vote. If there is a unifying thread among the work of Luce, Smith, and other public commentators like David Brooks and Tyler Cowen, it is a conspicuous effort to go beyond the baying, zero-sum analysis that characterises the 24-hours news cycle and instead offer an unvarnished critique across the ideological landscape.

The surge in works that explore “what went wrong” leads me to wonder what the late British historian Tony Judt would make of our current state of affairs. The question is more than simply an exercise in postulating what a great thinker would make of a chaotic world. I personally credit Judt’s analytic frameworks for guiding my own thinking through core issues of modern history and their relevance today. In an African context, his 2005 Postwar – although a history of post-World War ll Europe, offers a remarkable how-to guide of how transformational political leadership can overcome even the most destructive of events. Leaders across the continent could surely draw lessons in managing conflict ravaged economies, crumbling infrastructure, and extremist political forces.

Prior to his tragically early death in 2010 at the age of 62 from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig’s disease, Judt had earned a place as one of the world’s most respected analysts of Europe. More broadly, he was a genuine polymath able to dissect topics as diverse as the perceived failings of contemporary US foreign policy and the self-deception of 20th century French intellectuals enamored with Stalin. He distilled deeply complex issues into digestible analysis characterised by trenchant criticism across ideologies with a vivid and frequently humorous turn-of-phrase.

Judt’s politics were avowedly social democratic, yet he regularly took to task those on the left. He was scathing in his critiques of the identity politics that he felt were deeply corrosive to American life, particularly in the university environment (the most productive years of Judt’s working life were spent at New York University). Judt also suffered the condemnation of many of his fellow Jews when he openly lambasted Israeli policy toward the Palestinians. For Judt, there were no sacred cows.

My first exposure to Judt came not through his books (those came later), but through his appearances in the mid-2000s on the American interview programme Charlie Rose. I was immediately taken by the thoughtfulness and clarity of Judt’s remarks, his lack of bombast, and a worldview that held no allegiance to political party affiliation but rather fidelity to historical truth and a distrust of dogma.

I recommend Judt’s 2008 interview with Rose and his final interview, also with Rose, just prior to his death only two years later. The first discussion offers evidence as to Judt’s role as a wise voice of reflection in an otherwise strident media environment. In that interview his powerful call for a renewed focus on the teaching of history is characteristically thoughtful and targeted as an antidote to the abuse of history by political leaders. The final interview, in which Rose struggles to check his grief over Judt’s condition, highlights the continued power of Judt’s mind even in his final days and as the toll of the disease was all too clear. As Rose notes, after his diagnosis and despite the debilitating impact of ALS, Judt wrote dozens of essays, two books, and – while wheelchair-bound and on a breathing apparatus – delivered a final public lecture at NYU to a packed auditorium.

Since discovering those first televised interviews, I’ve spent the better part of the past decade working my way through most of Judt’s published works. Postwar (a Pulitzer Prize finalist) is genuinely one of the few books that deserves the over-used dust jack endorsement of “magisterial”. The posthumously published Thinking the Twentieth Century continues Postwar’s analysis in a much more personalised way as a series of conversations with fellow historian Timothy Snyder.

Most recently, I delved into 2010’s Ill Fares the Land, the opening lines of which leave no doubt as to the author’s frame of mind as he entered the final months of his life:

“Something is profoundly wrong with the way we live today. For 30 years we have made a virtue out of the pursuit of material self-interest: indeed, this very pursuit now constitutes whatever remains of our sense of collective purpose. We know what things cost but have no idea what they are worth. We no longer ask of a judicial ruling or a legislative act: is it good? Is it fair? Is it just? Is it right? Will it help bring about a better society or a better world? Those used to be the political questions, even if they invited no easy answers. We must learn once again to pose them.”

The book is a pull-no-punches attack on materialism, demagoguery, and the perceived unwillingness of leaders to govern for the greater good. As one reviewer aptly noted, the book is “a dying man’s sense of a dying idea: the notion that the state can play a significant role in its citizens’ lives without imperiling their liberties”. While the work was criticised by some on the right for being less an analysis and more a jeremiad, many of its claims now seem prophetic, particularly his concern with growing inequality and class divisions.

Tony Judt’s singular ability to recognise underlying narratives and trends is sorely missed in an era of media rancour and glibness. His work, however, remains as timely as ever for that very reason. He focused not on the sound-bite but rather on providing readers (and listeners) genuine frameworks for understanding the contemporary world through a deep study of history. And, for those in Africa concerned with political transition or creeping authoritarianism, Judt’s reflections on postwar Eastern Europe’s journey from communism to EU ascension offers a road map of how transitional states and their leaders can navigate through immensely challenging times.

Judt’s premature death robbed the world of one of its foremost historians and a voice that would surely have helped make sense of our disordered present. Nevertheless, his body of work and his inimitable public persona still provide deeply relevant lessons. It would do us all a bit of good to remember those lessons and to remember Tony Judt. DM

Todd Johnson is the risk leader for a large multinational operating throughout Africa. He has also held roles in corporate strategy, political and partnership risk management, and in the US Government as an analyst of African politics.

Photo: British writer Tony Judt poses during the presentation of his essay ‘Postwar period. A History of Europe since 1945, in Madrid, Spain, Thursday 26 October 2006. EPA/VICTOR LERENA